Basic Neurophysiology and Neuroanatomy

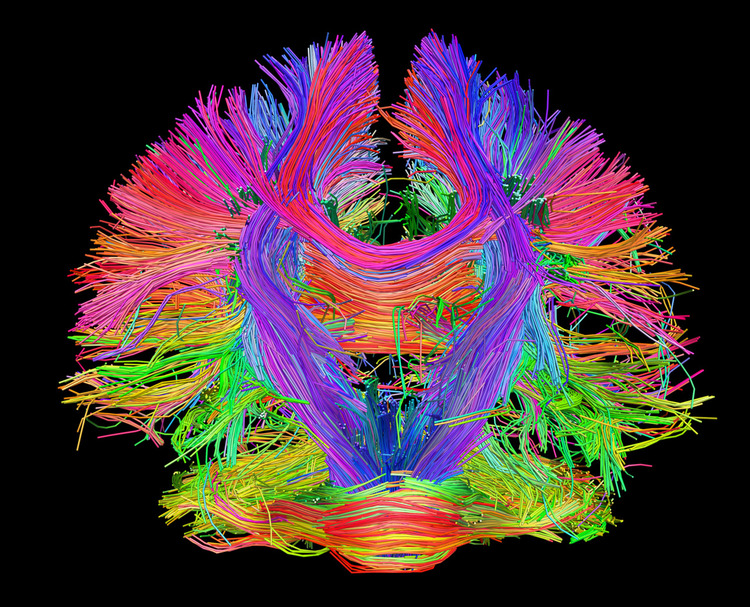

The brain uses a sophisticated communication and command-and-control system that monitors and manages interactions between roughly 100 billion neurons, each with 5,000-10,000 synaptic connections, for as many as 500 trillion synapses in adults (Breedlove & Watson, 2020).

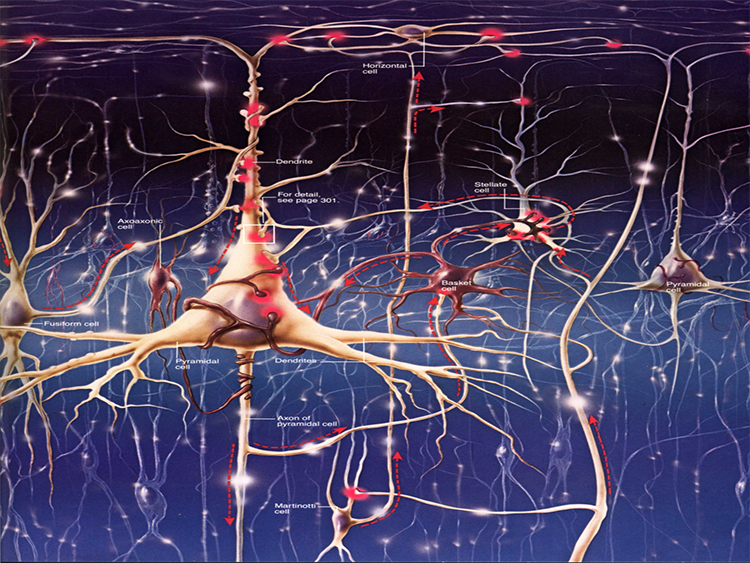

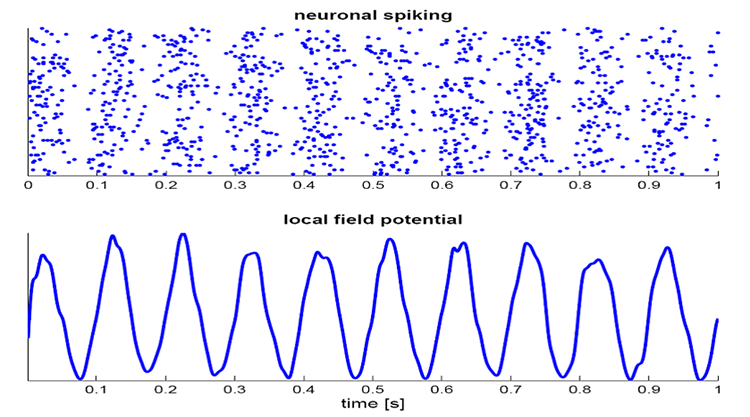

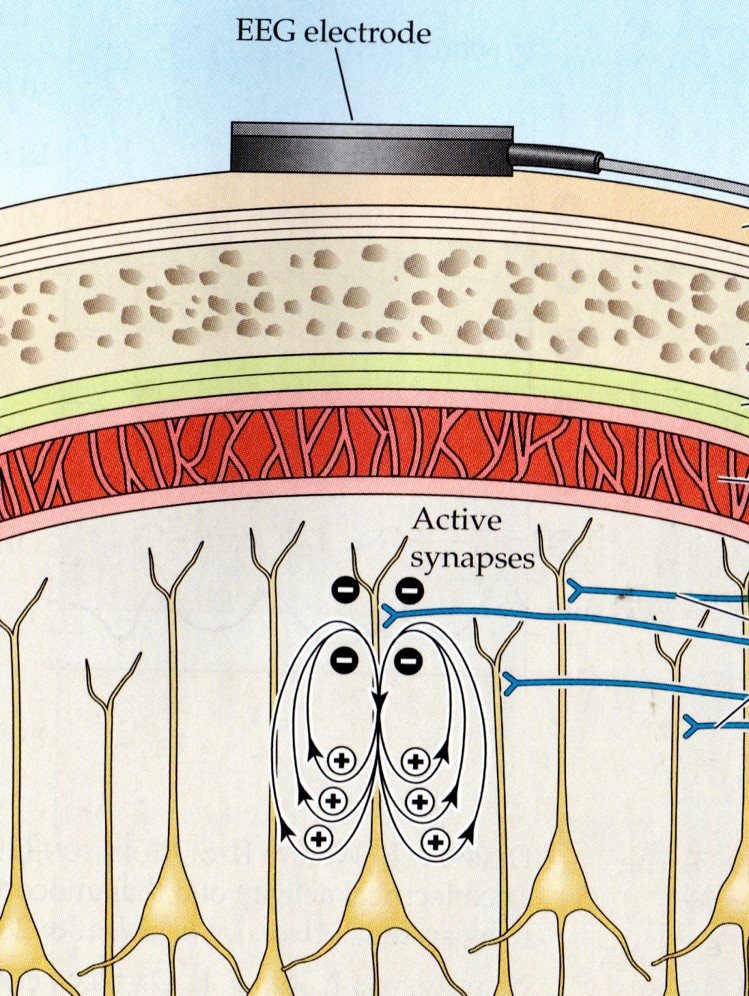

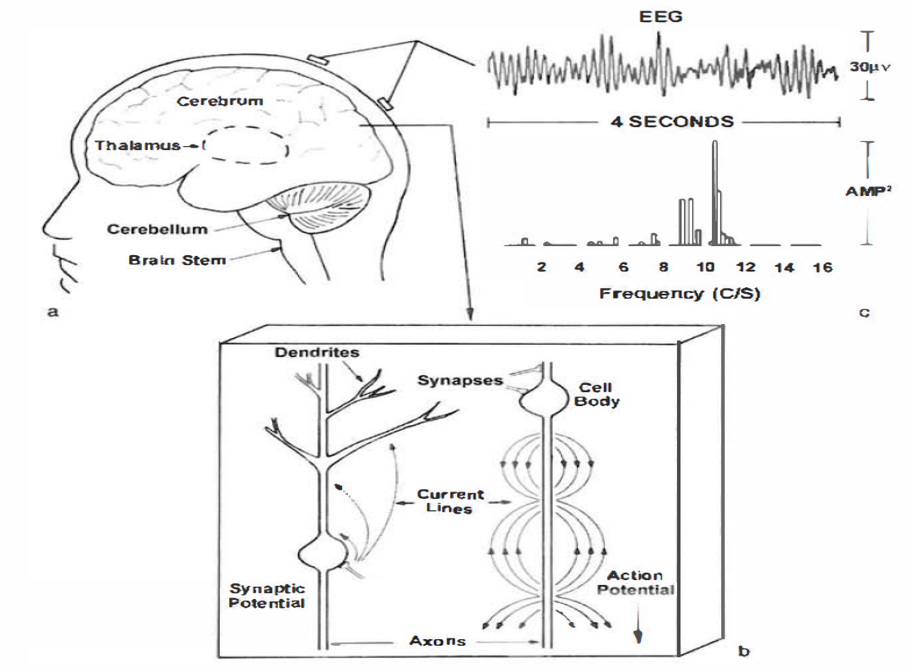

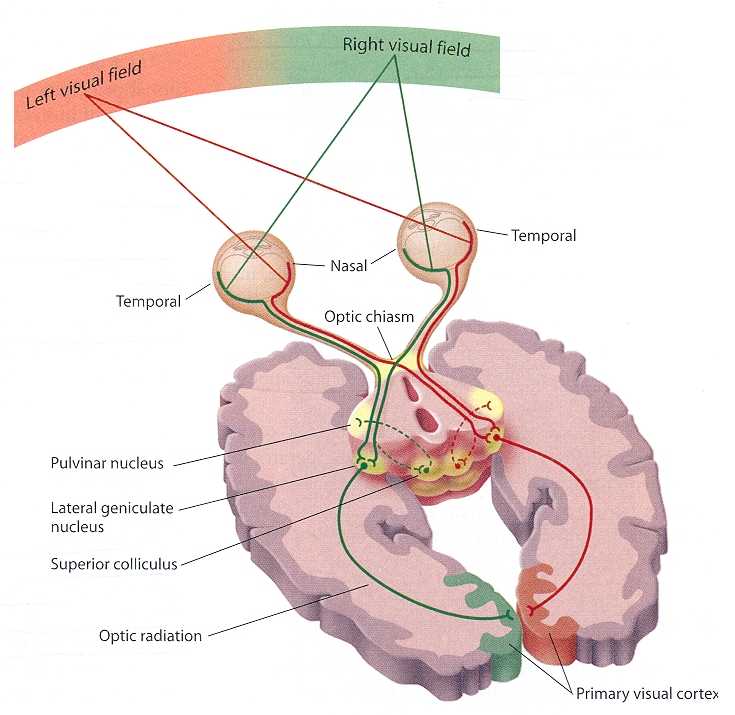

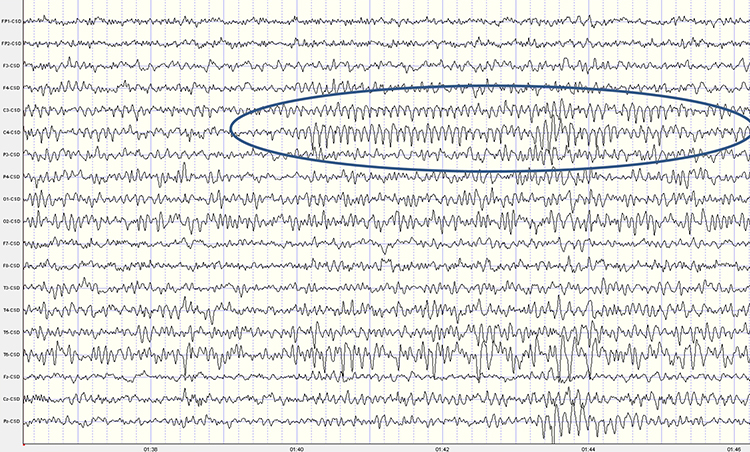

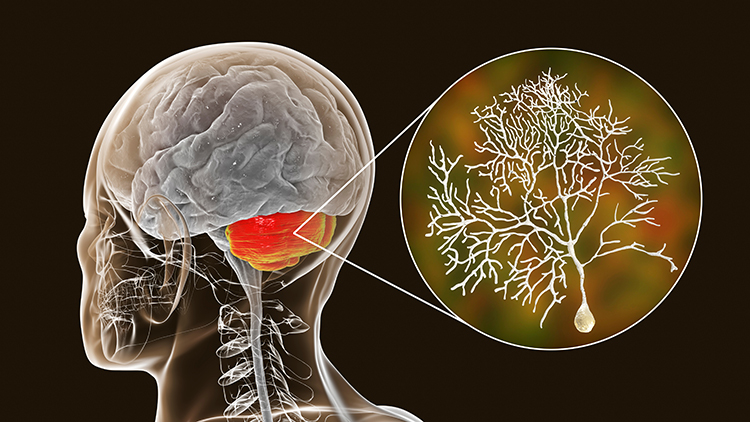

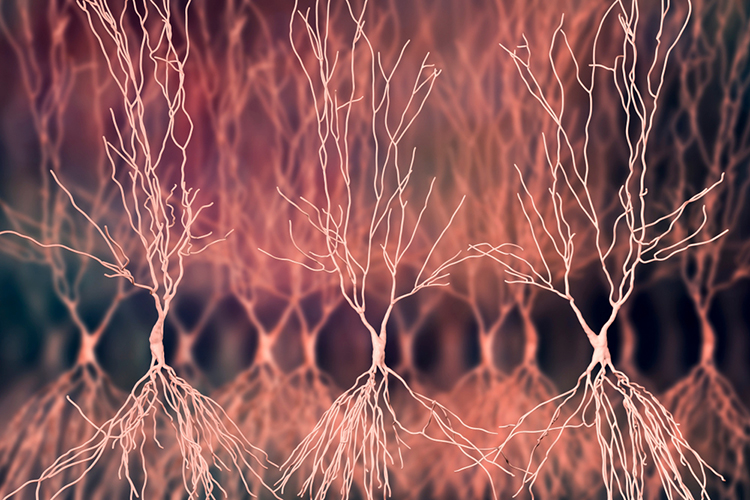

An electroencephalograph (EEG) monitors brainwave activity at various frequencies, from DC shifts (slow cortical potentials) to fast potentials exceeding 50 Hz. The EEG records the excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) and inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs) propagated by the apical dendrites of large pyramidal cells arranged in thousands of cortical columns. Local field potentials, the aggregate effect of interconnected neuron firing and modulation by glial cells, regulate neuron excitability and firing. Action potential animation © NIMEDIA/Shutterstock.com.

Neuroplasticity, the remodeling of neurons and neural networks with experience, is responsible for learning and memory and makes neurofeedback training possible.

MCP Blueprint Coverage

This unit addresses II. Basic Neurophysiology and Neuroanatomy.

A. NEUROPHYSIOLOGY

This unit covers the Bioelectric Origin and Functional Correlates of EEG, Definition of ERPs and SCPs, and Neuroplasticity.

Bioelectric Origin and Functional Correlates of EEG

Types of Neurons

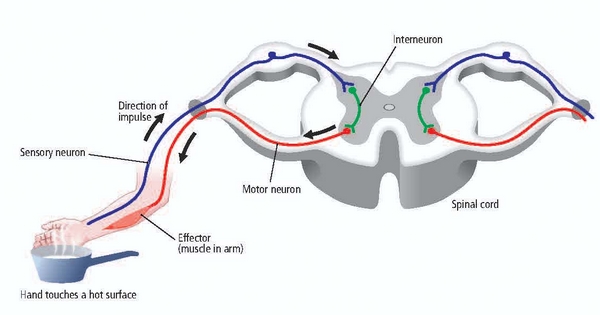

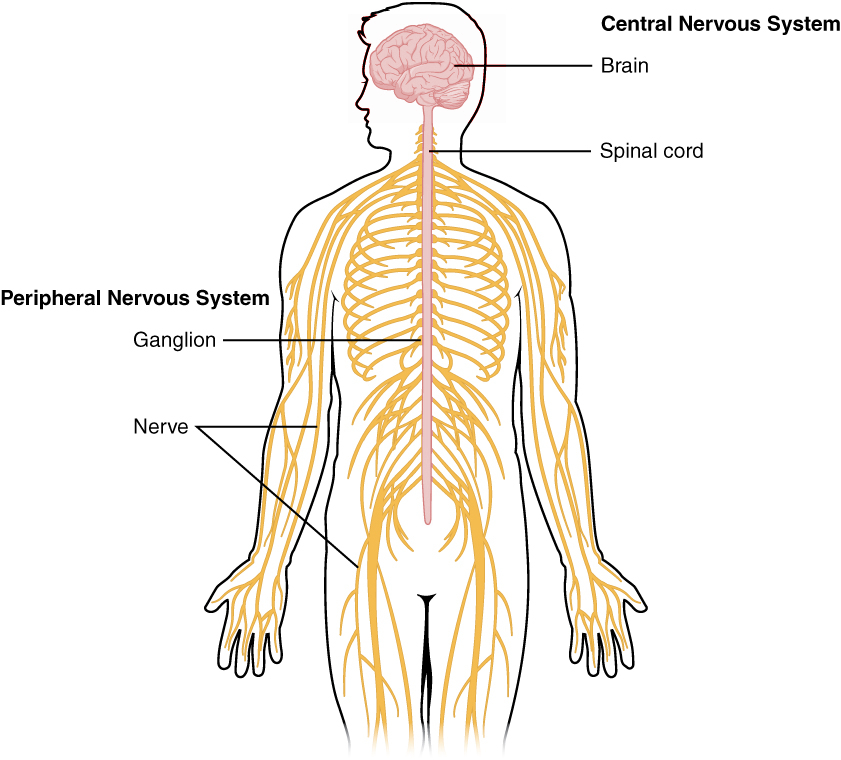

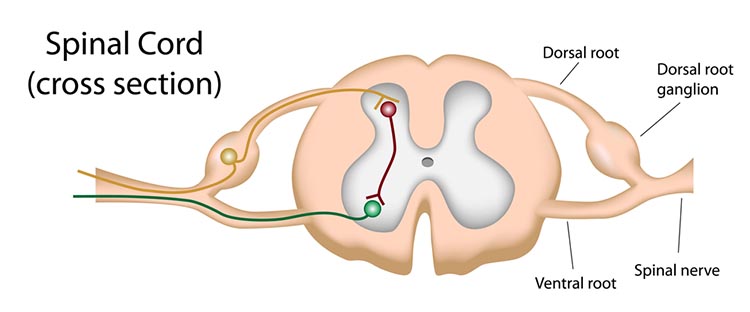

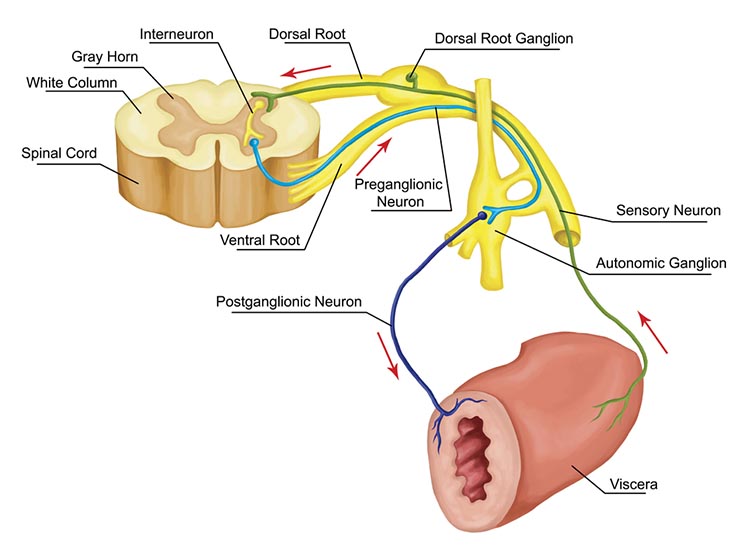

Sensory neurons are specialized for sensory intake. They are called afferent because they transmit sensory information towards the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord). The graphic below is courtesy of leavingcertbiology.net.

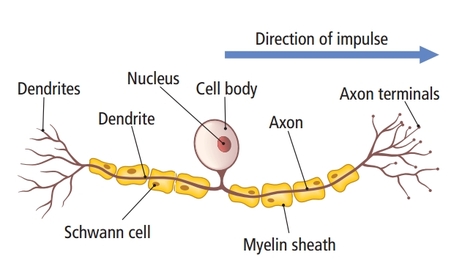

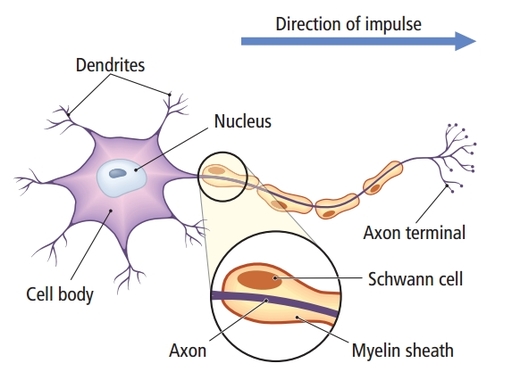

Motor neurons convey commands to glands, muscles, and other neurons. They are called efferent because they convey information towards the periphery. Graphic courtesy of leavingcertbiology.net.

Interneurons provide the integration required for decisions, learning and memory, perception, planning, and movement. They have short processes, analyze incoming information, and distribute their analysis with other neurons in their network. Interneurons are entirely confined to the central nervous system, account for many of its neurons, and comprise most of the brain (Breedlove & Watson, 2020). Local interneurons analyze small amounts of information provided by neighboring neurons. Relay interneurons connect networks of local interneurons from separate regions to enable diverse functions like perception, learning, and memory, and executive functions like planning (Carlson & Birkett, 2021). Graphic courtesy of leavingcertbiology.net.

Neuron Structure

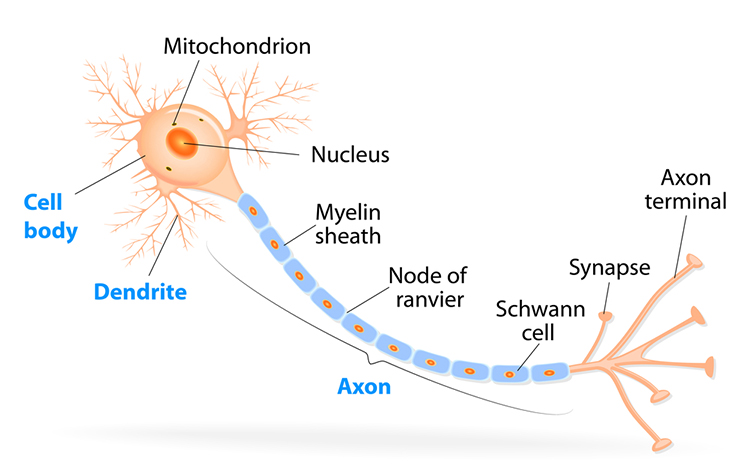

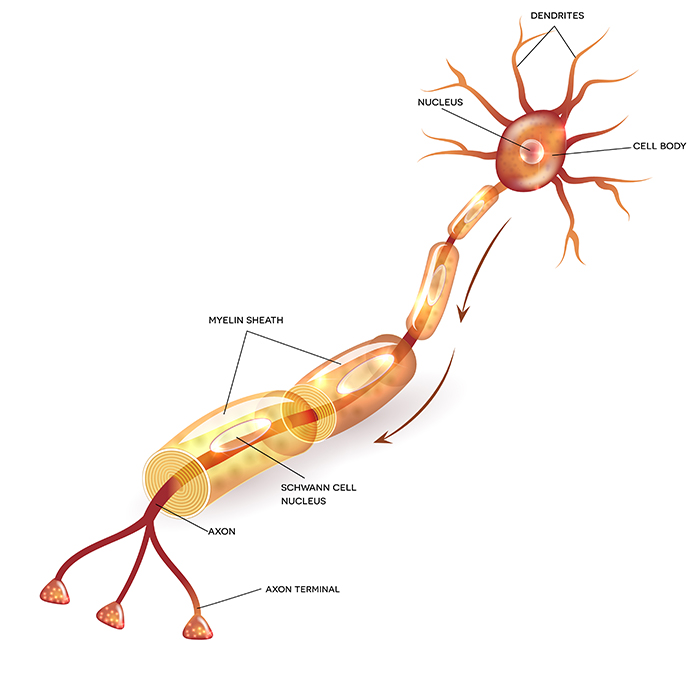

While neurons have over 200 different designs to perform specialized jobs in the nervous system, they generally have five structures: a cell body or soma, dendrites, an axon and axon hillock, and terminal buttons. Check out the Blausen Neuron Structure in CNS animation. Graphic © Designua/Shutterstock.com.

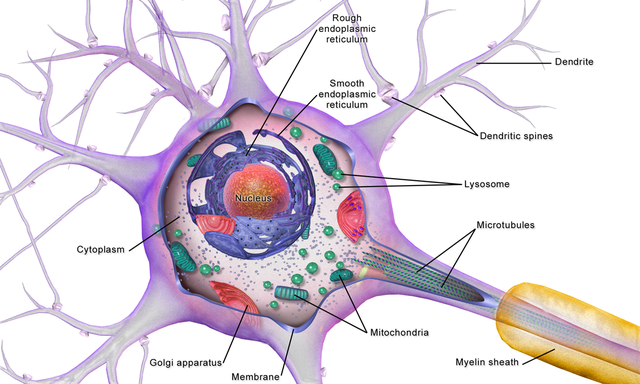

The

cell body or soma contains the machinery for the neuron’s

life processes. It receives and integrates EPSPs and IPSPs, small graded positive and negative changes in

membrane potential generated by axons. The cell body of a typical neuron is

20 μm in diameter, and its spherical nucleus,

which contains chromosomes comprised of DNA, is 5-10

μm across. The cell body is the only location where neurons manufacture proteins (like enzymes,

receptors, and ion channels) and peptides (neurotransmitters like oxytocin) since this requires ribosomes. Check out the Khan Academy YouTube video, Anatomy of a Neuron.

Dendrites are branched structures designed to receive messages from other neurons via axodendritic synapses (junctions between axons and dendrites shown below) and send messages to other neurons dendrodendritic synapses (junctions between the dendrites of two neurons). Dendrites receive thousands of synaptic contacts and have specialized proteins called receptors for neurotransmitters released into the synaptic cleft (Bear, Connors, & Paradiso, 2020).

A neuron's dendrites are called a dendritic tree, and each branch of the tree is called a dendritic branch. Graphic by BruceBlaus from Wikipedia article Neuron.

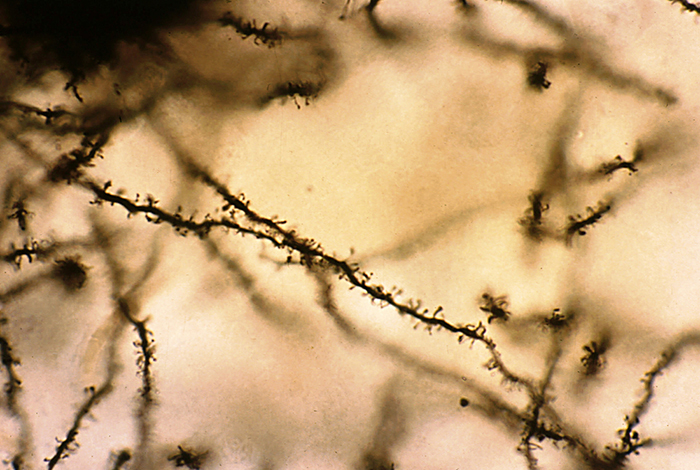

Biological psychologists classify neurons based on whether their dendrites feature spines. Dendritic spines are protrusions on the dendrite shaft where axons

typically form axodendritic synapses. Graphic © Jose Luis Calvo/Shutterstock.com.

Spiny neurons have dendritic spines, while aspinous neurons do not (Bear, Connors, & Paradiso, 2020).

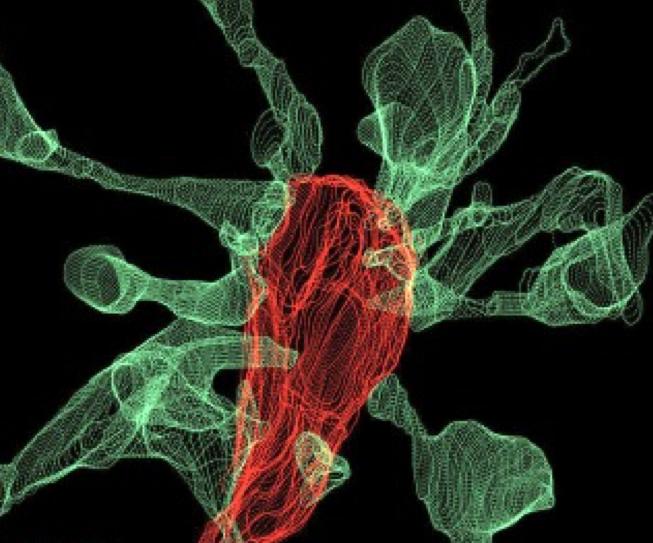

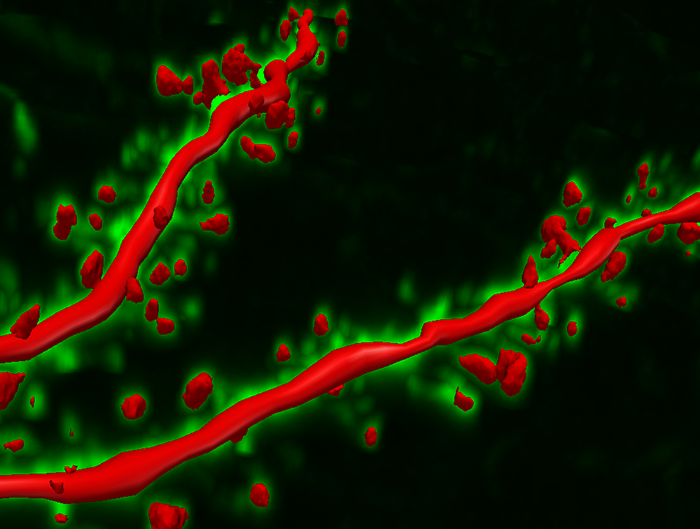

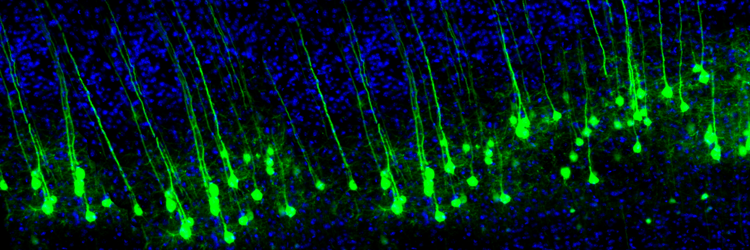

During learning, spines' number, size, and shape may change to adjust the space for receptors (neuroplasticity). Microglia shown in green participate in the remodeling process. Graphic © Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News.

An axon is a cylindrical structure only found in neurons that is specialized for the distribution of information within the central and peripheral nervous systems. Axons range from 1 to 25 µm in diameter and 0.1 mm to more than a meter in

length. Over 90% of neurons are interneurons whose axons and dendrites are very short and do not

extend beyond their cell cluster. Axons usually branch repeatedly. Each branch is called an axon collateral.

Axons transmit

action potentials

toward a neuron's terminal buttons. Using microtubules, an axon also bidirectionally transports molecules between the cell body and terminal buttons.

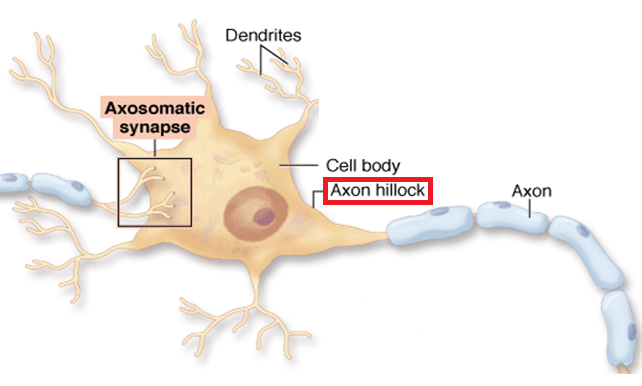

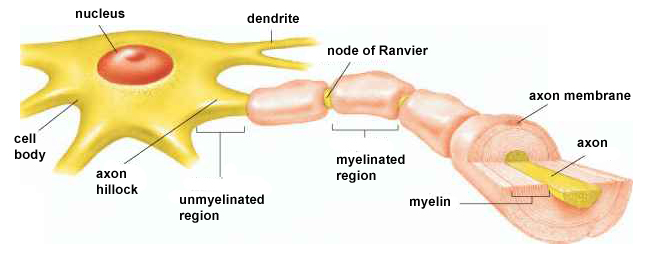

An axon hillock is a swelling of the cell body where the axon

begins. The middle of an axon is the axon proper, and the end is the axon terminal (Bear, Connors, & Paradiso, 2020). Graphic by M.alijar3i from the Wikipedia article Axon Hillock.

The axon hillock sums EPSPs and IPSPs over milliseconds to generate an action potential.

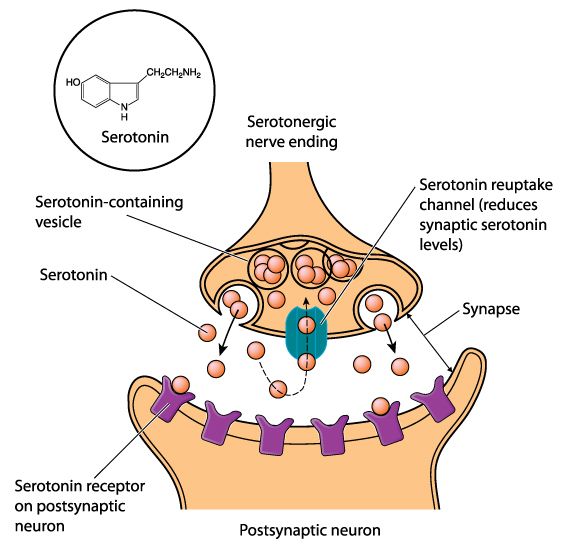

Axon terminals are buds located on the ends of axon branches

that form synapses and release neurochemicals to other neurons. Axon terminals contain vesicles that store

neurotransmitters for release when an action potential arrives. Their presynaptic membrane

may have reuptake transporters that return neurotransmitters from the synapse or extracellular space for

repackaging. The graphic of serotonin reuptake transporters below is courtesy of NIDA.

Types of Glial Cells

While there are hundreds of types of neurons, there are only four main categories of glial cells (astrocytes, microglia, oligodendrocytes, and Schwann cells).Old school view: glial cells mainly provide structural support (glia is derived from the Greek for glue).

New school view: glial cells help neurons process information, including modulating neuron excitability.

Check out the YouTube video, Neurology - Glial Cells, White Matter and Gray Matter.

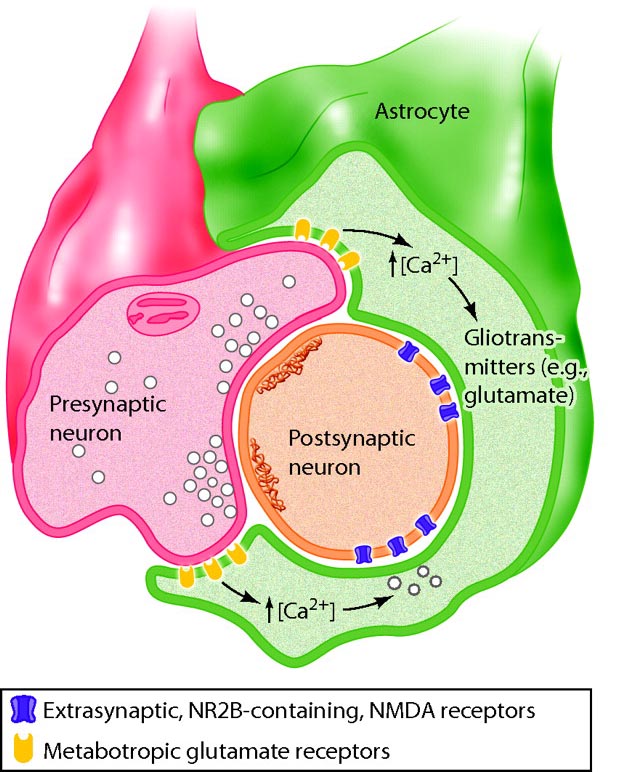

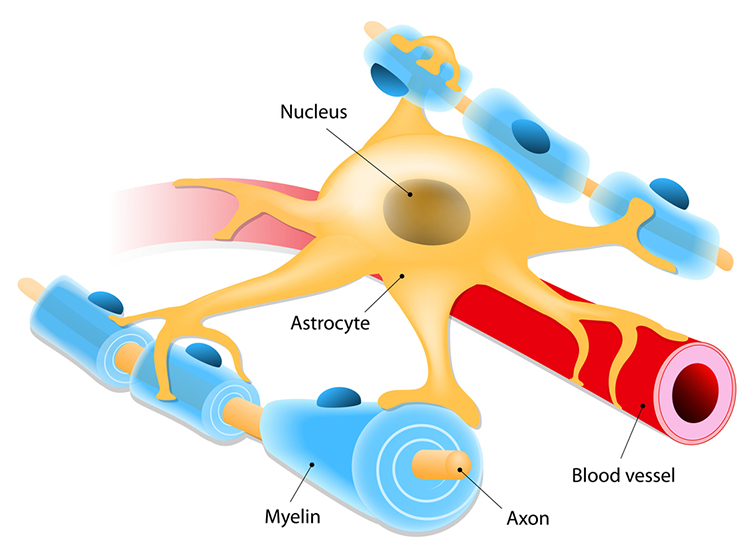

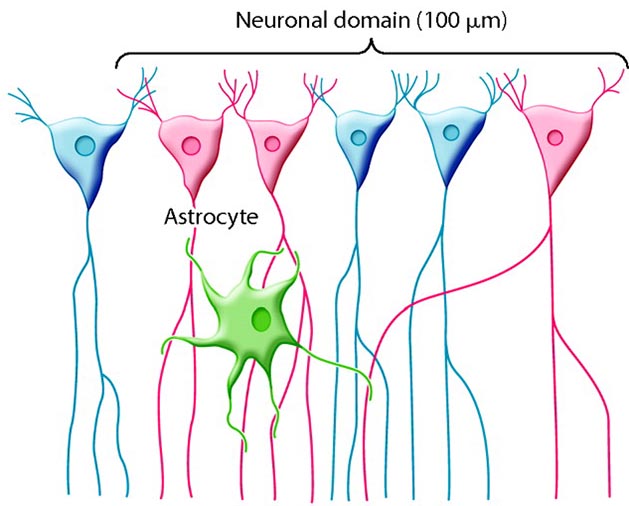

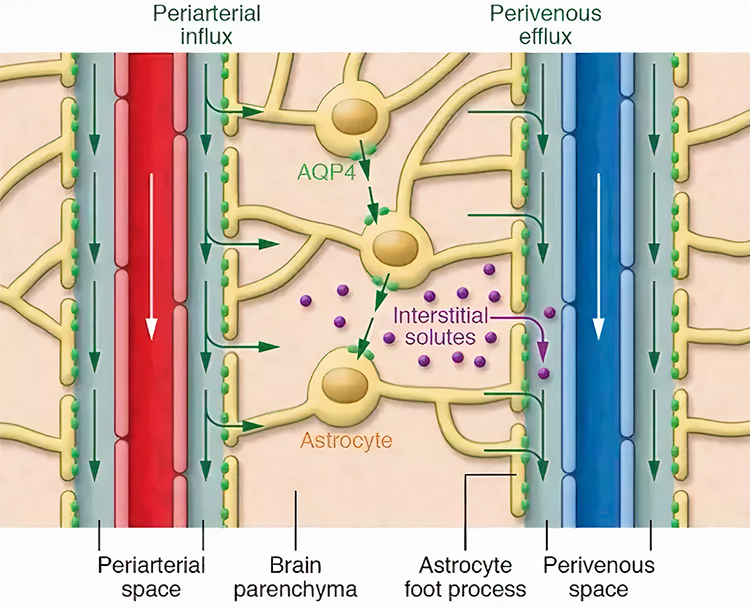

Astrocytes (shown below) are star-shaped and are the most prevalent glial cells in the brain. They guide neuronal migration in the embryo and fetus. Since they occupy most of the expanse between neurons and are separated from neurons by nearly 20 µm, they may affect the growth or retraction of axons and dendrites (collectively called neurites). An emerging view is that astrocytes help neurons process information and communicate with each other through parallel astrocyte-astrocyte networks. Astrocyte membranes contain neurotransmitter receptors that can initiate changes in their membrane potential and internal biochemical processes.

Astrocytes regulate circulating molecules in the extracellular space (the region surrounding neurons) and the synapse. They enclose synapses, limit the movement of released neurotransmitters, and transport them from the synapse to the axon terminal. They also regulate the concentration of ions like potassium outside of neurons to prevent interference with their performance (Bear, Connors, & Paradiso, 2020).

Astrocytes transport nutrients, remove wastes, store glycogen during stage-3 sleep, dynamically control local blood flow, and develop and maintain the blood-brain barrier.

Astrocytes develop and maintain

the blood-brain barrier. Graphic © Designua/Shutterstock.com.

Astrocytes directly receive synapses from neurons and integrate neuronal messages, monitor the activity of

nearby synapses, communicate with each other using calcium ions and ATP, converse with nearby neurons using

neurotransmitters, and strongly influence the number of synapses. Schwann cells help determine synapse location.

Graphic © 2016 physiologyonline.physiology.org.

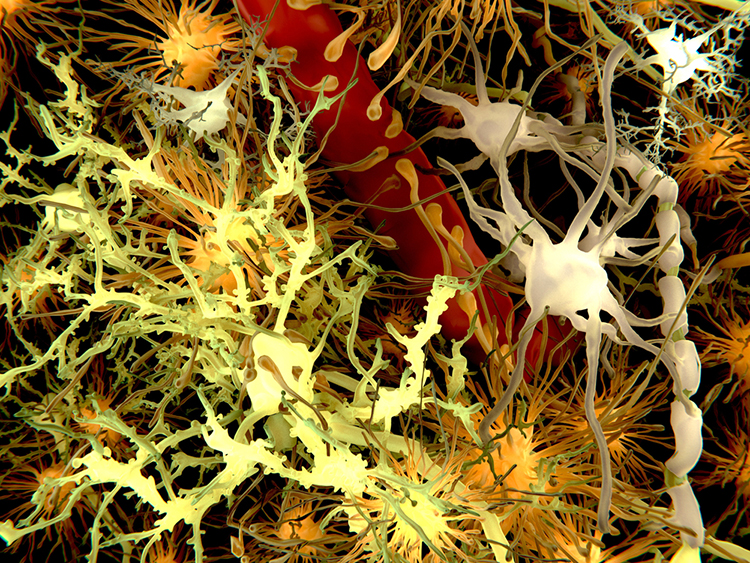

Microscopic microglial cells participate in the immune

response. Microglial cells scavenge and engulf diverse materials (phagocytosis), release cytotoxins to control infection,

present antigens to T-cells, remove branches from neurons near damaged tissue to aid regrowth (synaptic

stripping), promote tissue repair, and promote chronic neuroinflammation in the CNS that amplifies

neurodegeneration. They assist synaptic remodeling by removing unnecessary synapses. Finally, microglia cross the blood-brain barrier to promote homeostasis (Bear, Connors, & Paradiso, 2020). Graphic © Juan Gaertner/Shutterstock.com.

Description: yellow = neurons, orange = astrocytes, grey = oligodendrocytes, white = microglia.

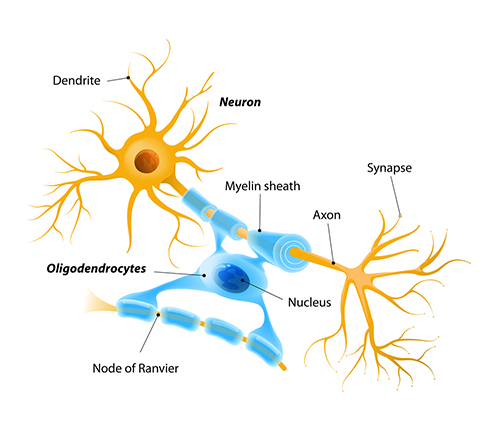

Oligodendrocytes, which are smaller than astrocytes, form up to 50

segments of myelin that only insulate adjacent axons within the brain and spinal cord of the central nervous system. Check out the Blausen Neural Tissue: Oligodendrocyte animation. Graphic © Designua/Shutterstock.com.

Oligodendrocytes block axonal regeneration by releasing growth inhibitory proteins. These molecules are part of the reason

for minimal functional recovery in the CNS following spinal cord damage. Multiple

sclerosis, a demyelinating disease, destroys oligodendrocytes.

Check out the Blausen Demyelination in the CNS: Multiple Sclerosis animation.

Schwann cells provide myelin for single PNS axons and facilitate

axonal regeneration following damage (Breedlove & Watson, 2020). Check out the Blausen Neuroglia: Schwann Cell on Myelinated Peripheral Neuron animation.

Graphic © Tefi/Shutterstock.com.

Excitatory and Inhibitory Postsynaptic Potentials

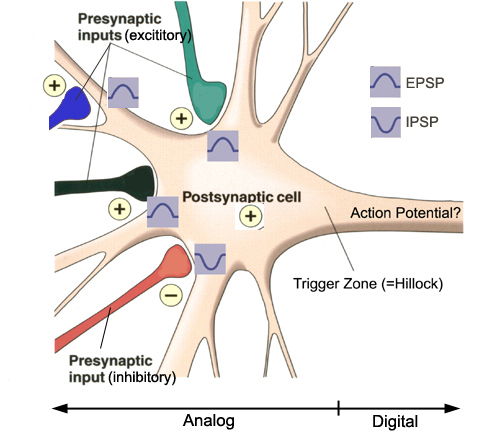

Graded positive and negative changes in membrane potential, called excitatory postsynaptic potentials and inhibitory postsynaptic potentials, are essential to the EEG and communication among neurons.An excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) is a subthreshold depolarization that makes the membrane potential more positive and pushes the neuron towards its excitation threshold. EPSPs are produced when neurotransmitters bind to receptors and cause positive sodium ions to enter the cell. At a single synapse, a postsynaptic membrane may have tens to thousands of transmitter-gated ion channels. The amount of transmitter released determines how many of these channels will be activated. The size of an EPSP will be a multiple of the number of vesicles, each containing several thousand transmitter molecules. Check out the Blausen Positive Potential animation.

An inhibitory postsynaptic potential (IPSP) is a hyperpolarization that makes the membrane potential more negative and pushes the neuron away from its excitation threshold. At most inhibitory synapses, IPSPs are produced when neurotransmitters like GABA or glycine bind to receptors and cause negative chloride ions to enter the cell. When an inhibitory synapse is closer to the soma than an excitatory synapse, it can counteract positive current flow and decrease the size of the EPSP. This mechanism is called shunting inhibition (Bear, Connors, & Paradiso, 2020).

Integrating Postsynaptic Potentials

Integration is the summation of EPSPs and IPSPs at the unmyelinated axon hillock.

The axon hillock of a postsynaptic neuron uses two methods to sum EPSPs and IPSPs: spatial and temporal summation.

In spatial summation, the axon hillock sums the simultaneous postsynaptic potentials (PSPs) from thousands of synapses on dendrites. In temporal summation, the axon hillock adds the PSPs from presynaptic neurons that repeatedly fire within a 1-15-ms time window.

Each EPSP depolarizes the axon hillock by about 0.5 mV. If there were no competing IPSPs, it would take about 30 EPSPs to trigger an action potential. Each IPSP hyperpolarizes the axon hillock by about 0.5 mV. If the summated EPSPs and IPSPs move the axon hillock from a resting potential of -70 mV to a threshold of excitation of -55 mV, sodium channels in the axon hillock membrane open, and an action potential propagates down the axon. Graphic © 2003 Josephine Wilson.

Check out the YouTube video, Best Action Potential Explanation.

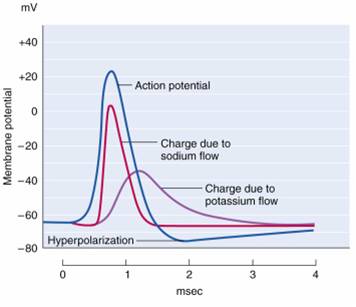

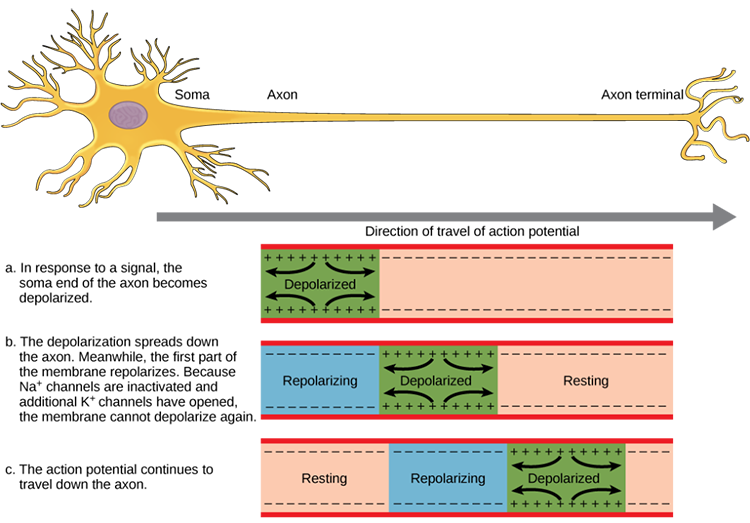

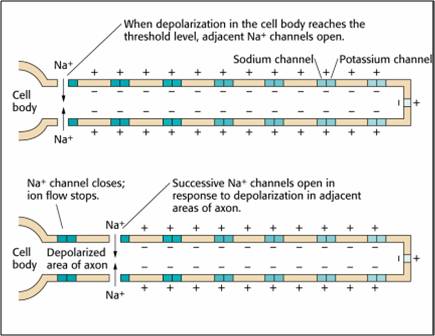

Action Potentials

An action potential is a brief electrical impulse that transmits information from the axon hillock to the terminal button. This wave of positive charge only travels in one direction because the preceding segment is refractory due to the closing of its sodium channels. An action potential takes 1-2 ms from the point the axon hillock reaches its threshold to its repolarization to a negative resting potential.Watch the Blausen Action Potential animation.

Action potentials travel down axons, which branch multiple times and terminate at synapses. The all-or-none law and rate laws describe action potential transmission. The all-or-none law states that once an action potential is triggered in an axon, it is propagated, without decrement, to the end of the axon. The rate law states that neurons represent the intensity of a stimulus by variation in the rate of axon firing. More intense stimuli shorten the interval before a neuron can fire again, allowing a neuron to fire more rapidly. An intense stimulus can cause a neuron to fire every 2 or 3 ms, while a weak stimulus might lengthen the time lag to every 4 or 5 ms.

We can compare action potential conduction to the movement of water through a leaky garden hose.

Garden hose: water can take two paths, inside the hose or through holes in its wall, and the majority of the water will flow where movement is easiest. For a small-diameter hose with many large holes, most of the water will travel through the leaks. Conversely, for a large-diameter hose with only a few small holes, the bulk of the water will remain inside.

Axon: positive charge can take two paths, inside the axon or through pores in its membrane. Like water, a positive charge will take the path of least resistance. For a small-diameter axon with many open sodium ion channels, the majority of the current will exit the axonal membrane to the extracellular fluid. Small diameter, unmyelinated axons transmit action potentials without weakening since sodium ion channels constantly regenerate this signal. This method is slow because the signal travels step-by-step, small segment by small segment, and waits for sodium channels to admit enough positive ions to reach the excitation threshold. Check out the Blausen Continuous and Saltatory Propagation animation. Graphic © 2003 Josephine Wilson.

This method also consumes considerable energy since sodium-potassium transporters, powered by ATP, are located across the axon membrane to exchange three sodium for two potassium ions.

Conversely, for a large-diameter axon with few open ion channels, the bulk of the current will remain inside the axon's interior. Wider spacing between adjacent ion channels means that the action potential can depolarize a longer axon segment, which increases conduction velocity (Bear, Connors, & Paradiso, 2020).

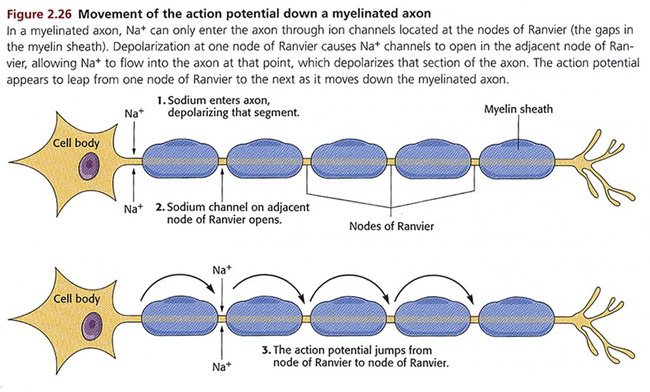

Medium-to-large diameter myelinated axons transmit action potentials using a method called saltatory conduction. Each segment of insulating myelin is almost 1-mm long. The gaps between segments, called nodes of Ranvier, are 1 to 2 thousandths of a millimeter. An action potential weakens under each myelinated segment (cable properties) and is then regenerated at each Ranvier node. The destruction of this insulation by demyelinating diseases like multiple sclerosis (MS) can be devastating because it disrupts neuron-to-neuron communication.

Saltatory conduction can be 200 times faster because the action potential jumps from node to node, in 1-mm steps,” instead of steps that are a thousand times smaller. This method is also more energy-efficient because sodium-potassium transporters are only needed at the nodes of Ranvier, where ion exchange is possible. These transporters account for about 40% of a neuron’s energy expenditure (Breedlove & Watson, 2020; Garrett, 2003). Graphic © 2003 Josephine Wilson.

Communication Between Neurons

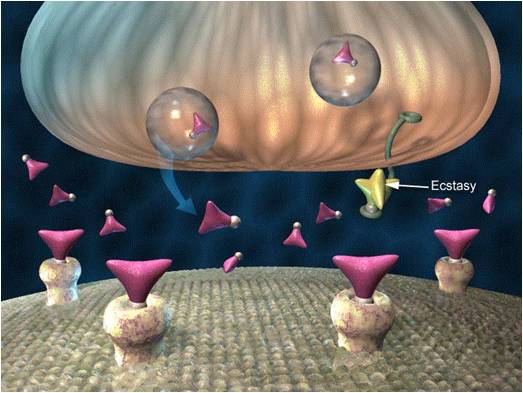

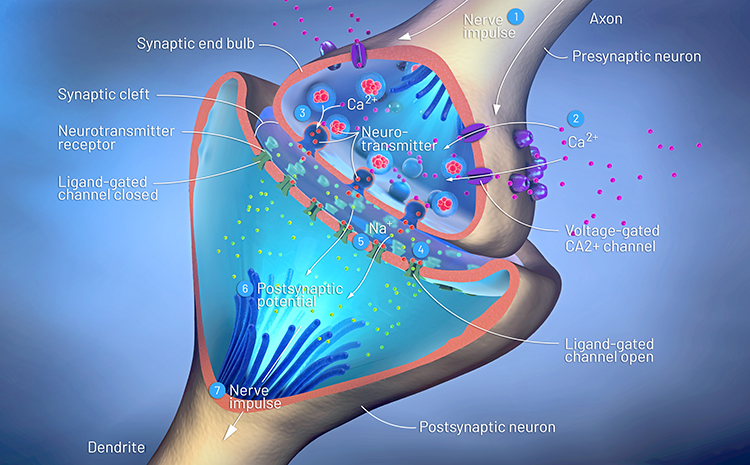

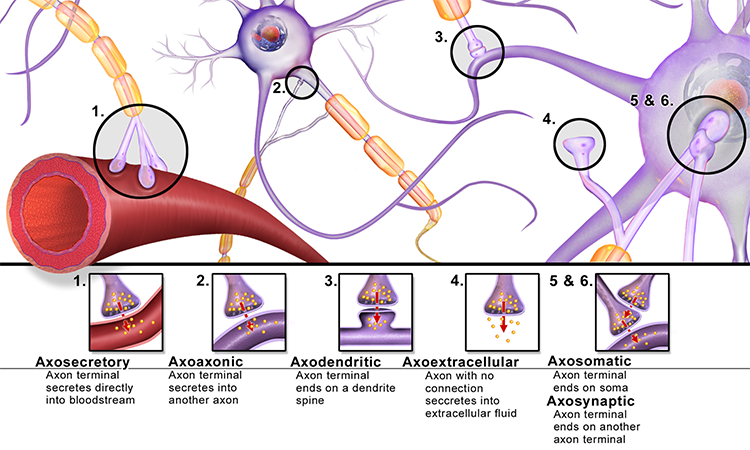

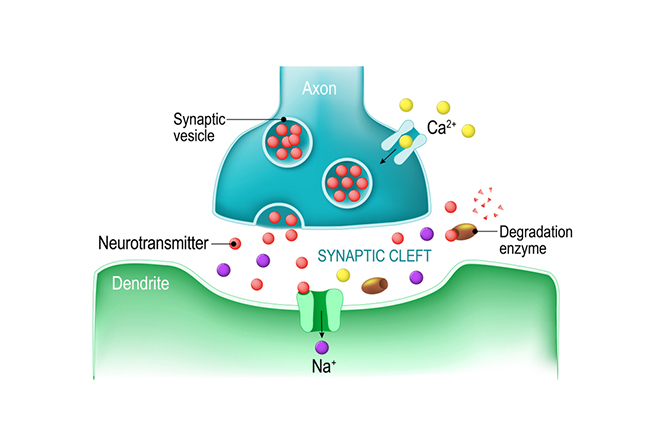

Neurons communicate through the release of neurochemicals and ions. Axon terminal buttons release neurochemicals across a 20-40-nm fluid-filled gap between presynaptic and postsynaptic structures called a synaptic cleft and into the extracellular fluid surrounding the neuron. Chemical synapses produce short-duration (millisecond) and long-duration (seconds to days) changes in the nervous system. Check out the YouTube videos, Neurotransmitter Synapse 3D animation and Neuronal Synapses.They are functionally asymmetrical because the presynaptic neuron sends a chemical message and the postsynaptic neuron receives it. They are structurally asymmetrical because the presynaptic element (axon) contains vesicles containing neurotransmitters, and the postsynaptic element (dendrite) doesn’t. The release of neurochemicals when an action potential arrives at the terminal button is called exocytosis. Graphic © Christoph Burgstedt/Shutterstock.com.

Old-school view: according to Dale’s law, a neuron can only release one neurotransmitter at a synapse.

New-school view: neurons can release a classical neurotransmitter and a peptide.

Old-school view: axon terminals only release neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft.

New-school view: Neurotransmitter release also occurs outside of the synaptic cleft. Axonal varicosities (swellings in axon walls), dendrites, and the terminal button can release transmitters into the extracellular space. Graphic © 3Dme Creative Studio/Shutterstock.com.

Neuromodulation via Axoaxonic Synapses

Axons can influence the amount of neurotransmitters released when an action potential arrives at an axon terminal through axoaxonic synapses (junctions between two axons). Graphic © BruceBlaus.

Axoaxonic synapses do not affect the generation of an action potential, only the amount of neurotransmitter distributed. In presynaptic facilitation, a neuron increases the presynaptic neuron's neurotransmitter release by delivering a neurotransmitter that increases calcium ion entry into its terminal button. In presynaptic inhibition, a neuron decreases neurotransmitter release by reducing calcium ion entry. These modulatory effects are confined to a single synapse (Breedlove & Watson, 2020).

Types of Neurotransmitters

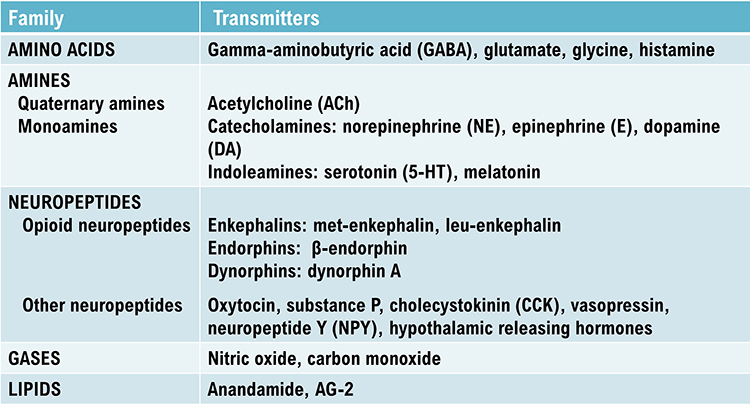

While the actual number of neurotransmitters is not known, more than 200 molecules have been identified. Each neurotransmitter may have multiple receptors. A neurotransmitter's effect, excitatory or inhibitory, depends on its interaction with specific receptors. The same neurotransmitter can produce opposite results at different receptor subtypes (Breedlove & Watson, 2020).The principal neurotransmitter families include amino acid neurotransmitters (GABA, glutamate), amine neurotransmitters (acetylcholine, dopamine serotonin), peptide neurotransmitters, also called neuropeptides (oxytocin, vasopressin), gas neurotransmitters (nitric oxide, carbon dioxide), and lipid neurotransmitters (anandamide and AG-2). The table below is adapted from Breedlove and Watson (2020).

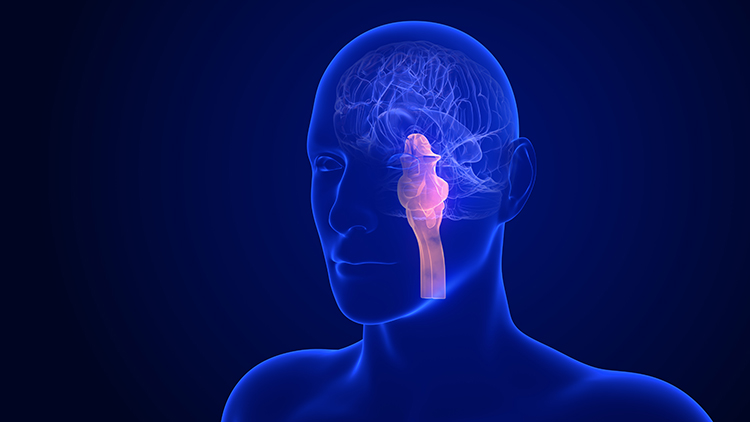

Neurotransmitter Pathways

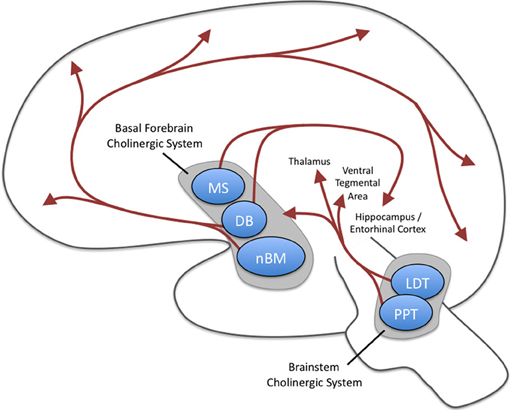

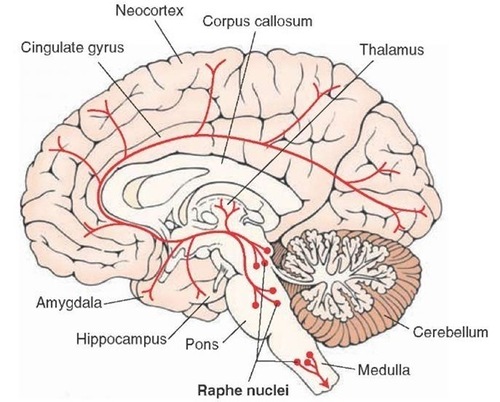

Researchers have identified pathways for acetylcholine, dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin. The reproduced diagrams are © Vasilisa Tsoy/Shutterstock.com.Cholinergic pathways

.jpg)

Cholinergic cell bodies and their projections originate in the basal forebrain and brainstem. Cholinergic pathways are involved in arousal, attention, memory, motivation, muscle contraction, and sleep. Watch the Blausen Chemical Synapse: Cholinergic Synapse animation.

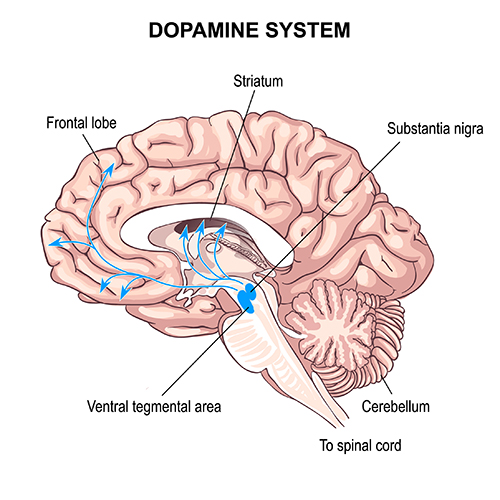

Dopaminergic pathways

Two major dopaminergic pathways originate in the midbrain: the mesostriatal and mesolimbocortical pathways. Dopaminergic pathways are involved in addiction, motor control, and salience (reward- and threat-based motivation). Check out the Blausen Parkinsons Disease animation.

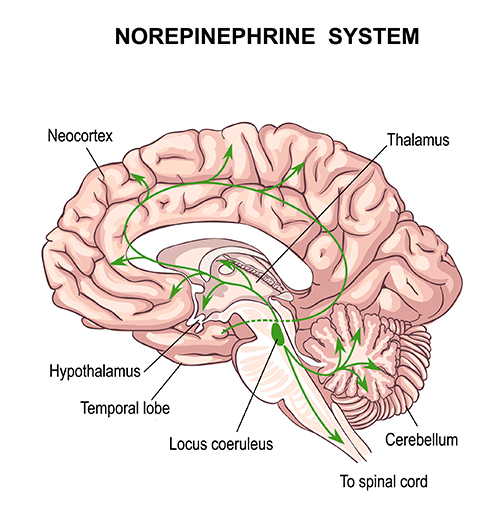

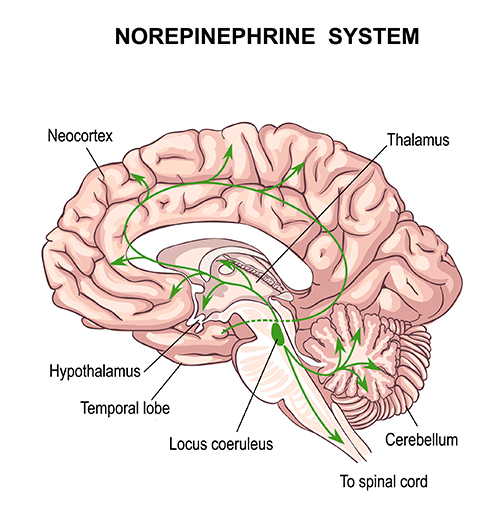

Noradrenergic pathways

The noradrenergic pathways originate in the midbrain locus coeruleus and lateral tegmental area. Noradrenergic pathways are involved in arousal, attention, memory, vigilance, sleep, and mobilizing the brain and body for action, including the fight-or-flight response.

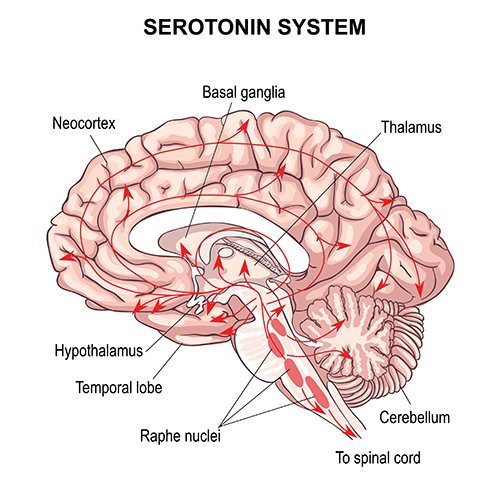

Serotonergic pathways

The serotonergic pathways originate in the brainstem and midbrain raphe nuclei. Serotonergic pathways are involved in appetite, mood, and sleep.

Termination of Neurotransmitter Action

Following exocytosis, neurotransmitter action is terminated by reuptake and enzymatic degradation. In reuptake, reuptake transporters located in the presynaptic terminal and astrocytes that enclose the synapse return neurotransmitter molecules to the presynaptic neuron. Astrocytes remove glutamate from the synapse. Graphic © Blamb/Shutterstock.com.

In enzymatic degradation, enzymes located in the synaptic cleft and the cytoplasm of the presynaptic neuron's terminal button split neurotransmitter molecules apart (e.g., acetylcholine). Graphic © Designua/Shutterstock.com.

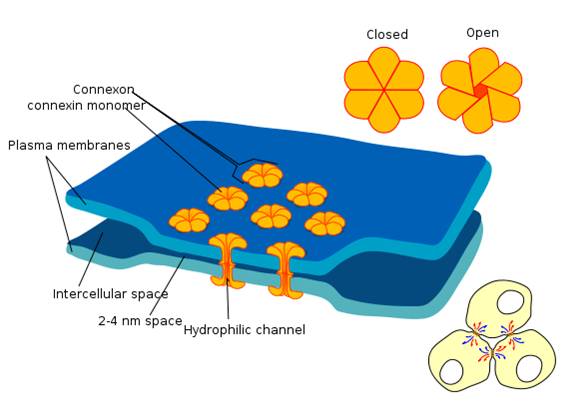

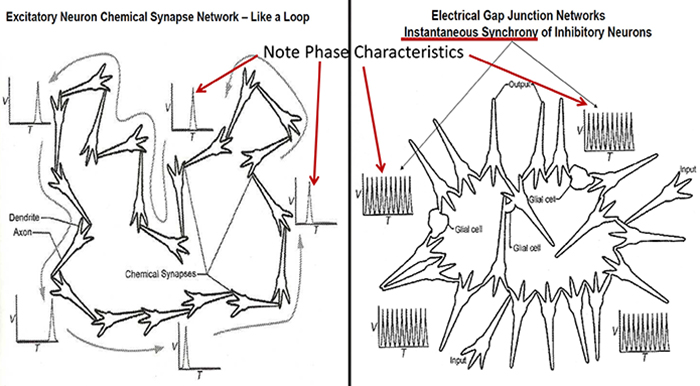

Electrical Synapses

Electrical synapses communicate information across gap junctions between adjacent membranes using ions. Gap junctions are narrow spaces between two cells bridged by connexons (protein channels) that allow ions near-instantaneous travel. Graphic courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

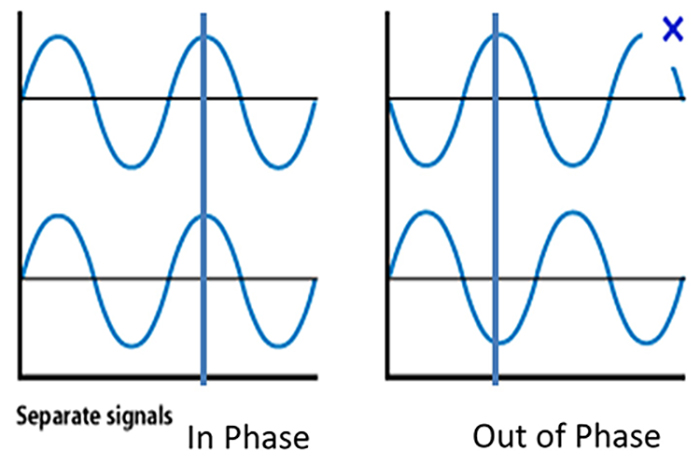

Electrical synapses are symmetrical. Ions flow across a 3-nm gap junction into the more negatively charged neuron as long as the gap junction remains open. This means that whether neurons are presynaptic or postsynaptic depends on their respective charges. When two neurons are electrically coupled, an action potential in one induces a postsynaptic potential (PSP) in the paired neuron.

Transmission across electrical synapses is instantaneous, compared with the 10-ms or longer delay in chemical synapses. The rapid information transmission that characterizes electrical synapses enables large circuits of neurons to synchronize their activity and simultaneously fire.

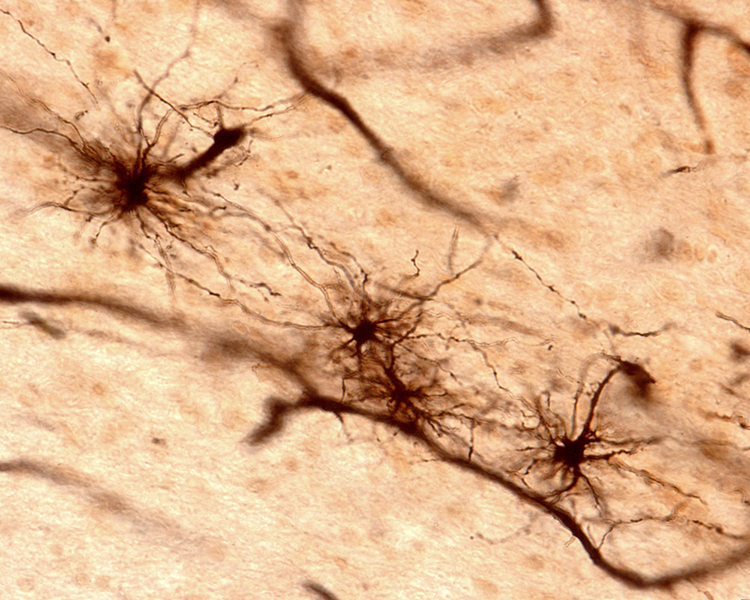

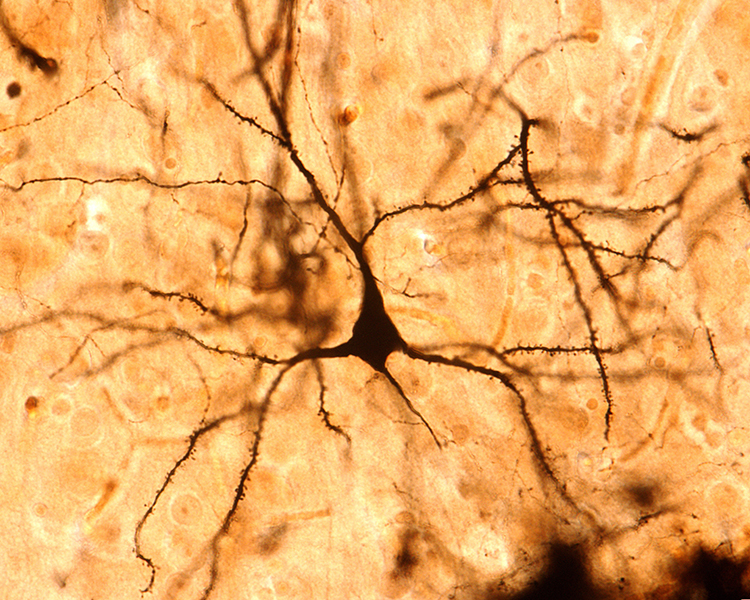

Astrocytes (shown below) communicate with each other and with neurons using gap junctions. Neurons that secrete hormones use electrical synapses to release their chemical messengers simultaneously. Neonatal brains may use gap junctions to activate many neurons at once. Image of long, fibrous astrocyte processes using Golgi's silver chromate technique © Jose Luis Calvo/Shutterstock.com.

Gap junctions may be a preliminary step toward developing chemical synapses between these neurons, eventually replacing their electrical synapses. Prenatally and postnatally, gap junctions enable nearby neurons to coordinate their development by sharing electrical and chemical communications (Bear, Connors, & Paradiso, 2020; Breedlove & Watson, 2020).

Old school view: synapses are either electrical or chemical.

New school view: synapses can be both electrical and chemical

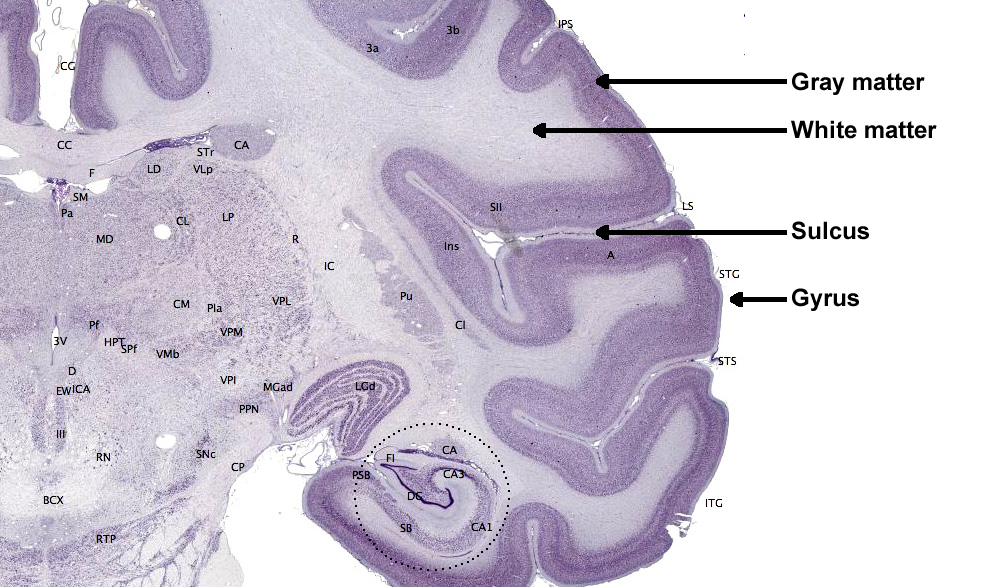

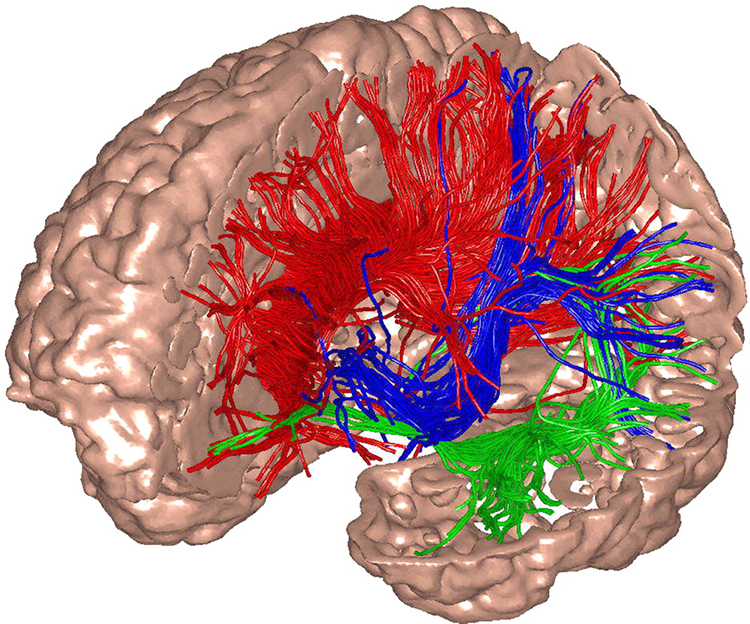

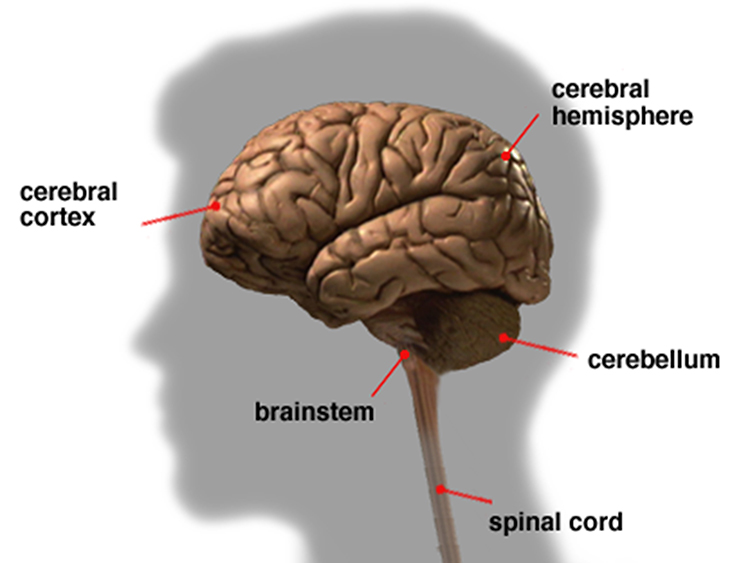

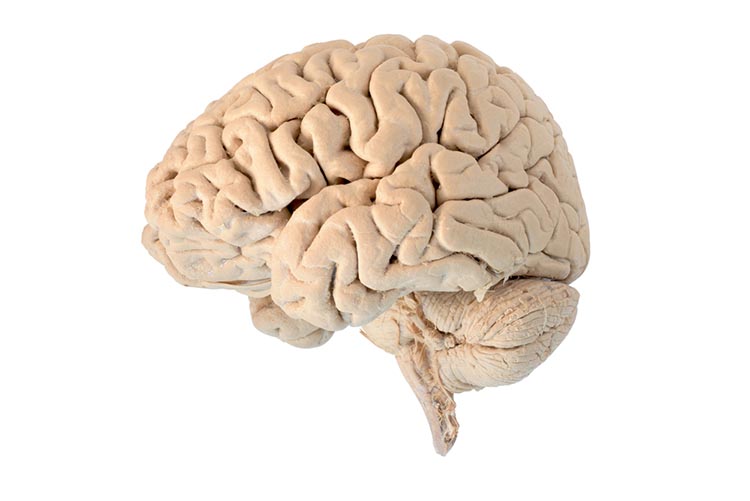

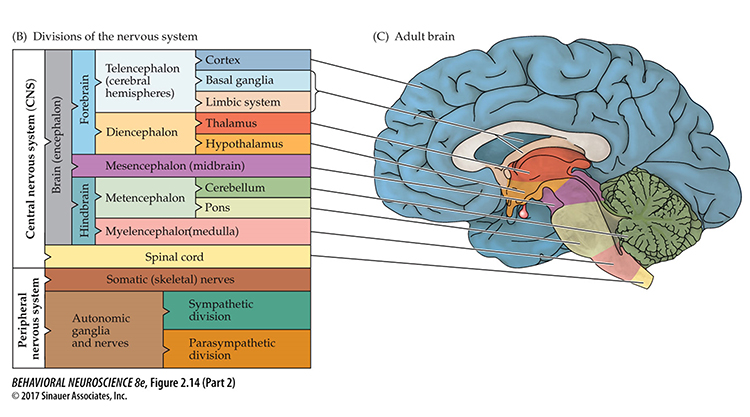

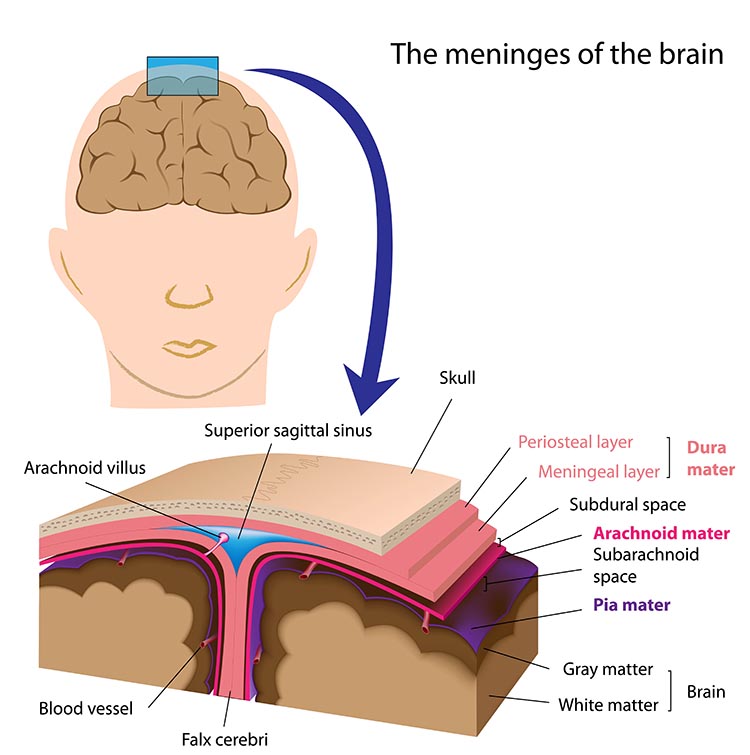

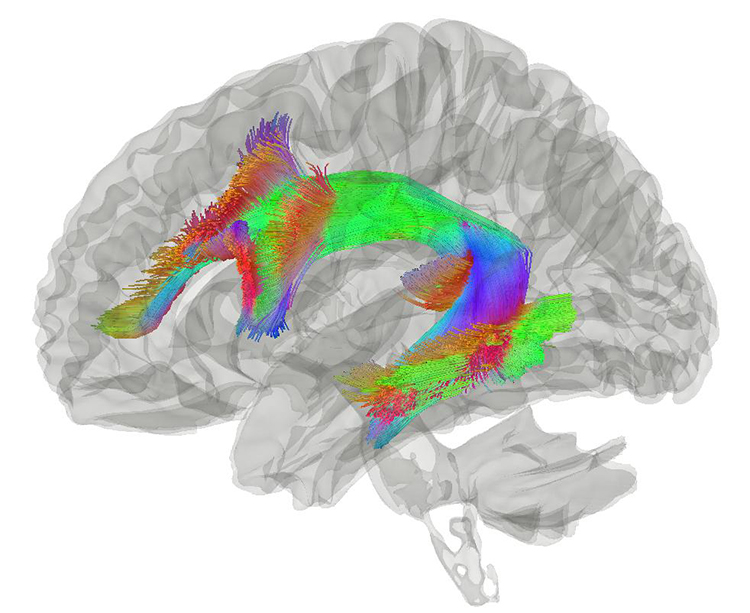

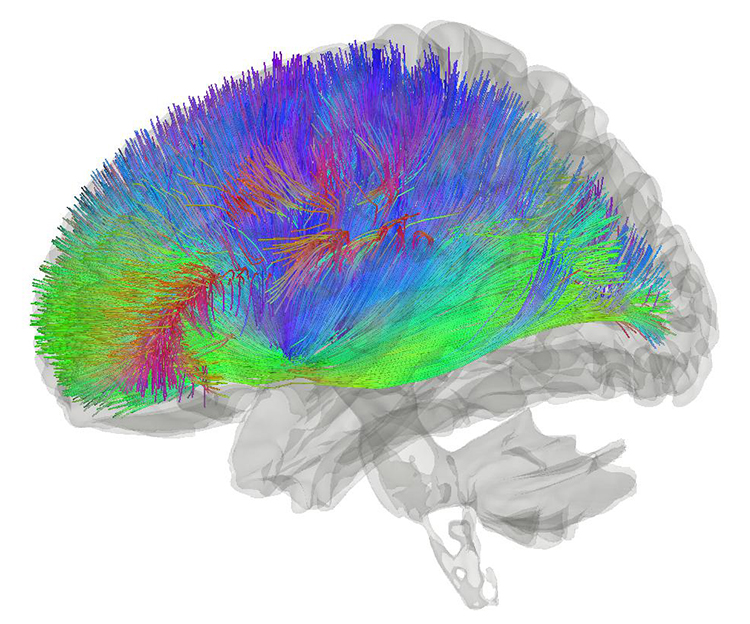

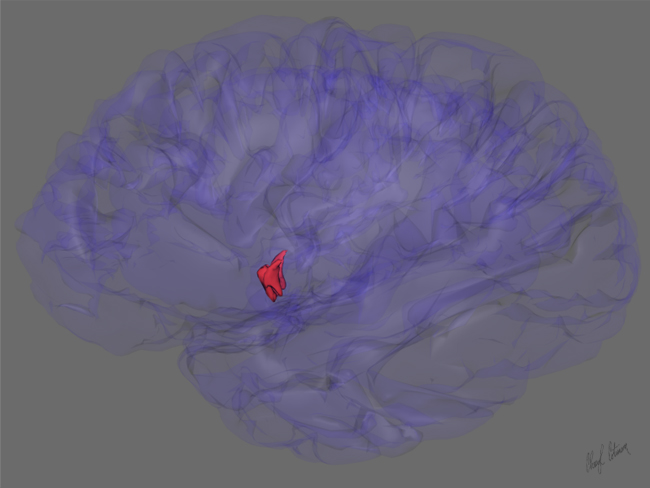

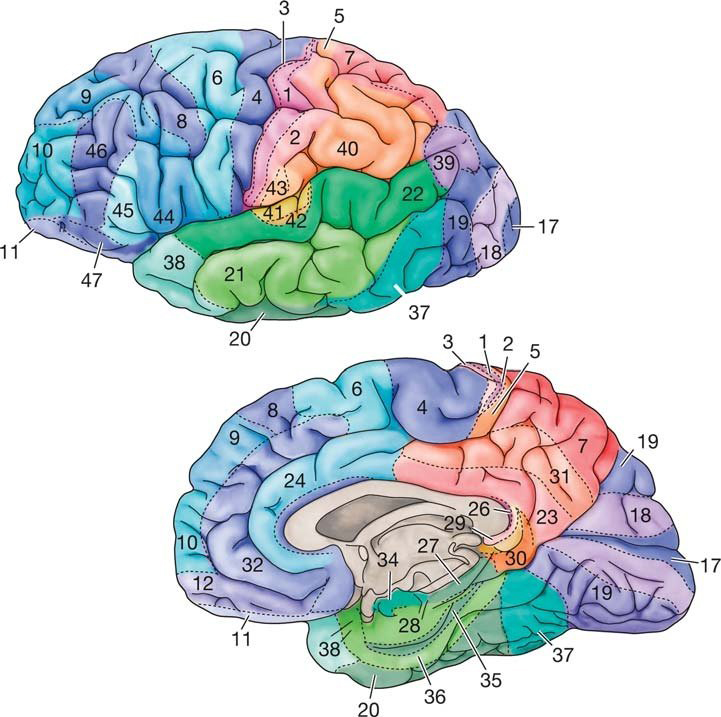

Cortical Architecture

While no one has counted the neurons in the human nervous system, a recent estimate is that an adult brain contains about 86 billion neurons (Voytek, 2013). Each neuron connects with an average of 40,000 synapses. There are 10 times more glial cells than neurons, and they comprise 50% of the brain’s volume (Breedlove & Watson, 2020). The 2 trillion glial cells are considerably smaller than neurons, with somas between 6 to 10 μm in diameter (Hammond, 1996). Animation © nmlfd/iStockphoto.com.The cerebral cortex comprises neuronal cell bodies, glial cells, and blood vessels. Beneath the neocortex lies myelinated nerves (white matter), unmyelinated fibers, and glial cells.

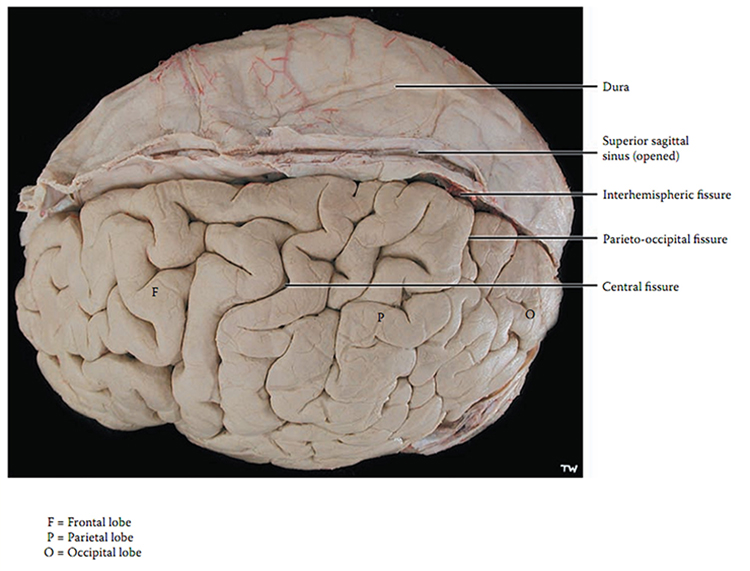

The cerebral cortex covers the cerebral hemispheres and consists of gray and white matter. Gray (or grey) matter, which looks grayish brown, comprises cell bodies. White matter gains its opaque white color from myelinated axons. The cerebral cortex of a macaque brain is shown below, courtesy of Wikipedia. Note that staining imparts a darker shade to gray matter.

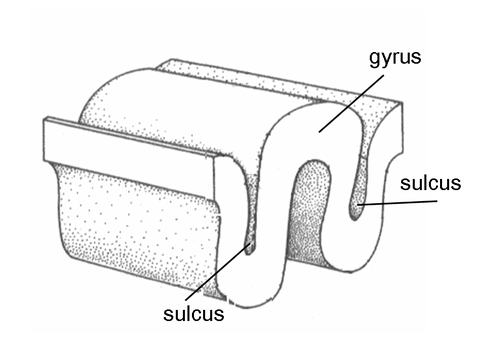

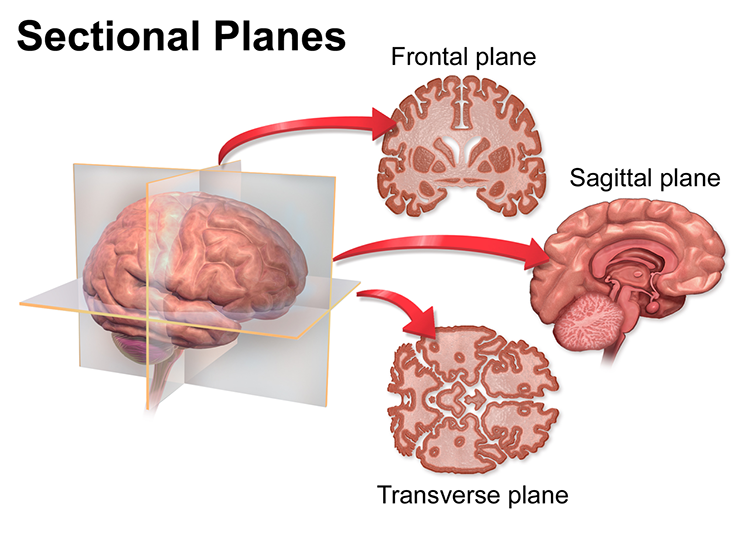

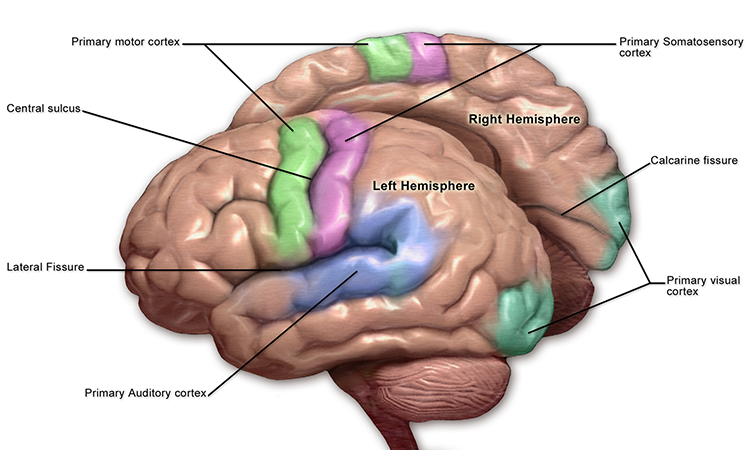

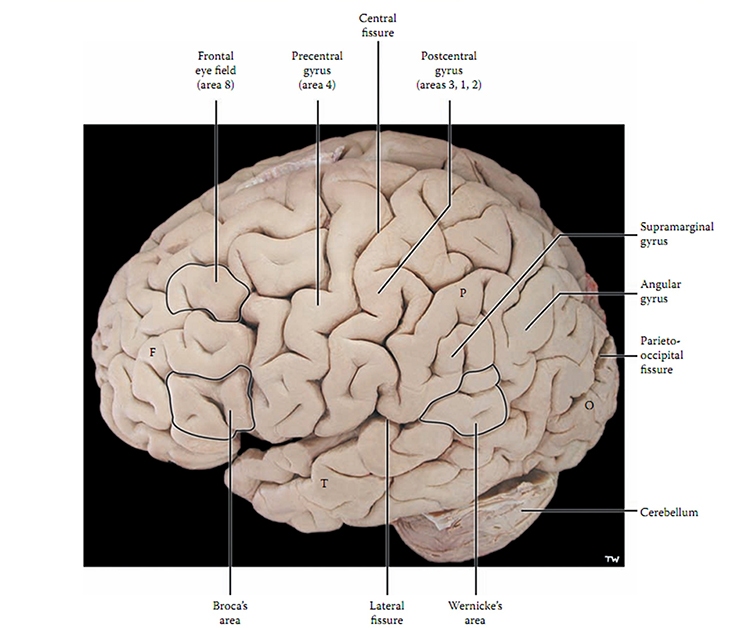

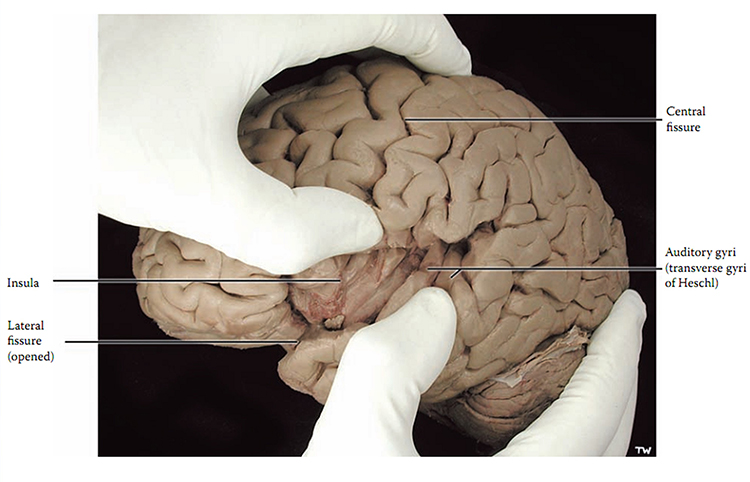

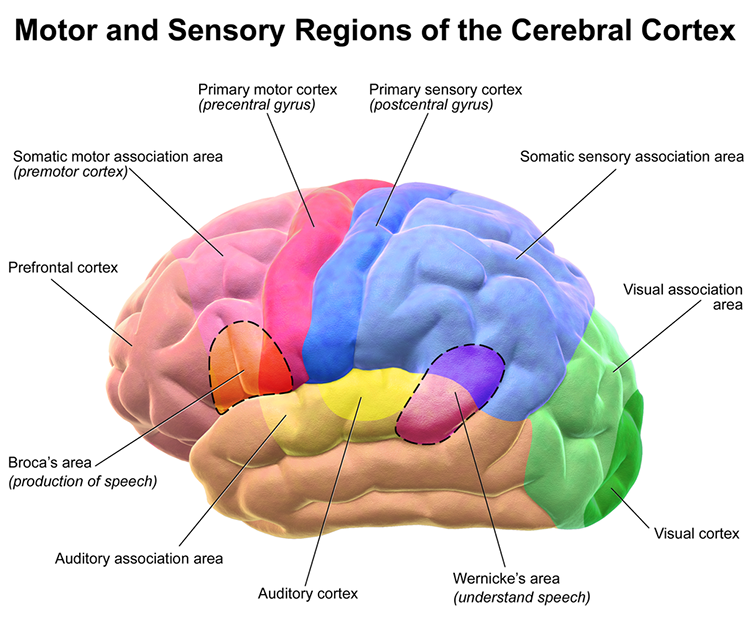

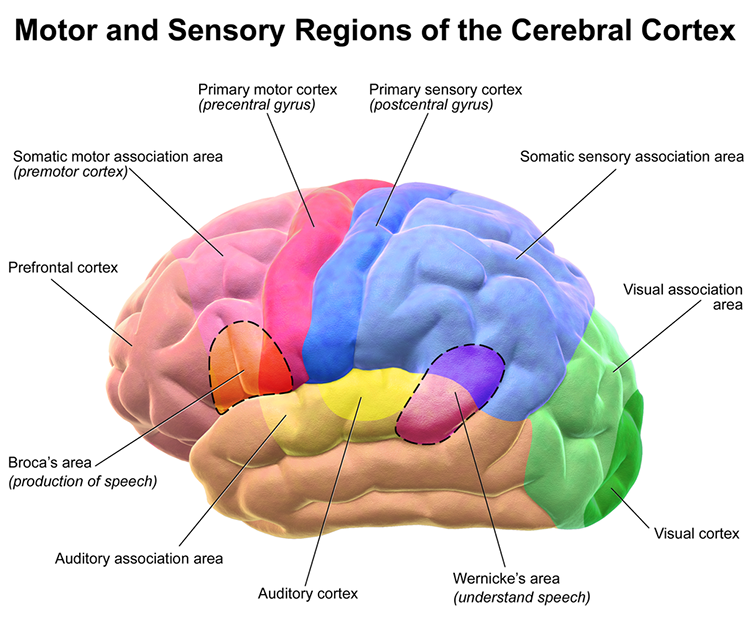

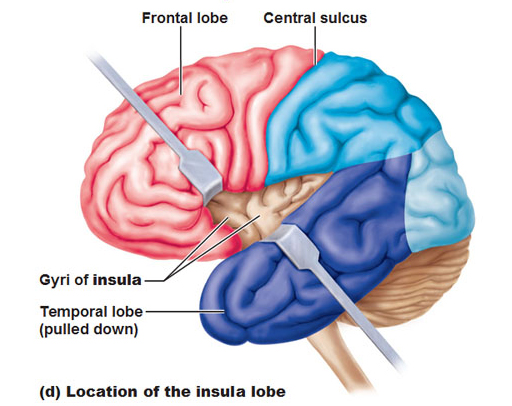

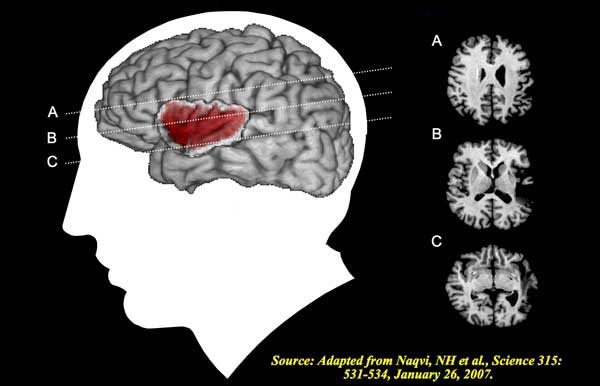

The convolutions of the cerebral cortex contain two-thirds of its surface area and maximize the volume of cortical tissue housed within the skull. Cerebral cortical convolutions include sulci, which are shallow grooves in the surface of the cerebral hemisphere (central sulcus), fissures, which are deep grooves (lateral fissure), and gyri, which are ridges of cortex demarcated by sulci or fissures (precentral gyrus) (Carlson & Birkett, 2021).

There are two main types of cortex: neocortex and allocortex.

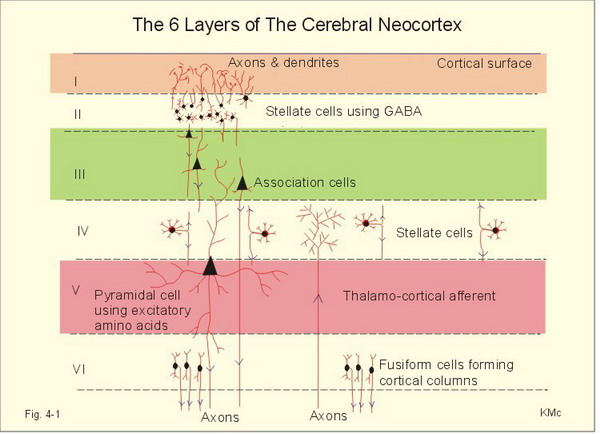

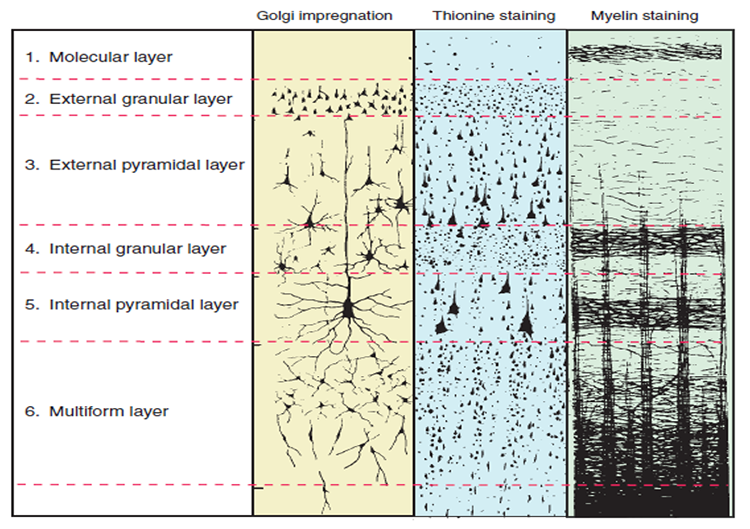

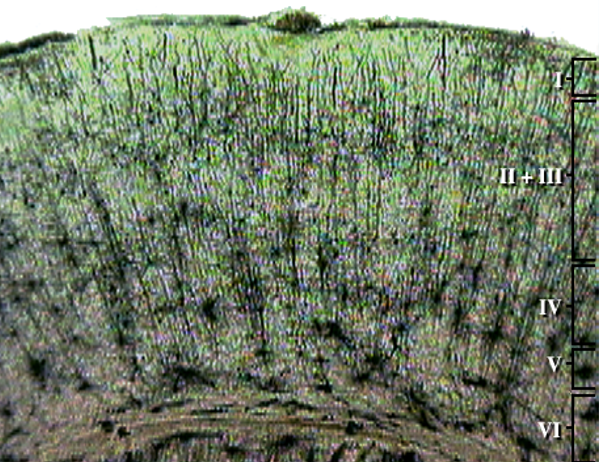

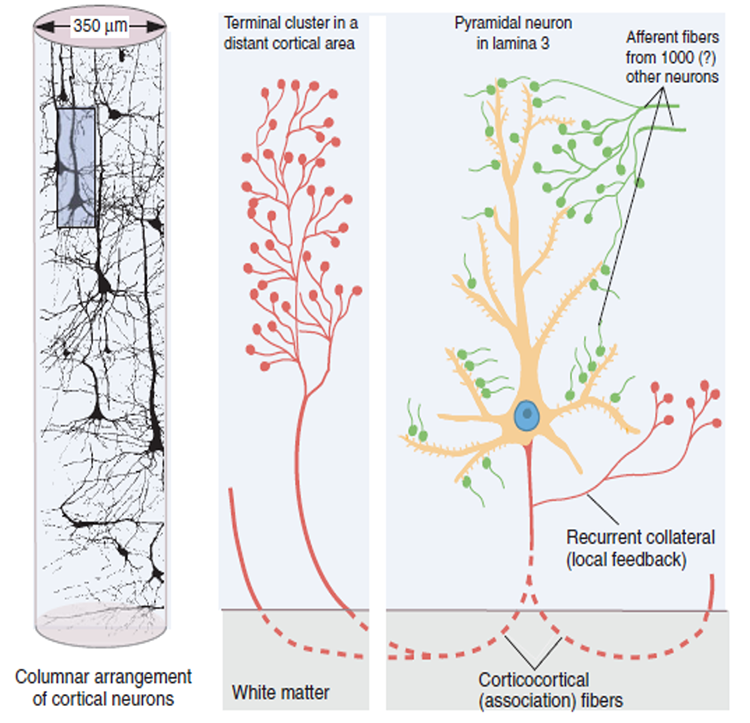

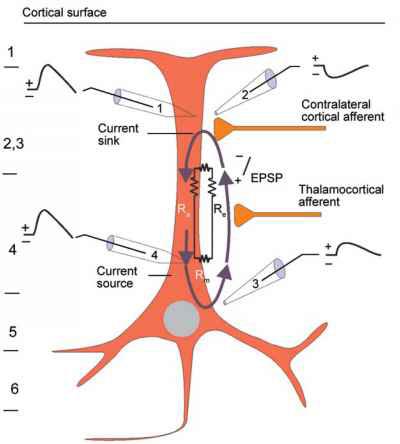

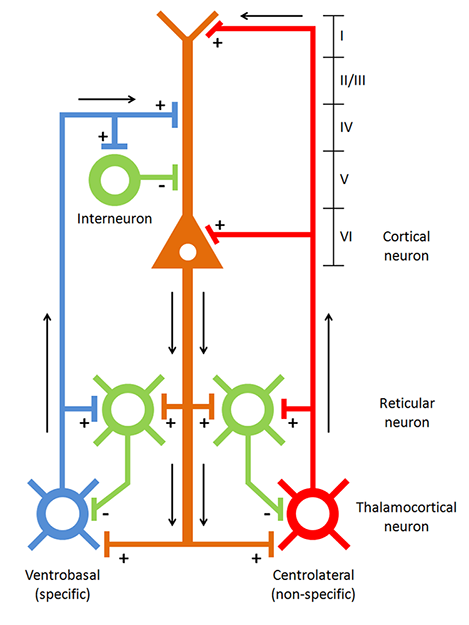

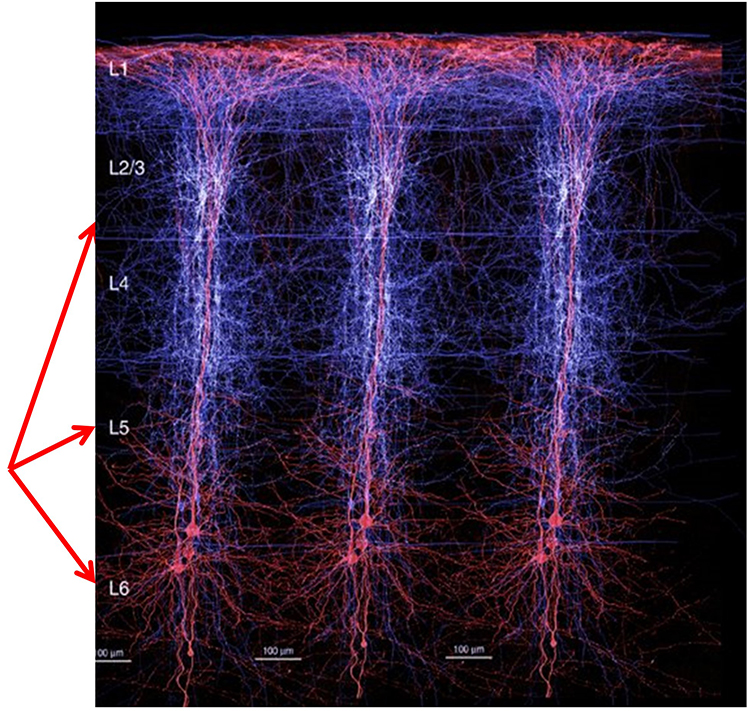

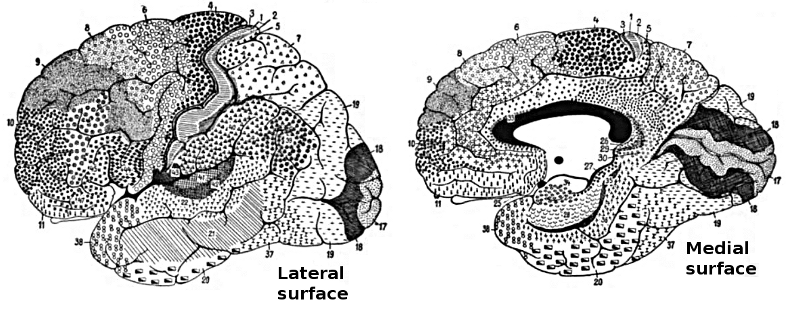

The neocortex or isocortex consists of six layers 3 mm thick with a surface area of about 2360 cm2 with white matter underneath. Layers I-III receive corticocortical afferent fibers that connect the left and right hemispheres. Layer III is the main source of corticocortical efferent fibers. Layer IV is the primary destination of thalamocortical afferents and intra-hemispheric corticocortical afferents. Layer V is the primary origin of efferent fibers that target subcortical structures that have motor functions. Layer VI projects corticothalamic efferent fibers to the thalamus, which together with the thalamocortical afferents, creates a dynamic and reciprocal relationship between these two structures (Creutzfeldt, 1995). Diagram courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Allocortex, which means other cortex, usually has between three or four layers, compared with the neocortex's six layers. The allocortex has less volume than the neocortex and comprises the olfactory system and hippocampus.

A transitional region between the neocortex and allocortex is called the paralimbic cortex.

For a basic overview of the cortex, watch the Khan Academy video Cerebral Cortex.

Neurons in the Cortex

We can classify cerebral cortical neurons as whether their dendrites display spines or not. Spiny neurons, which have either pyramidal or stellate (star-like)-shaped cell bodies, are usually excitatory. While all pyramidal cells are spiny neurons, stellate cells can be spiny or aspinous (Bear, Connors, & Paradiso, 2020).The graphic below depicts dendritic spines.

There are many types of aspinous (smooth) neurons, which are believed to be inhibitory.

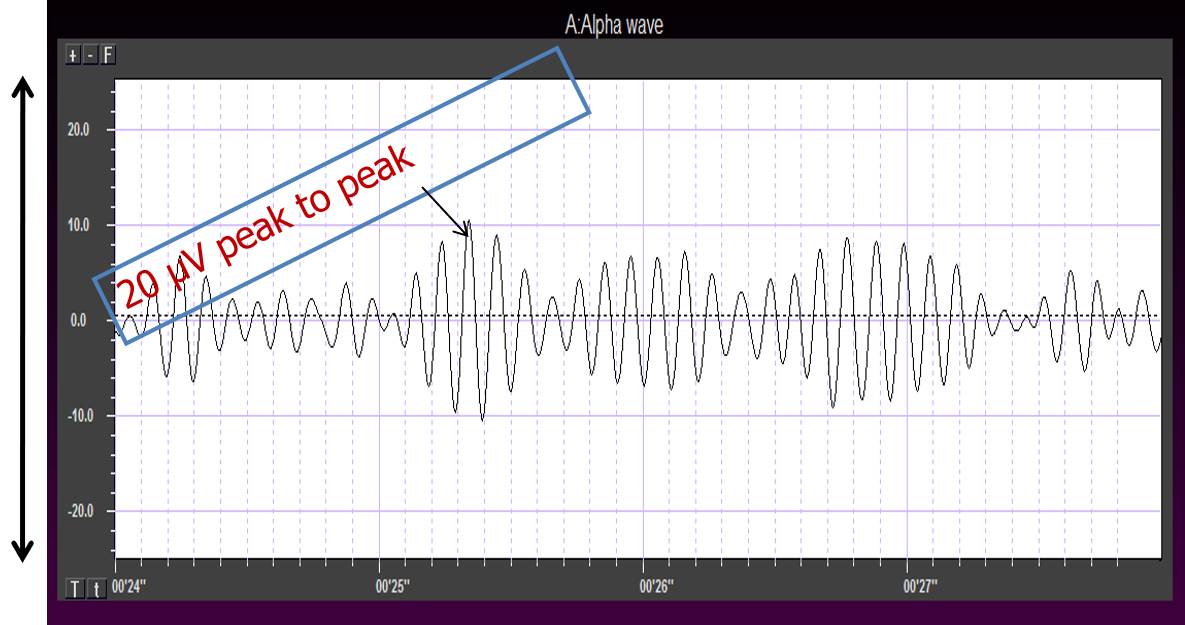

What is the EEG?

The scalp EEG is the voltage difference between two recording sites recorded over time. The EEG is primarily generated by large pyramidal neurons located in layers 3 and 5 of the 2-4.5-mm-thick cortical gray matter. Image of a pyramidal neuron revealed using Golgi silver chrome © Jose Luis Calvo/Shutterstock.com. Note that the apical dendrite arising from the cell body and basilar dendrites feature an extensive network of spines.

Local activity is a composite of local and network influences. Network communication systems and local cortical functions show different characteristics across the cortex and produce unique and specific EEG patterns in other regions.

The movie below is a display of the raw EEG with voltage shown as μV peak to peak © John S. Anderson.

What Can the EEG Tell Us?

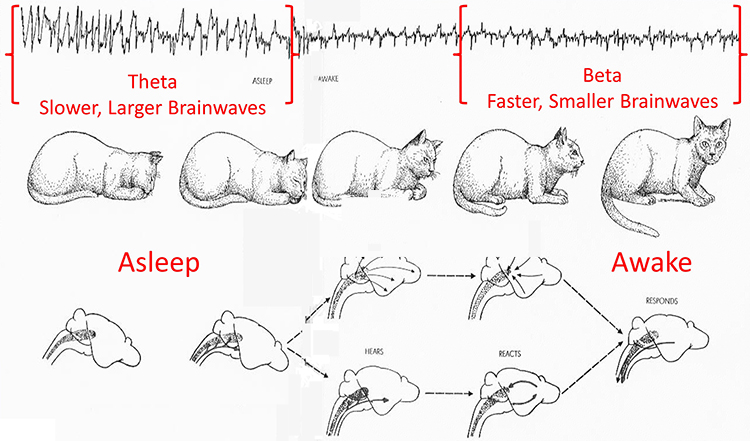

With the EEG, we can follow the progression from stimulus to behavior response. This allows us to determine the correct function at each step and identify causal factors in dysfunctional outcomes or responses.Source of the Scalp EEG

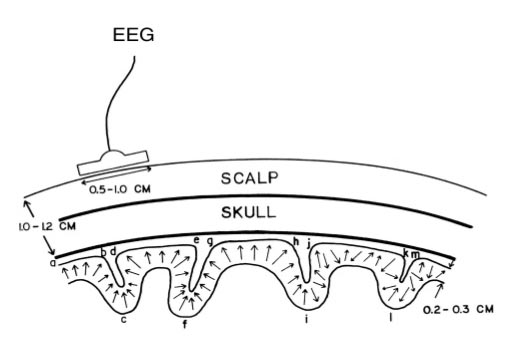

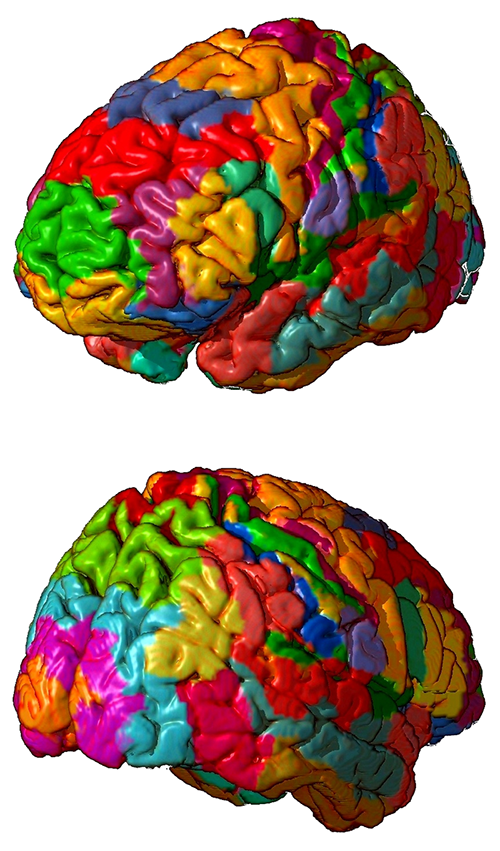

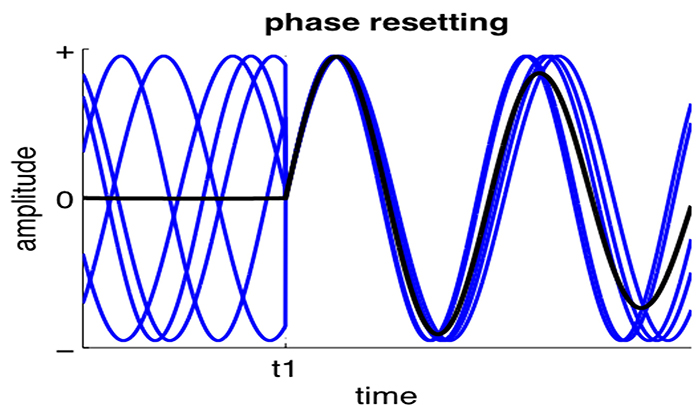

The scalp EEG results from the summation of large areas of gray matter activity. Areas are polarized synchronously due to the input of oscillatory or transient evoked activity. These areas comprise thousands of cortical columns containing large pyramidal cells aligned perpendicularly to the cortical surface.

Pyramidal neurons are found in all cortical layers, except layer 1, and represent the primary type of output neuron in the cerebral cortex.

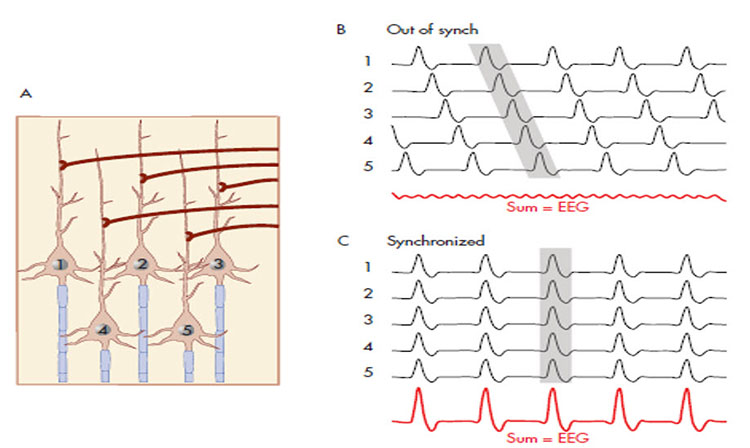

The scalp EEG results from the summation of EPSPs and IPSPs in thousands of cortical columns containing large pyramidal cells perpendicular to the cortical surface. The columns are synchronously polarized (made more negative) and depolarized (made less negative) due to the input of oscillatory or transient evoked activity.

Local Field Potentials

The local field potential (LFP) is the aggregate effect of the firing of the interconnected pyramidal neurons within the cortical columns, plus additional mechanisms like glial cell modulation of the cortical electrical gradient.

Caption from Wikipedia's article on Neural Oscillation. Simulation of neural oscillations at 10 Hz. The upper panel shows spiking of individual neurons (with each dot representing an individual action potential within the population of neurons). On the lower panel, the local field potential reflects their summed activity. This figure illustrates how synchronized patterns of action potentials may result in macroscopic oscillations that can be measured outside the scalp.

Do not confuse the "spiking" of individual neurons with epileptogenic spikes in the scalp EEG.

Scalp Electrical Potentials

Scalp electrical potentials represent the sum of all available electrical fields. Fields of opposite polarity (+/-) cancel each other out so that scalp potentials are greater when large aggregates of neurons polarize and depolarize synchronously. The scalp EEG represents a weighted sum of all active currents with the brain that generate open fields, including non-cortical sources.Action potentials reflect neuronal output. They are seen in extracellular recordings as fast (~300 Hz) activity that exceeds 90 mV lasting less than 2 ms. Action potentials play a minor role in scalp surface EEG. They fall below 60 V outside of a 50-μm (0.050-mm) radius. Scalp electrodes are several centimeters from cortical neurons and are generally aligned away from the scalp. Therefore, action potentials are unlikely to contribute significant voltages to the scalp EEG.

Local Field Potentials Regulate Neuron Excitability and Firing

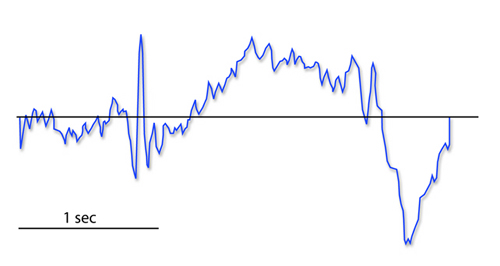

Neurons are most likely to fire during the depolarizing phase of the local field potential. Neurons are more excitable when they are "in phase" with respect to the local field potential (LFP) and are inhibited when they are out of phase with the LFP. Thus, at any instant of time, the amplitude and frequency of the EEG are regulated by the LFP, which in turn, is influenced by oscillatory mechanisms such as slow cortical potentials.The movie is a 19-channel display of SCPs © John S. Anderson. Negative SCPs drift down, and positive SCPs drift up. SCPs represent a global shift in DC voltage across the cortex and represent a generally higher (negative SCPs) or lower (positive SCPs) state of cortical excitability regulating neural networks.

The EEG is a moment-to-moment measure of the excitability of action potential firing, like gates opening and closing on the half cycle.

The synchronous activity of large pyramidal neurons networked in cortical columns creates the EEG.

The Composition of the EEG

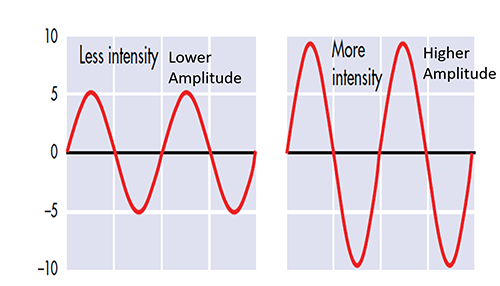

The EEG is composed of electrical potentials, varying in two dimensions, frequency and amplitude.

Sources of IPSP and EPSP Inputs

Many sources contribute input that results in IPSP and EPSP activity within cortical neurons. These sources primarily contribute influences such as oscillatory generator input or ascending event-related evoked input.EEG Sources

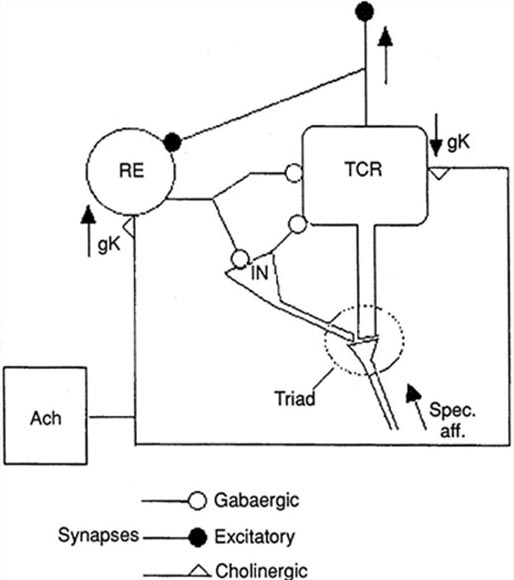

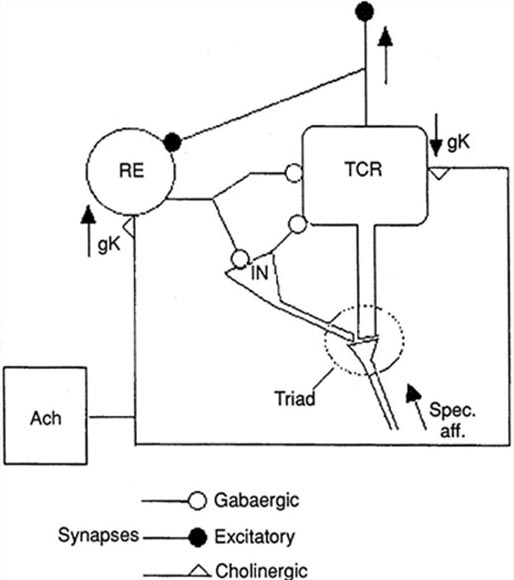

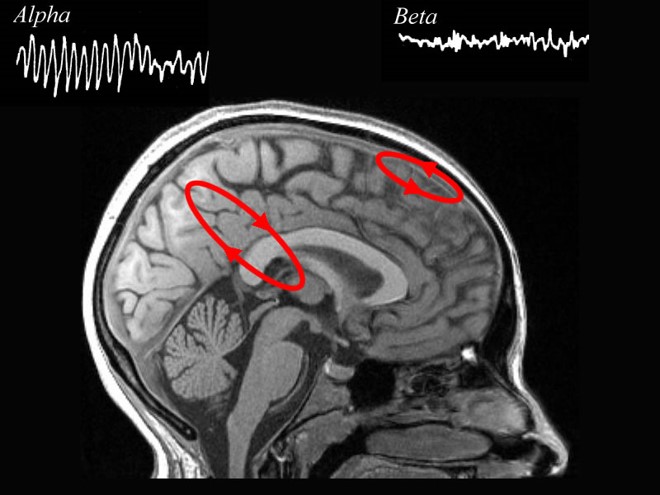

Generators like the thalamus produce oscillatory activity among many interconnected neurons, including EEG patterns like the alpha rhythm.

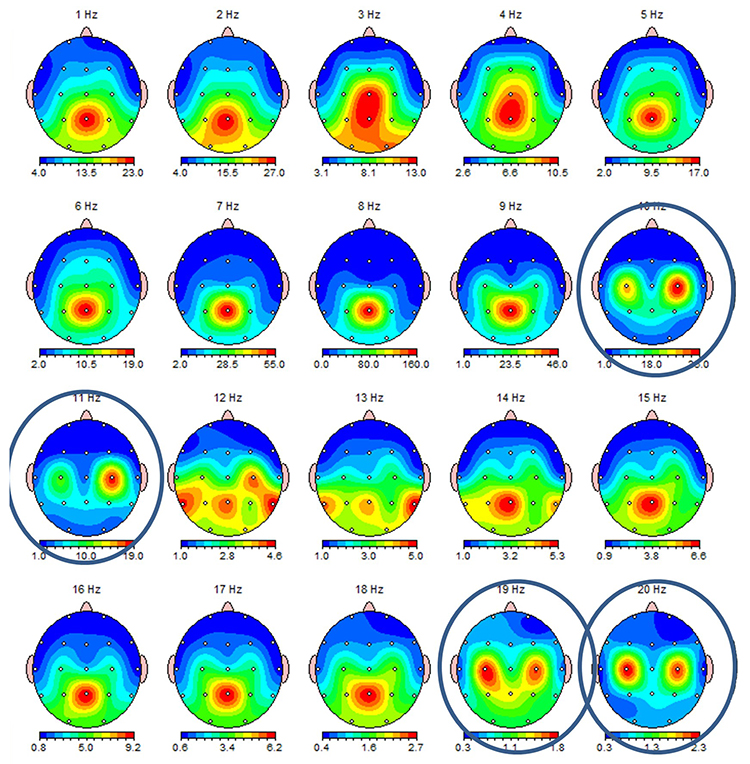

Movie © John S. Anderson. The recording begins with eyes open. The eyes-closed condition starts at 14’01” and clearly shows increased 8-12 Hz voltage (posterior dominant rhythm or PDR) in occipital and parietal locations in the line tracing and topographic maps to the right of the tracing.

The eyes open again at 14’31”, and alpha attenuates (alpha blocking). This shows the posterior dominant rhythm (generally known as "alpha") appearing in the eyes-closed condition when visual sensory input is stopped. The attenuation or blocking of this rhythm as sensory input returns in the eyes-open condition.

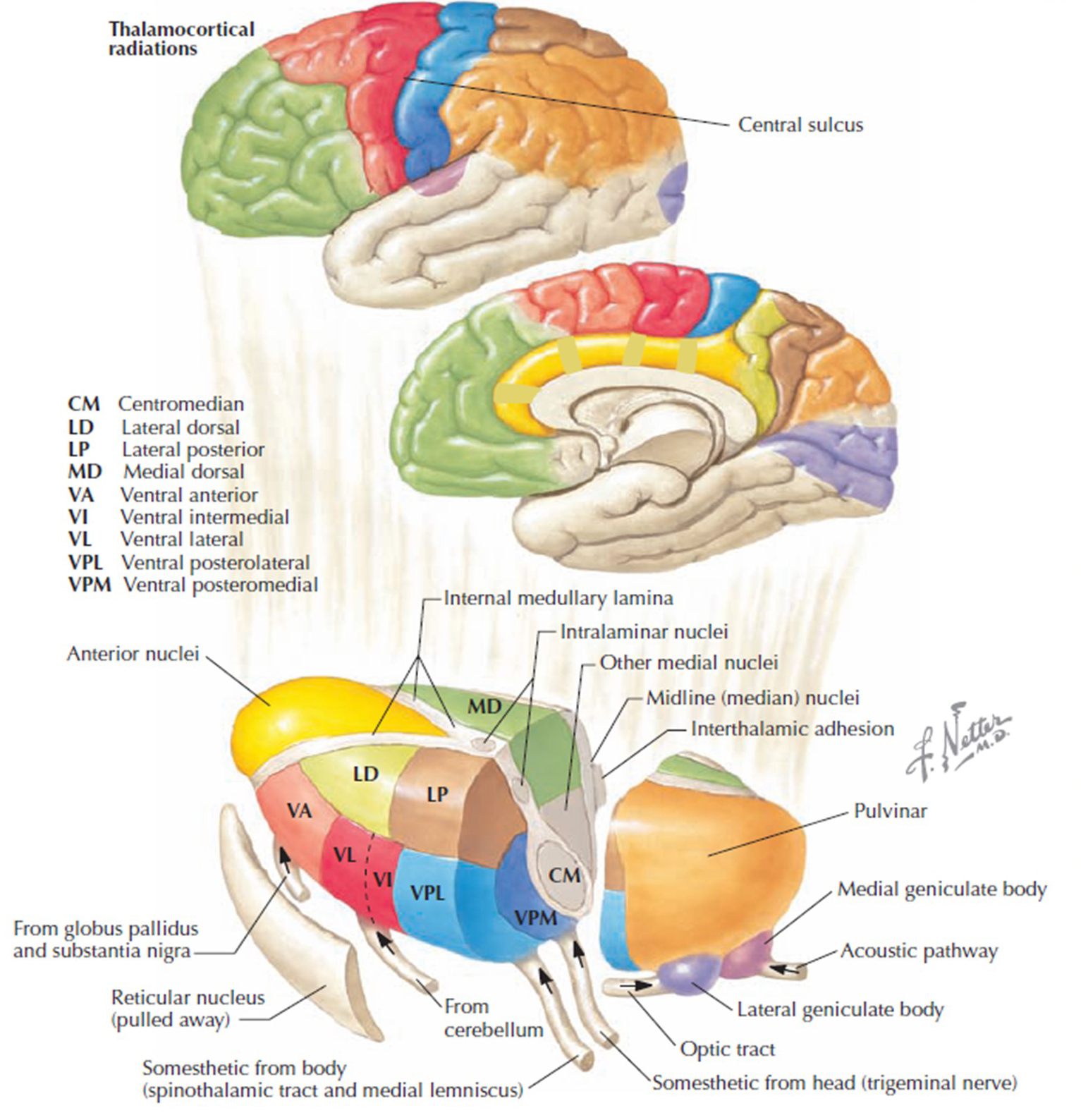

The thalamus contributes to slow cortical potentials, 1-4 Hz delta, 8-12 Hz alpha, and 20-38 Hz beta (including 40-Hz activity). The diagram shows the connections between the pulvinar (bottom right) and reticular nuclei (bottom left) of the thalamus and the cortex © Elsevier Inc. - Netterimages.com.

The diagram below, which shows bidirectional connections between the thalamus and cortex, was modified from the original on www.lib.mcg.edu.

Caption by W. D. Jackson, PhD, and S. D. Stoney, PhD (2006): Thalamocortical cells are subject to excitatory drive from their system afferents, from monosynaptic corticothalamic fibers, and from the brainstem reticular formation (ascending reticular activating system, ARAS). They receive inhibitory drive from local interneurons and neurons in the reticular nucleus of the thalamus (RNT). Note that the RNT neurons are excited by activity in thalamocortical cells and corticothalamic cells. The connections are precisely organized. For example, each column in a primary cortical area sends corticothalamic fibers back to the same part of its specific thalamic nucleus that sends its thalamocortical fibers to that cortical column. The corticothalamic fibers also synapse on the RNT cells receiving input from that part of the thalamic nucleus. Each cortical receiving area is said to be "reciprocally connected" with its specific thalamic nucleus. Like the thalamocortical cells, RNT cells and cortical neurons also receive excitatory drive from the ARAS.

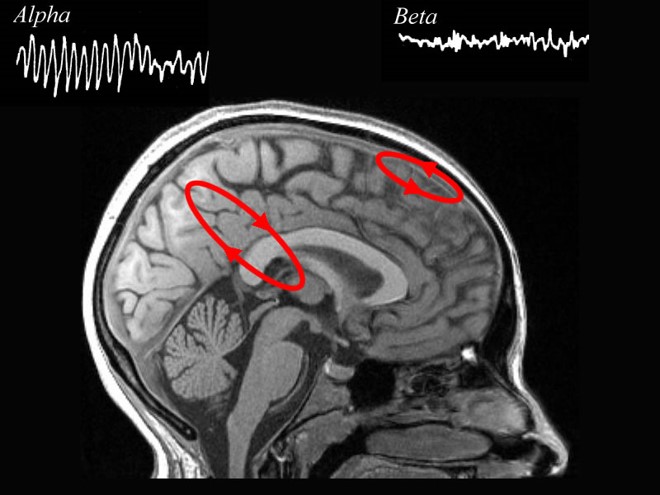

The EEG is generated by thalamocortical (alpha) and cortical-cortical (beta) sources.

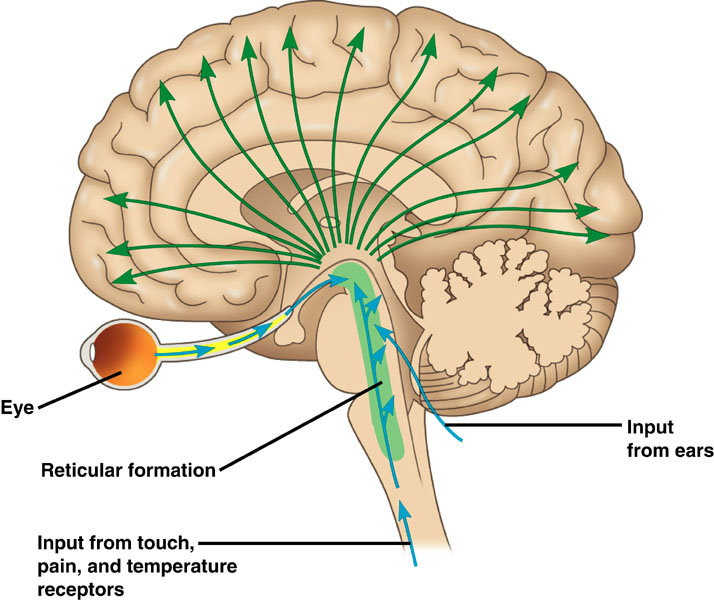

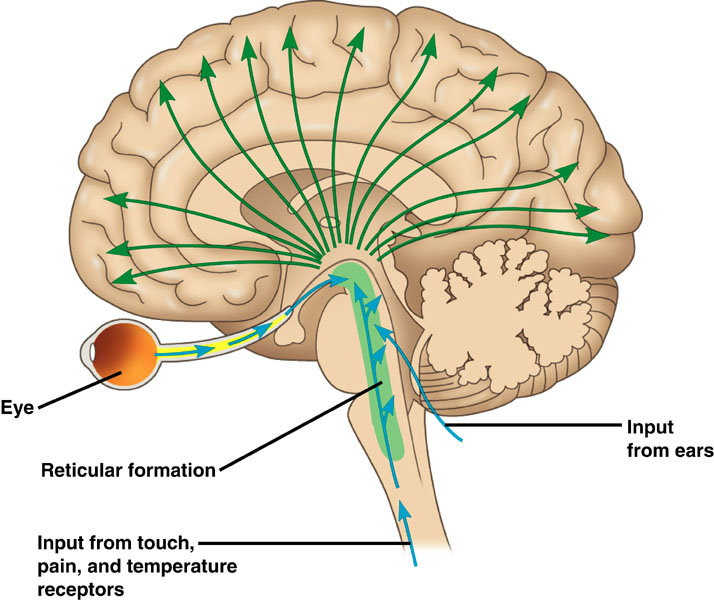

Neurons in the ascending reticular activating system produce event-related potentials in response to diverse stimuli like a flashing light or sound. Event-related potentials (ERPs) are the brain's response to externally applied stimuli, events, or cognitive/motor tasks. They are time-locked measures of brain electrical activity.

Dipole Generators

Large cortical pyramidal neurons organized in macrocolumns are oriented with an apical dendrite projecting toward the scalp and an axon descending in the opposite direction. An "Equivalent Dipole Generator" usually represents the sum of all multipolar current sources. Summed generators are modeled as dipoles to aid the conceptual understanding of the electrical fields involved.

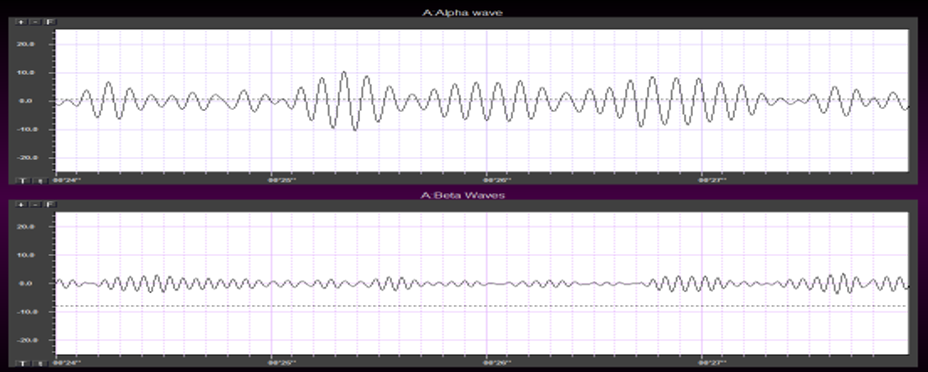

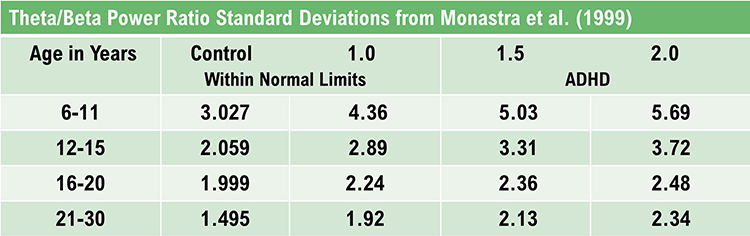

EEG Signals (Brainwaves)

The EEG represents changes in a brain area's electrical activity (potential) compared to a "neutral" site or another brain area. The EEG is displayed as oscillations or voltage fluctuations, which show a "wave" pattern when plotted on a graph.

"These oscillations are generated spontaneously in several areas of the cerebral cortex as neuronal networks transiently form assemblies of synchronously firing cells." Klaus Linkenkaer-Hansen.

Sink, Source, and Dipole

We can describe pyramidal cells in terms of their sink, source, and dipole. A sink (-ve), which may be located at the bottom, middle, or top of the apical dendrite, is where positive ions enter the dendrite. Cation (positive ion) entry gives the extracellular space a negative charge. The source (+ve) is where the current exits the cell. Finally, the dipole is the field created between the sink and source (Thompson & Thompson, 2016).The graphic below from Euroform Healthcare: Conduction Studies depicts current entering the apical dendrite (sink) of a pyramidal neuron where an afferent neuron has generated an EPSP. The current leaves the neuron (source) from the dendrite or cell body.

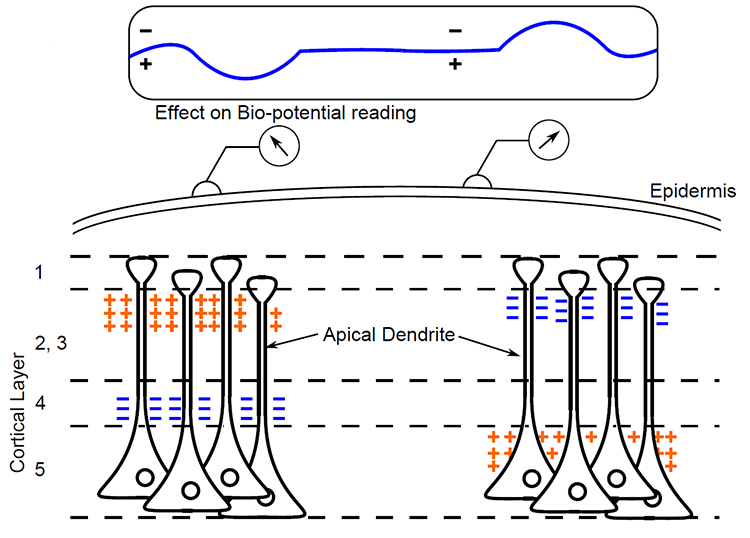

The postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs and IPSPs) propagated by the apical dendrites in layers 2 and 3 create an extracellular dipole layer parallel to the cortical surface. The dipole layer's electrical polarity is the opposite of the deeper cortical layers 4 and 5 (Fisch, 1999).

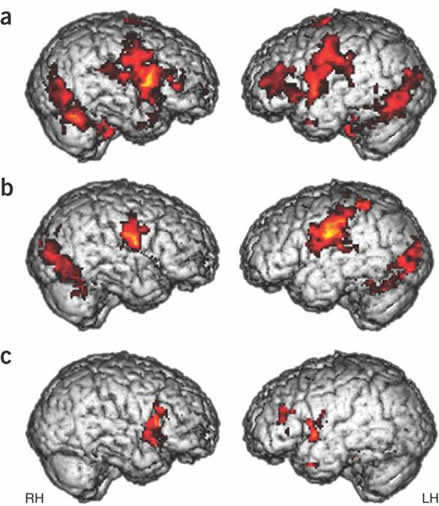

A cortical dipole is created when pyramidal neurons depolarize simultaneously. This phenomenon is called local synchrony. Fewer than 5% of pyramidal neurons can generate more than 90% of the power in the EEG signal because most pyramidal neurons usually fire asynchronously so that their potentials counteract each other. A small fraction of these neurons firing in step can produce visible changes in EEG feedback. This creates the potential for operant conditioning to help clients learn to modify EEG activity through neurofeedback.

Cortical dipoles have three properties: site (depends on source), size (oscillation frequency and voltage), and relative position with respect to sulci and gyri (Collura, 2014).

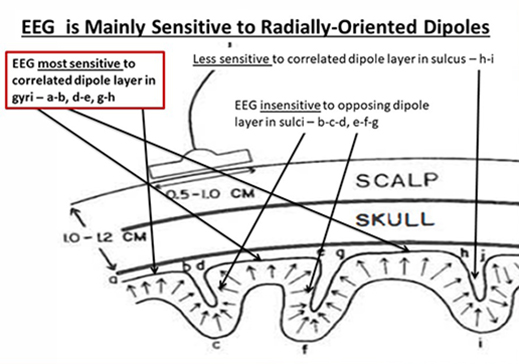

The EEG is Mainly Sensitive to Radially Oriented Dipoles

Evolution has convoluted the human brain to increase its computing power without enlarging the skull. This enfolding has created two easily visible anatomical features: gyri and sulci.

Recall that a gyrus is a ridge of the convoluted cerebral cortex, while a sulcus is a valley. The graphic below is courtesy of Wikipedia.com from the article Sulcus (neuroanatomy).

The EEG is most sensitive to a correlated dipole layer in gyri (a-b, d-e, and g-h). The EEG is less sensitive to a correlated dipole layer in sulci, valleys within the cortex (h-i). Finally, the EEG is insensitive to an opposing dipole layer in sulci (b-c-d, e-f-g). Graphic © Nunez (1995).

The EEG is composed of electrical potentials that vary along the dimensions of amplitude and frequency.

EEG Amplitude

The "amount" or amplitude and the "pattern" or morphology of any EEG frequency band reflect the number of neurons discharging simultaneously at that frequency. Lower neuron firing rates correspond to lower signal amplitude.

Amplitude measures the amount of energy in the signal and is usually expressed in microvolts.

Greater synchrony in firing among neurons results in higher amplitude, as shown with alpha in the graphic below.

Greater firing synchrony produces larger EEG potentials that can be measured from the scalp surface.

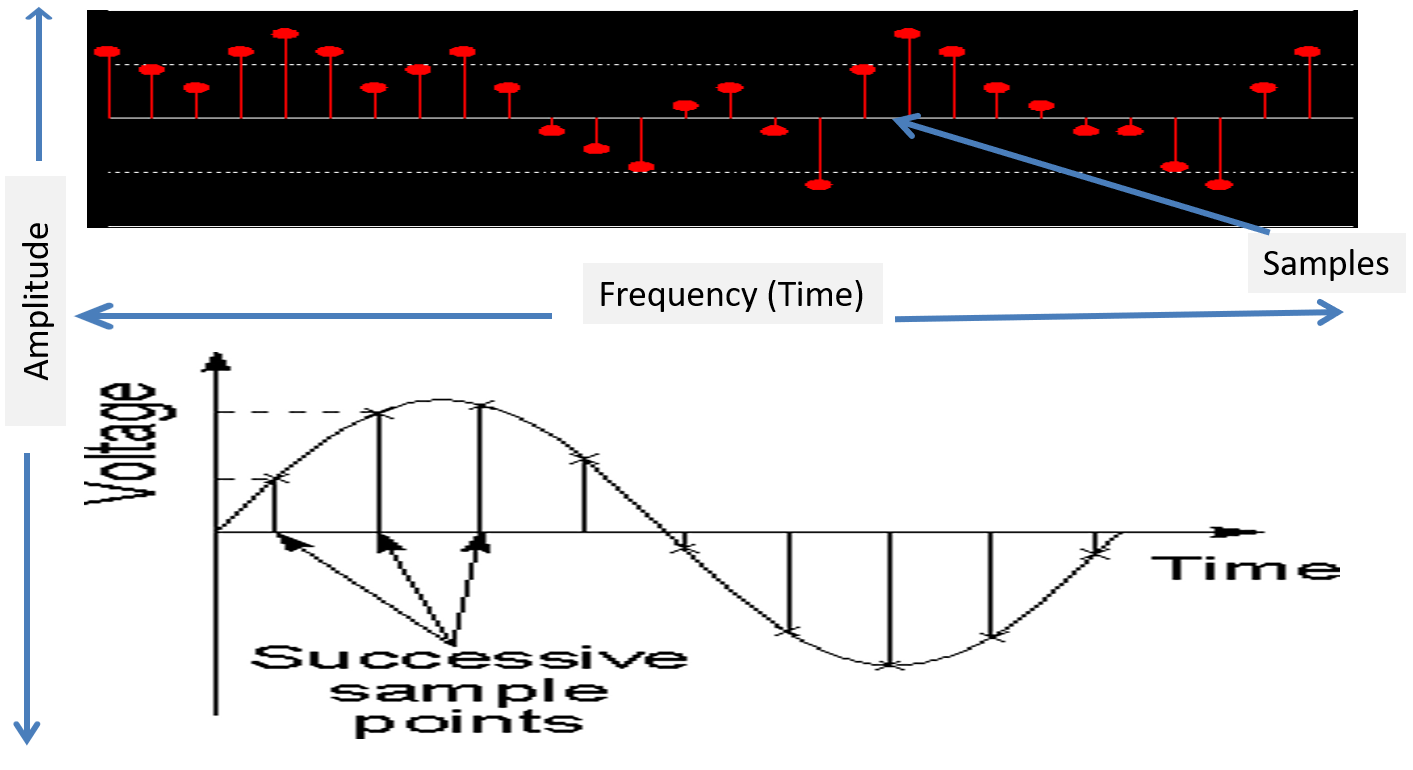

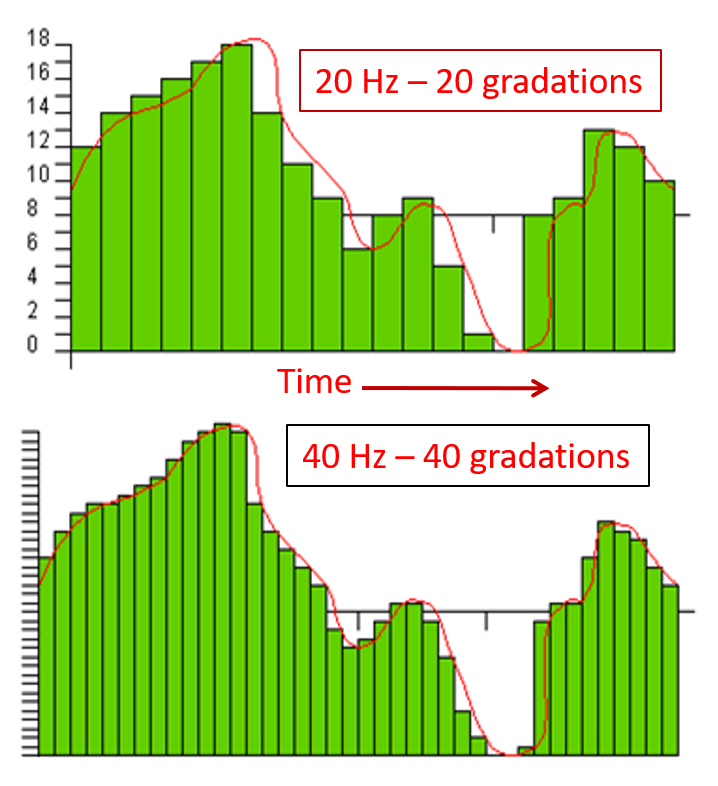

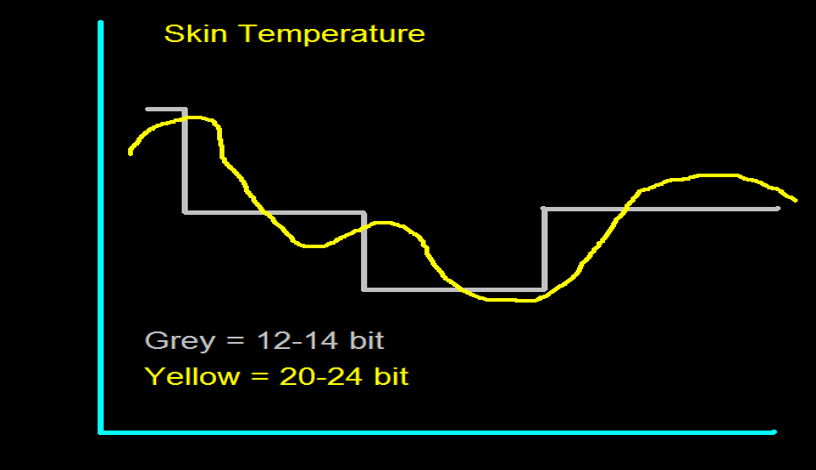

The EEG plots voltage changes over time, which can be displayed on a graph. The sampling rate is the number of measurements per second (Hz). Precision is the number of voltage gradations or steps.

The analog-to-digital (A/D) converters that transform voltages into numerical values vary in precision: more bits correspond to greater accuracy. The graphic below shows precision differences using 12-14-bit (grey) and 20-24-bit A/D converters.

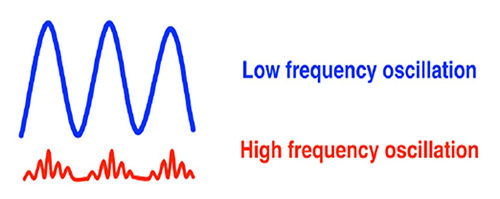

EEG Frequencies

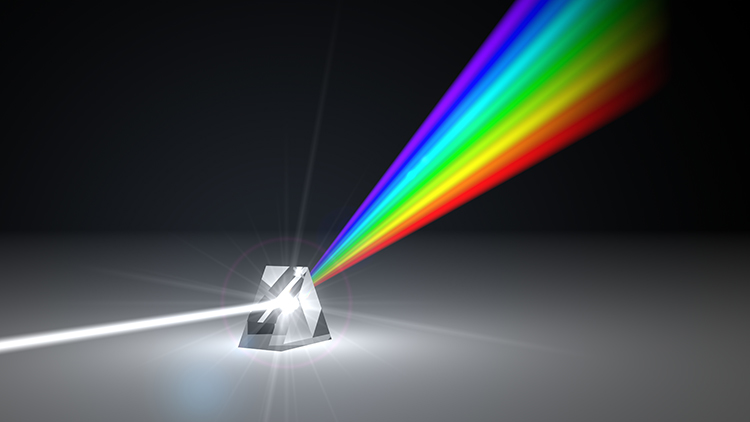

The raw EEG contains all EEG frequencies, just as white light contains all light frequencies. Digital filters separate the EEG frequencies just as a prism separates individual colors. Graphic © kmls/ Shutterstock.com.

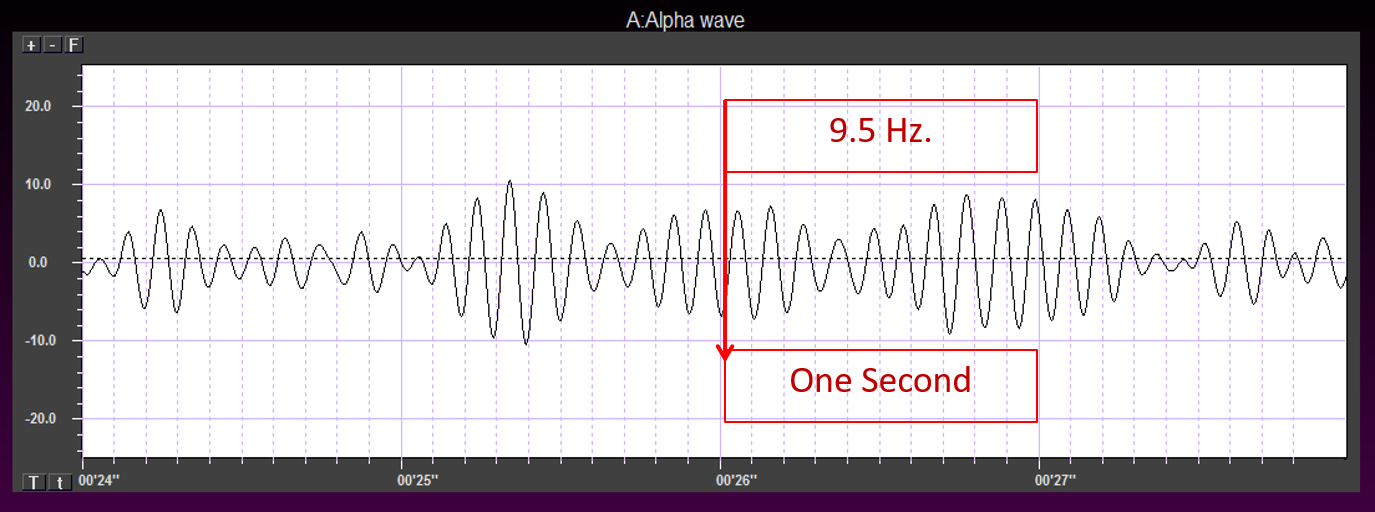

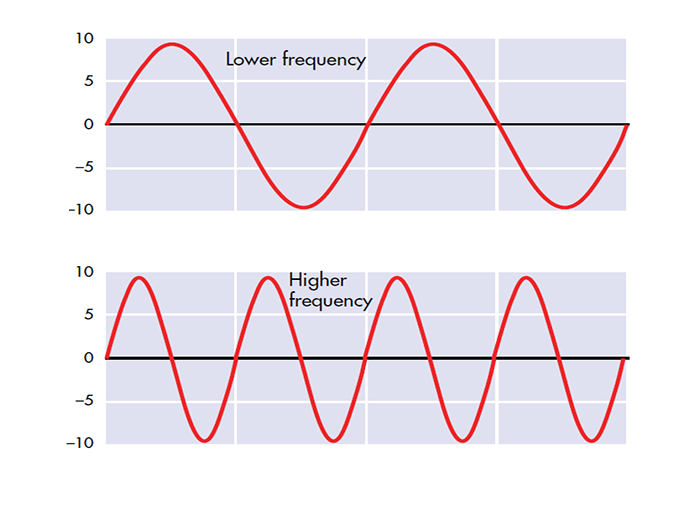

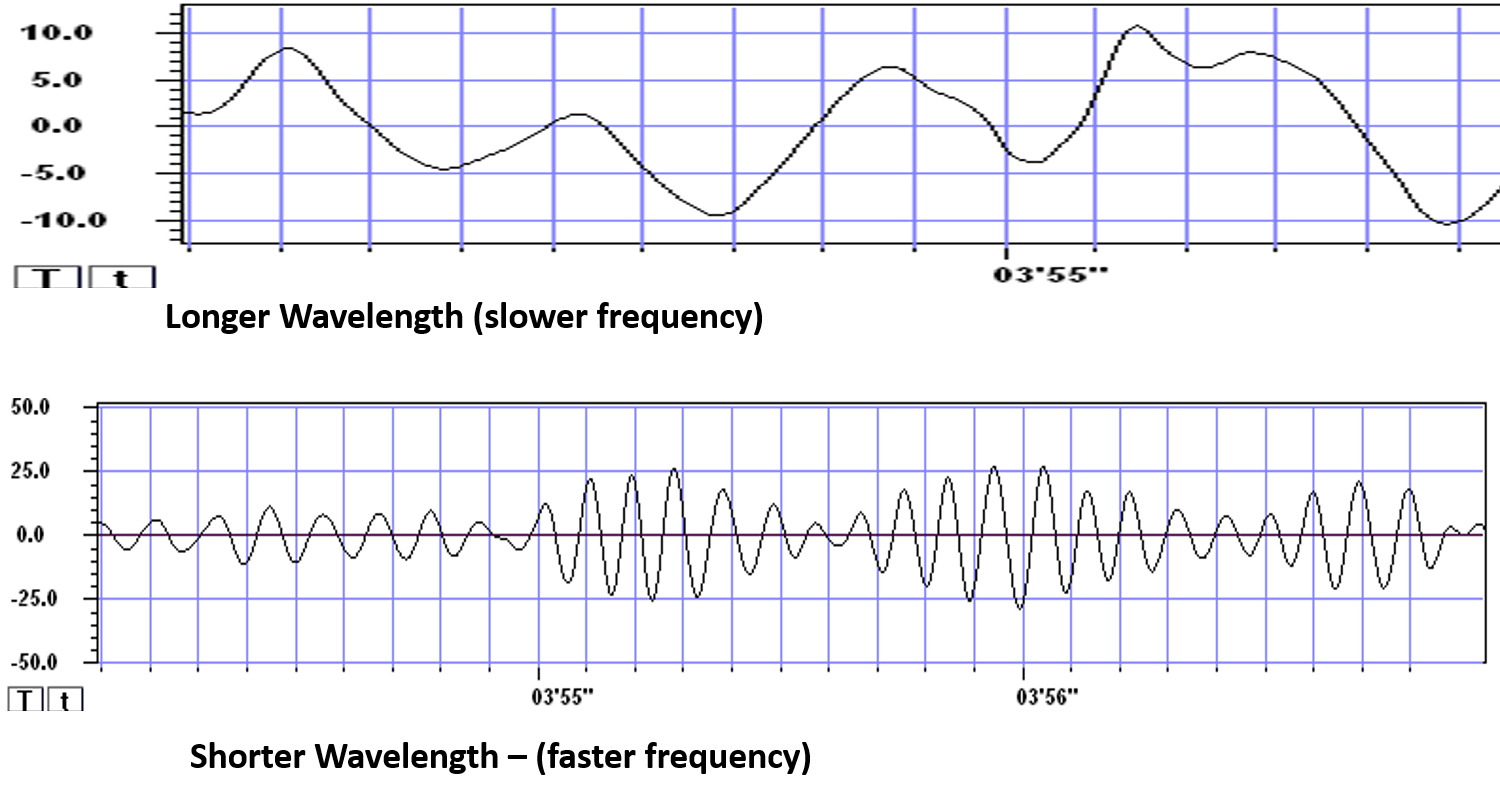

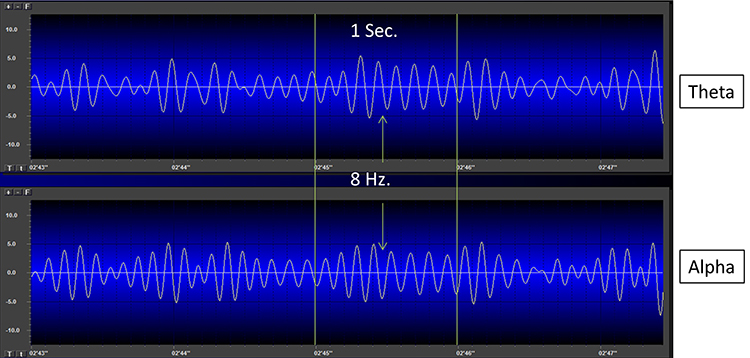

EEG frequency is measured in cycles per second or Hz. Count the number of peaks or count the number of zero (0.0) crossings divided by 2.

The slower the waves, the lower the EEG frequency.

The longer the wavelength, the slower the frequency.

The movie is a 19-channel display of EEG activity from 1-64 Hz activity broken into its component delta, theta, alpha, and beta frequency bands by digital filters © John S. Anderson.

The movie is a 19-channel display of alpha activity © John S. Anderson. Brighter colors represent higher alpha amplitudes. Frequency histograms are displayed for each channel. Notice the runs of high-amplitude alpha waves.

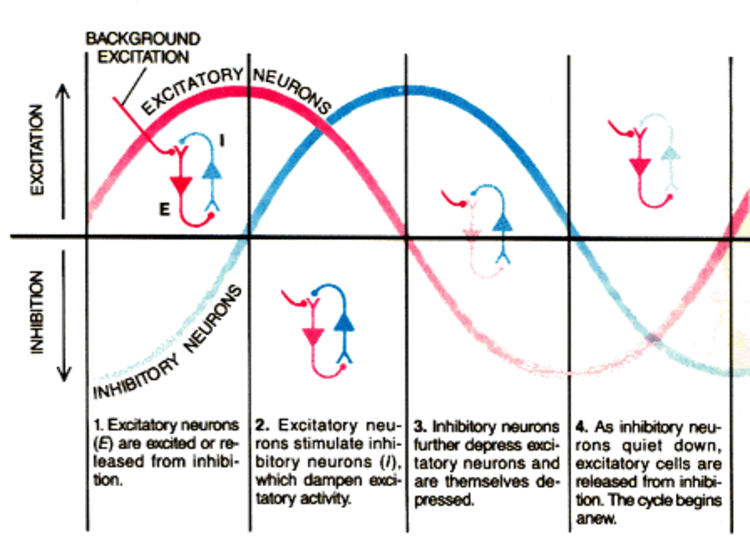

EEG Oscillations

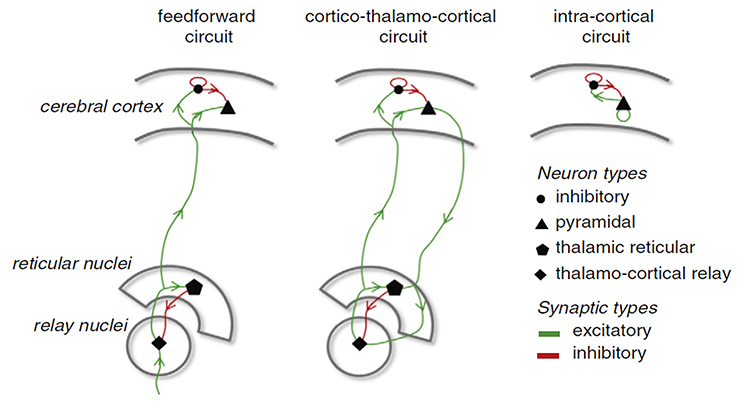

The generation of oscillatory activity, sometimes called spindle behavior, is likely due to the interaction between thalamocortical relay neurons (TCR), reticular nucleus neurons (RE), and interneurons. These interactions are mediated by diverse neurotransmitters, including acetylcholine and GABA.

Circuits Contributing to the EEG

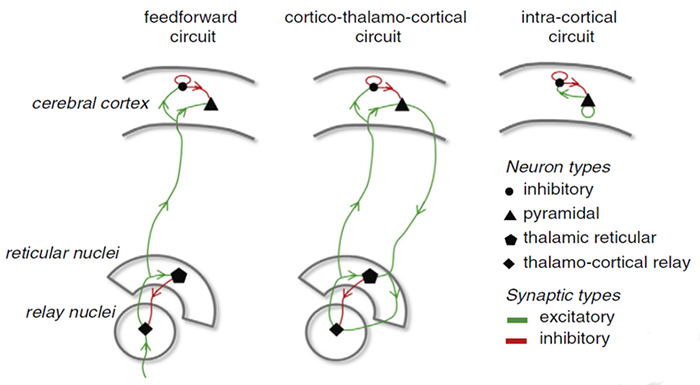

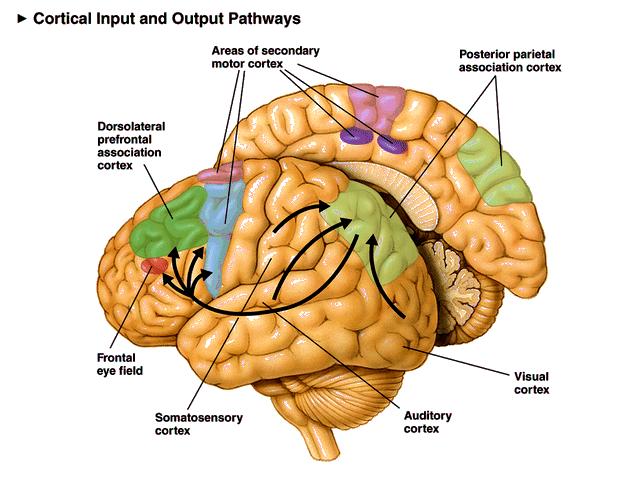

Feedforward, thalamocortical, and intra-cortical networks help generate the EEG. Graphic of circuits contributing to the EEG by Hindriks and van Putten © 2013 NeuroImage.

Spindling or Bursting Activity

Spindling is a synaptically-generated oscillation in a circuit that necessarily includes reticular nucleus neurons (RE).The movie below is a display of EEG spindling activity © John S. Anderson.

The various spindle frequencies, which have often been interpreted as reflecting different types of oscillations, merely depend on various durations of the hyperpolarizations (negative shifts) in thalamic-cortical relay neurons. Long duration hyperpolarizations, as during ... deeply EEG-synchronized states, are associated with 7 Hz or even lower-frequency spindles, while relatively short hyperpolarizations result in ... higher frequencies (14 Hz) (Steriade, 2005).

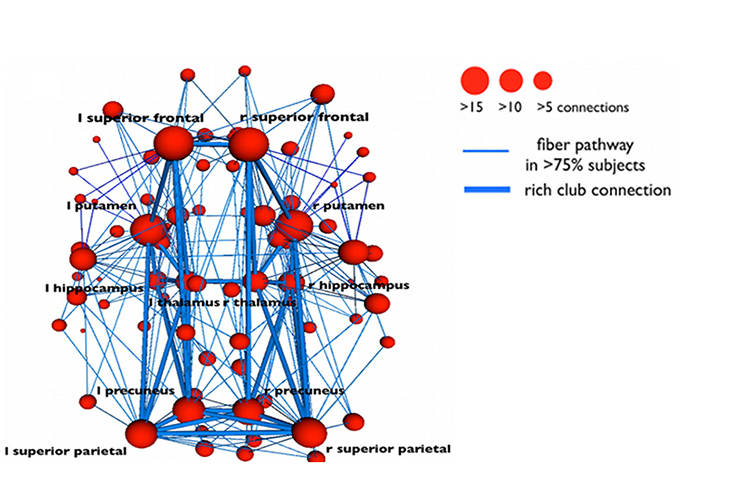

The Purpose of Oscillatory Activity

A single neuron can influence multiple postsynaptic targets located between 0.5 and 5 mm away with conduction periods of between 1 and 10 ms. This time difference becomes progressively more pronounced when more complex events involve progressively larger assemblies of neurons. It may take hundreds of thousands of neurons, stimulating multiple postsynaptic neurons, for the desired outcome to occur. When these many neurons are involved, it becomes increasingly clear that there is a need for organization and structure to manage this diverse activity.Timing is everything since action potentials arrive from a large number of sources. The nervous system must correctly register arrival times to recognize a face, recall a name, or remember personal history and context.

Hierarchical Processing

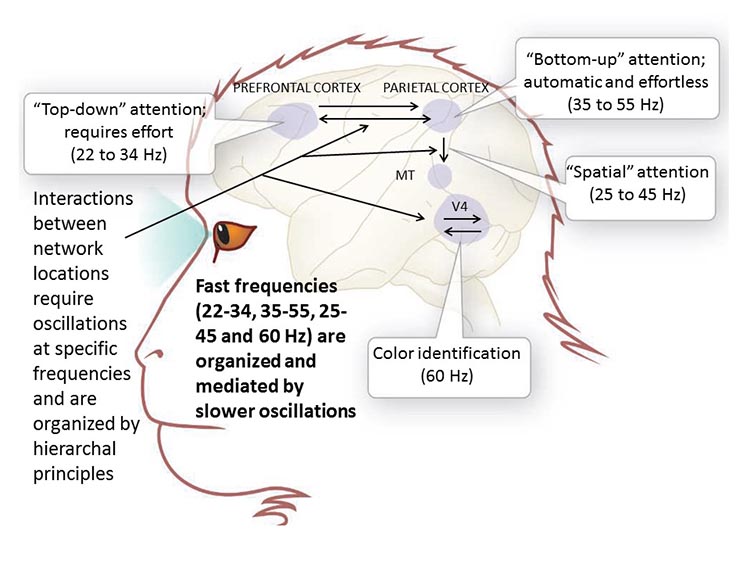

Complex events require that the systems involved operate within a spatial and temporal hierarchy. Each oscillatory cycle is a window of time within which processing can occur. Each cycle has a beginning, and an end within which encoded or transferred messages must complete their tasks. Groups of neurons, close or distant, interact most effectively when firing windows are synchronous. The brain does not operate continuously but in discontinuous packets. Graphic © Science by Knight (2007).

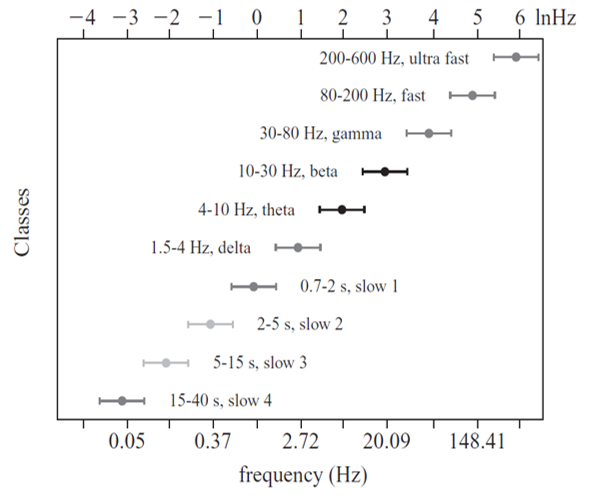

Multiple Oscillators

"Oscillatory classes in the cerebral cortex show a linear progression of the frequency classes on the log scale. In each class, the frequency ranges ('bandwidth') overlap with those of the neighboring classes, so that frequency coverage is more than four orders of magnitude" (Buzaki, 2006).

Frequency Determines Complexity

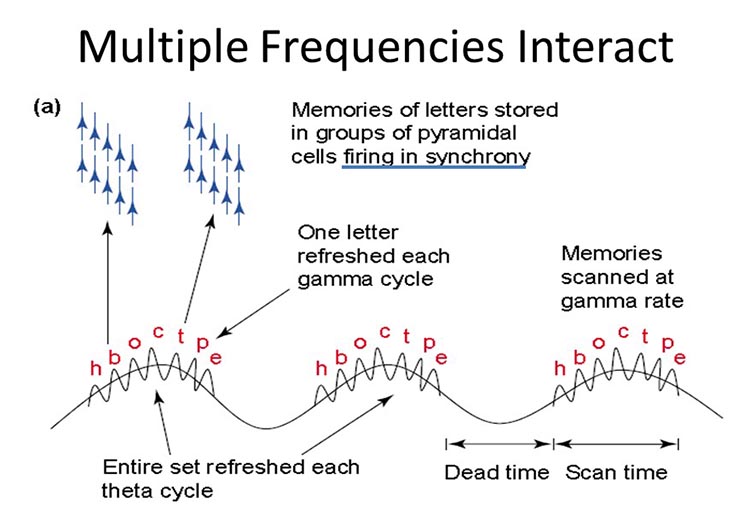

The wavelength or frequency of the EEG band determines how long the processing window will remain open and, therefore, the size of the neuronal pool involved. Because of the distances involved, longer wavelengths (slower frequencies) allow larger groups of more distant neurons to be assembled and coordinated. Different frequencies organize different types of connections and different levels of computational complexity.The graphic below © Trends in Cognitive Sciences by Ward (2003) illustrates the processing of memories of letters. One letter is refreshed during each gamma cycle, and memories are scanned at the gamma rate (frequencies above 30 or 35 Hz).

Local Versus Global Decision-Making

Short time windows of fast oscillators facilitate local integration, primarily because of the limitations of axon conduction delays. Fast oscillations favor local decisions. Slow oscillators can involve many neurons in large and/or distant brain areas. Slow oscillations favor complex, global decisions.Complexity Versus Frequency

Complex tasks involving sensory integration and decision-making were associated with 4-7 Hz synchronization. Intermediate tasks such as identifying spoken and written words and pictures increased 13-18 Hz beta activity. Simpler, more localized tasks, such as the visual processing of grid displays, were associated with faster-frequency activity (24-32 Hz) (Sarnthein et al., 1998; Von Stein et al., 1999).Traveling Waves Help Coordinate Widespread Brain Networks

Zhang et al. (2018) proposed that traveling waves between 2 to 15 Hz, moving at 0.25-0.75 meters per second across the cortex, mediate large-scale coordination of brain networks and support connectivity.Summary of EEG Oscillations

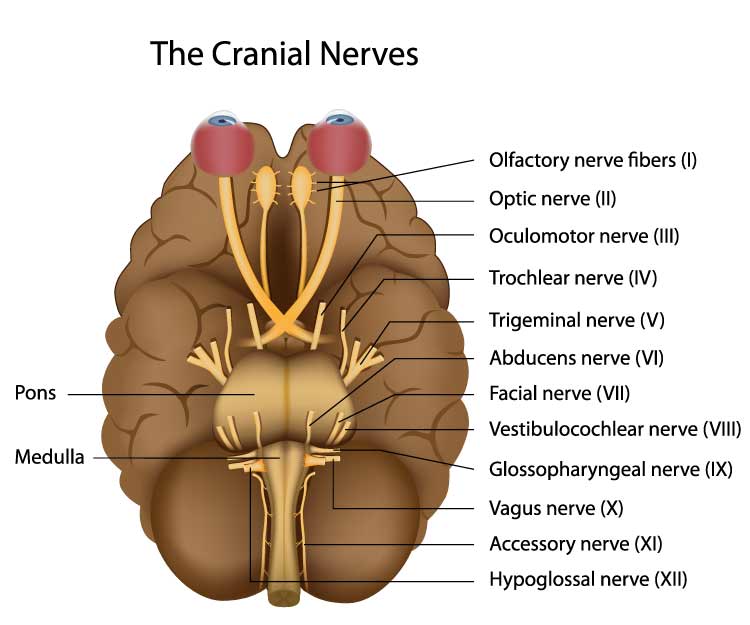

When the CNS processes incoming content, separate areas detect features of salient content, including visual, auditory, tactile, kinesthetic, and olfactory information. The CNS shares, integrates, compares current with previous content, analyzes, and makes decisions regarding memory and responses. Interacting networks linked by electrical and chemical signals perform this work. We record the electrical potentials generated by this complex and dynamic network activity as the EEG.The movie below of bursting alpha shows the sequential synchronization/desynchronization of groups of neurons. Higher voltage bursts are followed by voltage decreasing toward zero. These voltage fluctuations reflect rhythmic changes in the local field potential. This video © John S. Anderson.

DEFINITION OF ERPs AND SCPs

Sensory evoked potentials are a subset of event-related potentials (ERPs)

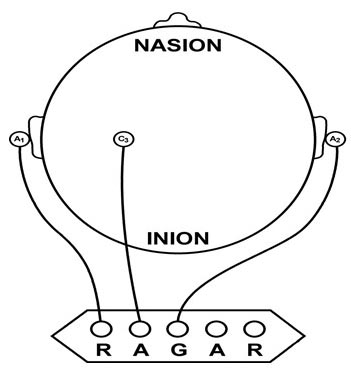

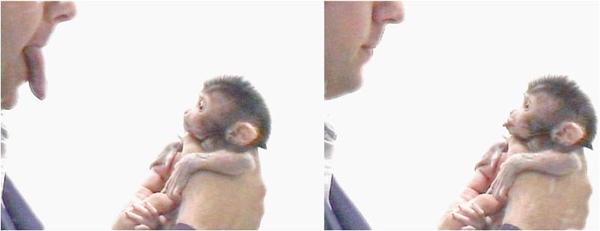

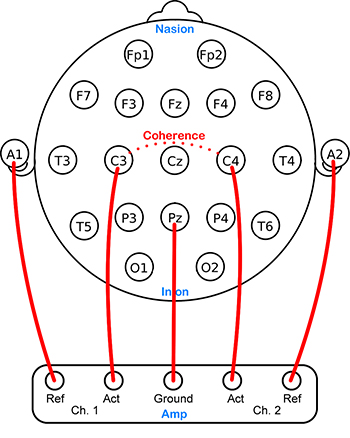

Event-related potentials (ERPs) represent the brain's responses to external stimuli, events, or cognitive/motor tasks. ERPs can be detected throughout the cortex. Investigators monitor ERPs by placing electrodes at areas like the midline (Fz, Cz, and Pz). A computer analyzes a subject's EEG responses to the same stimulus or task over many trials to subtract random EEG activity. ERPs always have the same waveform morphology. Their negative and positive peaks occur at regular intervals following the stimulus.Sensory evoked potentials are a subset of ERPs elicited by external sensory stimuli (auditory, olfactory, somatosensory, and visual). They have a negative peak at 80-90 ms and a positive peak at about 170 ms following stimulus onset. The orienting response ("What is it?") is a sensory ERP. The N1-P2 complex in the auditory cortex of the temporal cortex reveals whether an uncommunicative person can hear a stimulus.

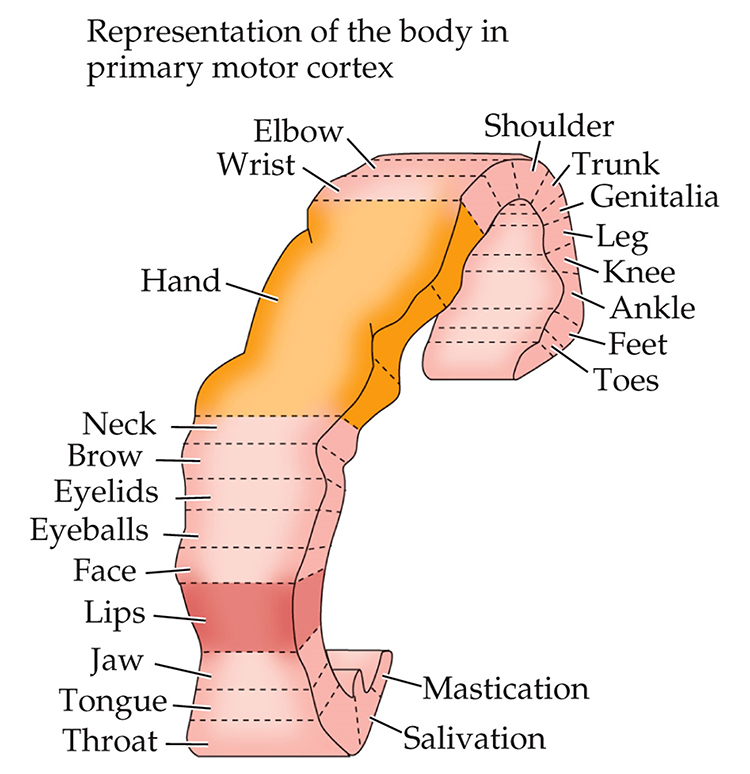

Motor ERPs are detected over the primary motor cortex (precentral gyrus) during movement, and their amplitude is proportional to the force and rate of skeletal muscle contraction (Thompson & Thompson, 2016).

Slow cortical potentials modulate the excitability of associated neurons

Slow cortical potentials (SCPs) are gradual changes in the membrane potentials of cortical dendrites that last from 300 ms to several seconds. These potentials include the contingent negative variation (CNV), readiness potential, movement-related potentials (MRPs), and P300 and N400 potentials, and exclude event-related potentials (ERPS) (Andreassi, 2007).SCPs modulate the firing rate of cortical pyramidal neurons by exciting or inhibiting their apical dendrites. They group the classical EEG rhythms using these synchronizing mechanisms (Steriade, 2005).

The movie is a 19-channel display of SCPs © John S. Anderson. Brighter colors represent higher SCP amplitudes. Negative SCPs drift down, and positive SCPs drift up. Negative SCPs are produced by the depolarization of apical dendrites and increase the probability of neuron firing. Positive SCPs are produced by the hyperpolarization of these dendrites and decrease the likelihood of neuron firing.

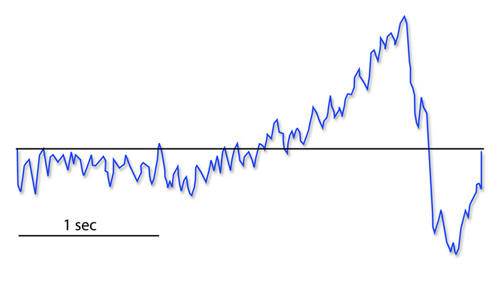

The contingent negative variation (CNV) is a steady, negative shift in potential (15 µV in young adults) detected at the vertex. This slow cortical potential may reflect expectancy, motivation, intention to act, or attention. The CNV appears 200-400 ms after a warning signal (S1), peaks within 400-900 ms, and sharply declines after a second stimulus that requires the performance of a response (S2). John Balven adapted the graphic below from Stern, Ray, and Quigley (2001).

The readiness potential is a slow-rising, negative potential (10-15 µV) detected at the vertex before voluntary and spontaneous movement. This slow cortical potential precedes voluntary movement by 0.5 to 1 second and peaks when the subject responds. This potential is separate from the CNV. John Balven adapted the graphic below from Stern, Ray, and Quigley (2001).

Movement-related potentials (MRPs) occur at 1 second as subjects prepare for unilateral voluntary movements. MRPs are distributed bilaterally with maximum amplitude at Cz. The supplementary motor area and primary motor and somatosensory cortices generate these potentials (Babiloni et al., 2002).

P300 and N400 ERPs are classified as long-latency potentials due to their extended latencies following stimulus onset.

The P300 potential is an event-related potential (ERP) with a 300-900-ms latency. The largest amplitude positive peaks are located over the parietal lobe. Researchers elicit the P300 potential by exposing subjects to an odd-ball stimulus, a meaningful stimulus that is different from others in a series (a colored playing card presented in a series of monochrome cards). The P300 potential may reflect an event’s subjective probability, meaning, and transmission of information. Research shows this is separate from the contingent negative variation (CNV) (Stern, Ray, & Quigley, 2001).

Shorter P300 latencies may reflect better allocation of attention, and researchers have measured longer P300 latencies in ADD than non-ADD samples. Experimental subjects show longer latencies when lying than when telling the truth (Farwell & Donchin, 1991; Thompson & Thompson, 2016).

The N400 potential is an event-related potential (ERP) elicited when we encounter semantic violations like ending a sentence with a semantically incongruent word ("The handsome prince married the beautiful fish"), or when the second word of a pair is unrelated to the first (BATTLE/GIRL). Warren and McIlvane (1998) speculate that the N400 potential is evoked whenever a general conceptual system that produces category judgments encounters a mismatch that violates equivalence relations. Halgren and colleagues (2002) consider it an index of the difficulty of semantic processing.

NEUROPLASTICITY (LTD AND LTP)

Neuroplasticity, the remodeling of neurons and neural networks with experience, is responsible for learning and memory. Memory storage involves the remodeling of neurons in terms of synaptic transmission, interneuron modulation, formation of new synapses, and rewiring of neural pathways (Bear, Connors, & Paradiso, 2020). Animal studies have shown that operant conditioning can induce astrogliogenesis (creation of new astrocytes) and neurogenesis (creation of new neurons) in structures like the medial prefrontal cortex and hippocampus (Rapanelli, Frick, & Zanutto, 2011).

The graphic is from synapse remodeling research by the Zuo Laboratory, MCD Biology, UCSC.

Neuroplasticity appears to involve a simple rule: when some synapses strengthen, adjacent synapses weaken to prevent overload due to increased input. A protein called Arc is crucial to this process (El-Boustani et al., 2018).

Neurofeedback, which involves the operant conditioning of CNS electrical activity, would be impossible without neuroplasticity. In neurofeedback, clients may learn to change the activity of local, regional, and global cortical resonant loops and the connectivity between brain regions (Collura, 2014; Thompson & Thompson, 2016).

To learn more about neuroplasticity, view the Khan Academy video Neuroplasticity.

Long-Term Depression and Long-term Potentiation

Two of the diverse processes involved in neuroplasticity are long-term depression and long-term potentiation.In long-term depression (LTD), synaptic transmission that coincides with slight depolarization of the postsynaptic neuron weakens a synapse due to pre- and postsynaptic changes. Relatively low-frequency stimulation of afferent neurons reduces the magnitude of their response to future stimulation

In long-term potentiation (LTP), synaptic transmission that coincides with strong depolarization of the postsynaptic neuron strengthens a synapse due to pre- and postsynaptic changes. Strong stimulation of afferent neurons results in a stable and persistent (weeks or more) increase in synaptic effectiveness. LTP involves diverse changes, including creating new synapses, enhancing previous synapses, and building new dendritic branches and spines (Breedlove & Watson, 2020).

To learn more, watch the Khan Academy video Long Term Potentiation and Synaptic Plasticity.

Glossary

40-Hz rhythm: gamma rhythm hypothesized to be associated with feature binding (linking an apple's color to its shape) and attributed to the neocortex and thalamocortical neurons.

acetylcholine: an amine neurotransmitter that binds to nicotinic and muscarinic ACh receptors.

acetylcholine esterase (AChE): the enzyme that deactivates ACh.

AChE-R: an abnormal form of acetylcholine esterase (AChE) may render dendrites with acetylcholine receptors more excitable when stressed.

action potential: a propagated electrical signal that usually starts at a neuron’s axon hillock and travels to presynaptic axon terminals.

adenylate cyclase: at a metabotropic receptor, an enzyme that transforms ATP into the second messenger cyclic AMP.

afferent: a neuron that transmits sensory information towards the central nervous system or from one region to another.

allocortex: cortex that contains three or four layers and is comprised of the olfactory system and hippocampus.

all-or-none law: once an action potential is triggered in an axon, it is propagated, without decrement, to the end of the axon. The amplitude of the action potential is unrelated to the intensity of the stimulus that triggers it.

alpha blocking: arousal and specific forms of cognitive activity may reduce alpha amplitude or eliminate it entirely while increasing EEG power in the beta range.

alpha rhythm: 8-12-Hz activity that depends on the interaction between rhythmic burst firing by a subset of thalamocortical (TC) neurons that are linked by gap junctions and rhythmic inhibition by widely distributed reticular nucleus neurons. Researchers have correlated the alpha rhythm with "relaxed wakefulness." Alpha is the dominant rhythm in adults and is located posteriorly. The alpha rhythm may be divided into alpha 1 (8-10 Hz) and alpha 2 (10-12 Hz).

alpha spindles: regular bursts of alpha activity.

alpha-subunit: a subunit of a G protein associated with the neuron membrane that breaks away to activate enzymes within the neuron when a ligand binds to a metabotropic receptor.

amino acid neurotransmitters: the oldest family of transmitters. These molecules bind to ionotropic and metabotropic receptors, so they transmit information and modulate neuronal activity. In the brain, most synaptic communication is accomplished by glutamate (generally excitatory) and GABA (generally inhibitory).

AMPA (glutamate) receptors: ionotropic receptors which open sodium channels, depolarize the neuron's membrane (producing an EPSP), and dislodge a Mg+ ion that blocks an adjacent NMDA (glutamate) receptor's calcium channel. AMPA receptors are responsible for most activity at glutamatergic synapses.

amplitude: the energy or power contained within the EEG signal measured in microvolts or picowatts.

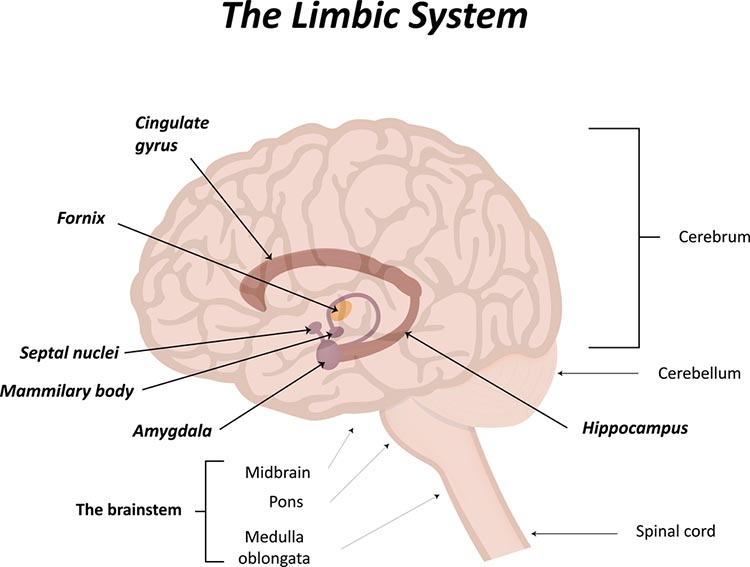

amygdala: the limbic system structure that participates in evaluating whether stimuli are salient (rewarding or threatening), establishing unconscious emotional memories, learning conditioned emotional responses, and producing anxiety and fear responses.

anion: a negative ion, for example, chloride (Cl-).

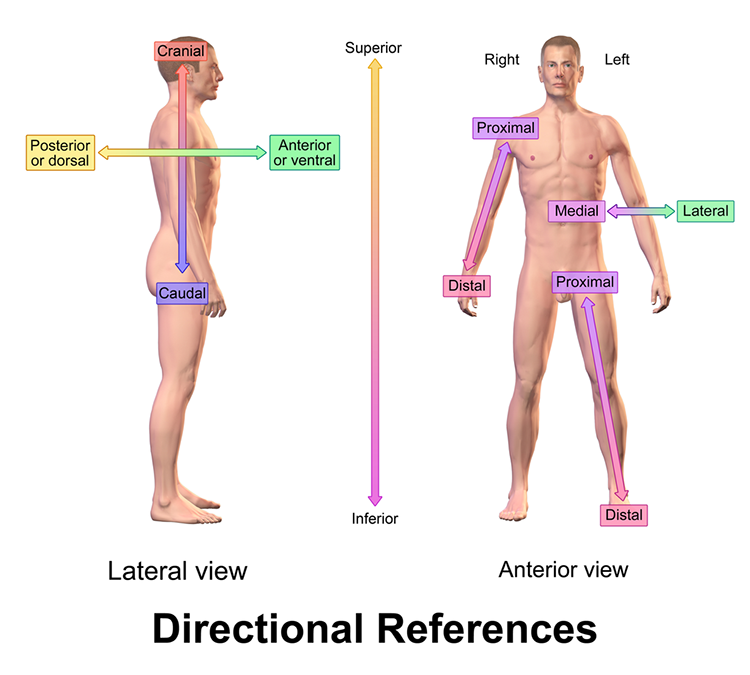

anterior: near or toward the front of the head, for example, the anterior cingulate.

anterior cingulate: a division of the prefrontal cortex that plays a vital role in attention and is activated during working memory. It mediates emotional and physical pain, and has cognitive (dorsal anterior cingulate) and affective (ventral anterior cingulate) conflict-monitoring components.

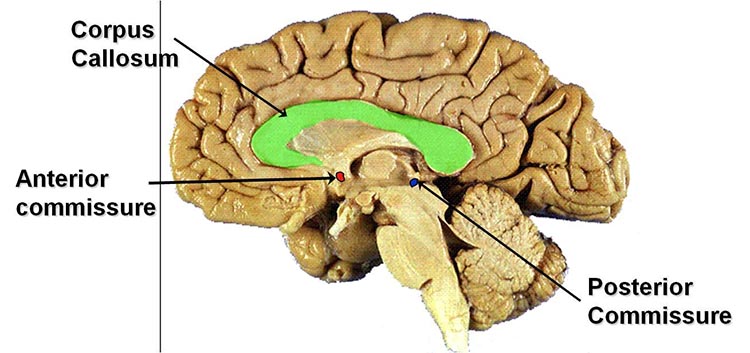

anterior commissure: a bundle of nerve fibers that crosses the midline and connects the left and right temporal lobes and the hippocampus and amygdala.

apical dendrite: a dendrite that arises from the top of the pyramid and extends vertically to layer 1 of the neocortex.

arousal: a process that combines alertness and wakefulness, produced by at least five neurotransmitters, including acetylcholine, histamine, hypocretin, norepinephrine, and serotonin.

aspinous (smooth) neurons: neurons without dendritic spines that are believed to be inhibitory.

astrocytes: star-shaped glial cells that communicate with and support neurons and help determine whether synapses will form.

asynchronous waves: neurons depolarize and hyperpolarize independently.

ATP: energy source for a neuron’s sodium-potassium transporters.

autoreceptors: metabotropic receptors that can be located on the membrane of any part of a neuron. They detect neurotransmitters the neuron releases, generate IPSPs that inhibit the neuron from reaching the excitation threshold, and regulate internal processes like transmitter synthesis and release through the second messenger system.

axoaxonic synapses: junctions between two axons that do not affect the generation of an action potential, only the amount of neurotransmitter distributed.

axodendritic synapses: junctions between axons and dendrites that determine whether the axon hillock will initiate an action potential.

axon: long, cylindrical structures that convey information from the soma to the terminal buttons. An axon also transports molecules in both directions along the outer surface of protein bundles called microtubules.

axon hillock: a swelling in the cell body where a neuron integrates the messages it has received from other neurons and decides whether to fire an action potential.

axon terminal: buds located on the ends of axon branches that form synapses and release neurochemicals to other neurons.

axonal varicosity: a swelling in an axon wall that releases neurotransmitters through the wall via volume transmission.

axoplasmic transport: the movement of molecules in both directions along the outer surface of protein bundles called microtubules.

basal dendrite: a dendrite that horizontally branches out from the 30 μm base of the pyramid through the layer where the neuron resides.

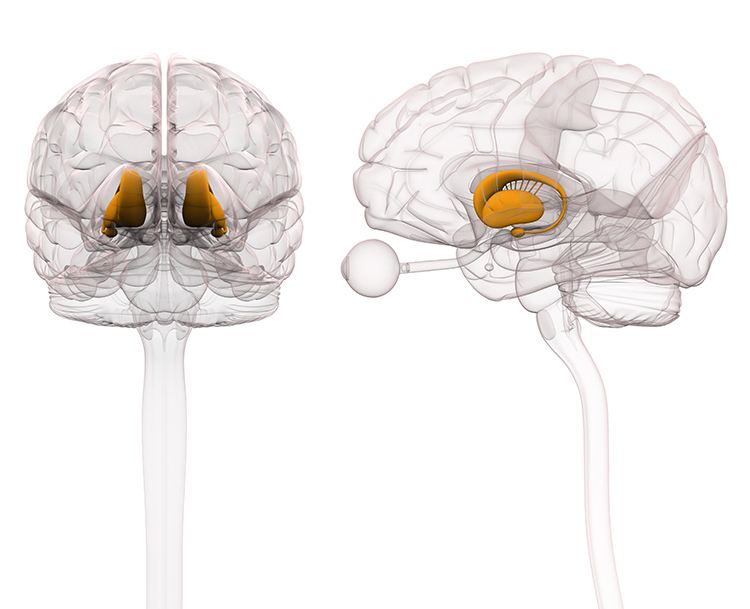

basal ganglia: forebrain structures consisting of an egg-shaped nucleus that contains the putamen and globus pallidus and a tail-shaped structure called the caudate, which together are responsible for the production of movement. The basal ganglia have also been implicated in obsessive-compulsive disorder, Parkinson’s disease, and Huntington’s chorea.

beta rhythm: 12-38-Hz activity associated with arousal and attention generated by brainstem mesencephalic reticular stimulation that depolarizes neurons in both the thalamus and cortex. The beta rhythm can be divided into multiple ranges: beta 1 (12-15 Hz), beta 2 (15-18 Hz), beta 3 (18-25 Hz), and beta 4 (25-38 Hz).

bilateral synchronous slow waves: a pathological sign observed in drowsy children. When detected in alert adults, intermittent bursts of high amplitude slow waves may signify gray matter lesions in deep midline structures.

cation: positive ion, for example, sodium (Na+).

caudal: away from the front of the head.

cell body or soma: part of a neuron that contains machinery for cell life processes and receives and integrates EPSPs and IPSPs from axons generated by axosomatic synapses (junctions between axons and somas). The cell body of a typical neuron is 20 μm in diameter, and its spherical nucleus, which contains chromosomes comprised of DNA, is 5-10 μm across.

central nucleus of the amygdala: nucleus that orchestrates the nervous system's response to important stimuli by activating circuits in the brainstem (autonomic arousal) and the basal ganglia and periaqueductal gray (defensive behavior).

cerebral cortex: the layer of gray matter that covers the cerebral hemispheres. The cerebral cortex consists of gray matter and white matter.

chemical synapses: junctions between neurons that transmit molecules across gaps of less than 300 angstroms. Neurons use chemical synapses to produce short-duration (millisecond) and long-duration (seconds to hours) changes in the nervous system. Chemical synapses are capable of more extensive communication and initiating more diverse and long-lasting changes than electrical synapses.

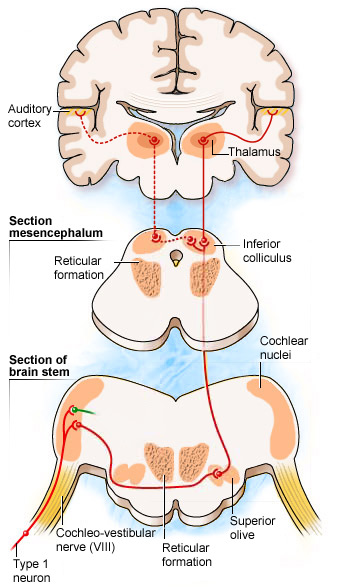

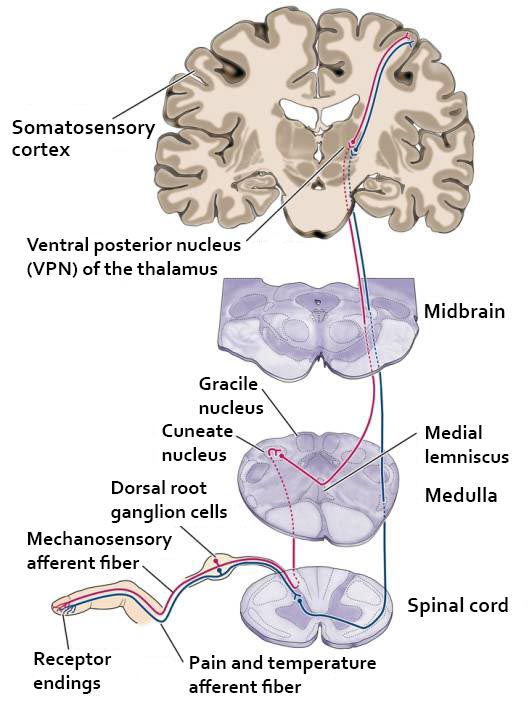

classical routes for EEG activation: specific sensory pathways like the visual (retina to the visual cortex), auditory (cochlea to the auditory cortex), and somatosensory (chemoreceptors and mechanoreceptors to the somatosensory cortex) systems. Increased transmission of information through these pathways desynchronizes EEG activity in the cortical regions to which these afferent neurons project, as specialized circuits of neurons independently process this information.

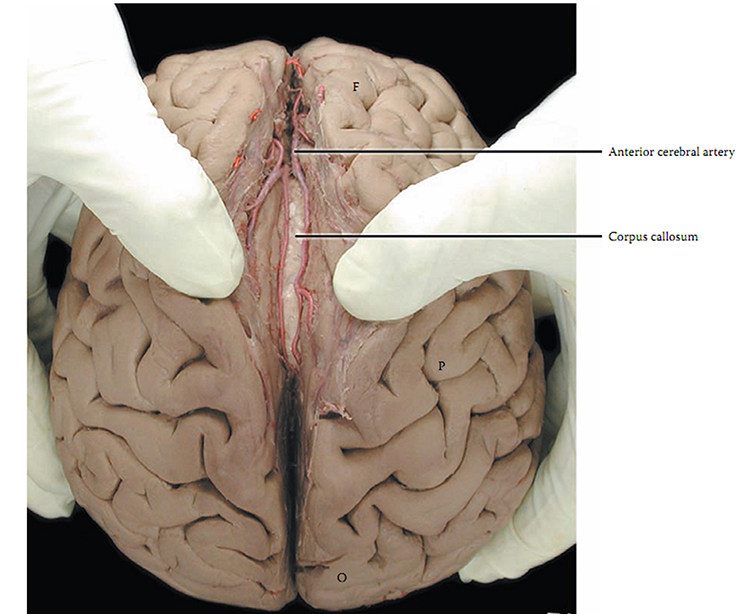

commissures: axon tracts. The left and right hemispheres communicate using the corpus callosum, anterior commissure, and posterior commissure.

complex: a sequence of waves.

COMT: a degrading enzyme that only targets the catecholamines dopamine and norepinephrine.

contingent negative variation (CNV): a steady, negative shift in potential (15 microvolts in young adults) detected at the vertex. This slow cortical potential may reflect expectancy, motivation, intention to act, or attention. The CNV appears 200-400 ms after a warning signal (S1), peaks within 400-900 ms, and sharply declines after a second stimulus that requires the performance of a response (S2).

continuous irregular delta: slow waves produced by white matter lesions seen in disorders like multiple sclerosis.

contralateral: structures that are located on opposite sides of the body. For example, neurons in the left primary motor cortex control muscles on the right side of the body.

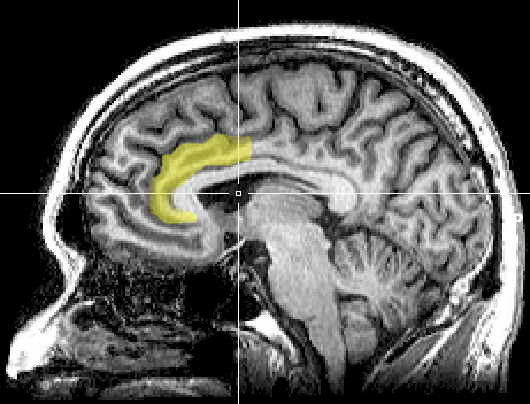

corpus callosum: the largest commissure that connects the left and right frontal, parietal, and occipital lobes.

corticothalamic network: a unified network that generates diverse types of brain rhythms grouped by slow cortical oscillations.

cyclic AMP: a second messenger that moves about the neuron, activating other enzymes. Protein kinase A, which controls the excitability of ion channels, is a crucial enzyme target of cyclic AMP. Cyclic AMP also travels to the nucleus, where it can regulate gene expression.

Dale's principle: incorrect view that a neuron can only release one neurotransmitter. They often release two to four.

delta rhythm: 0.05-3 Hz oscillations generated by thalamocortical neurons during stage 3 sleep.

dendrite: a branched structure designed to receive messages from other neurons via axodendritic synapses (junctions between axons and dendrites), determining whether the axon hillock will initiate an action potential.

dendritic spines: protrusions on the dendrite shaft where axons typically form axodendritic synapses.

dendrodendritic synapses: junctions between dendrites that communicate chemically across synapses and electrically across gap junctions.

depolarization: to make the membrane potential less negative by making the inside of the neuron less negative with respect to its outside.

diffusion: the distribution of molecules from areas of high concentration to low concentration.

diphasic wave: a wave that contains both a negative and positive deflection from the baseline.

dipole: the electrical field generated between the sink (where current enters the neuron ) and the source (place at the other end of the neuron where current leaves), which may be located anywhere along the dendrite.

dominant frequency: the EEG frequency with the most significant amplitude.

dopamine: a monoamine neurotransmitter exerts its postsynaptic effects on at least six receptors linked to G proteins. This means that dopamine functions as a neuromodulator. The two families include D1 (D1 and D5) and D2 (D2A, D2B, D3, and D4).

dorsal: toward the upper back or head.

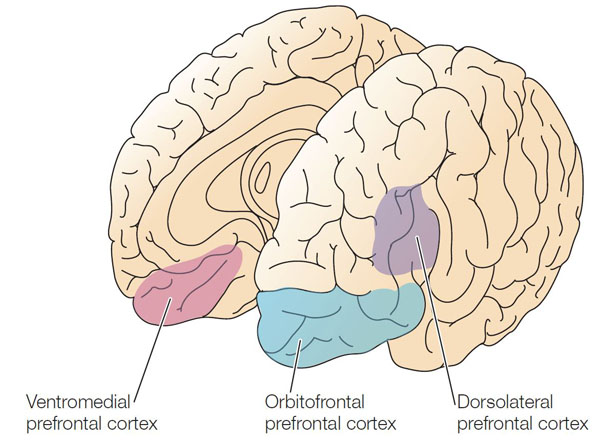

dorsolateral prefrontal cortex: the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is concerned with approach behavior and positive affect. It helps us select positive goals and organizes and implements behavior to achieve these goals. The right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex organizes withdrawal-related behavior and negative affect and mediates threat-related vigilance. It plays a role in working memory for object location.

D-serine: a neurotransmitter that binds to the glycine site on the NMDA receptor to trigger calcium entry into a dendritic spine when glutamate binds to its site, resulting in a large, prolonged increase in intracellular calcium.

dual-action antidepressants: medications that activate 5-HT1 receptors to produce antidepressant and anxiolytic effects, while they blockade 5-HT2 (agitation, restlessness, and sexual dysfunction) and 5-HT3 (nausea, headache, and vomiting) receptors to minimize their side effects.

EEG activity: single wave or successive waves.

EEG power: the signal energy in the EEG spectrum. Most EEG power falls within the 0-20 Hz frequency range. EEG power is measured in microvolts or picowatts.

efferent: motoneuron that transmits information towards the periphery.

electrical synapse: symmetrical synapse where neurons communicate information bidirectionally across gap junctions between adjacent membranes using ions. Transmission across electrical synapses is instantaneous, compared with the 10-ms or longer delay in chemical synapses. The rapid information transmission that characterizes electrical synapses enables large circuits of distant neurons to synchronize their activity and simultaneously fire.

electroencephalogram (EEG): the voltage difference between at least two electrodes, where at least one electrode is located on the scalp or inside the brain. The EEG is a recording of EPSPs and IPSPs that occur primarily in dendrites in pyramidal cells located in macrocolumns, several millimeters in diameter, in the upper cortical layers.

electrostatic pressure: the attractive or repulsive force between ions that moves them from one region to another.

entorhinal cortex: a structure located in the caudal region of the temporal lobe and receives pre-processed sensory information from all modalities and reports on cognitive operations. The entorhinal cortex provides the main input to the hippocampus, and is involved in memory consolidation, spatial localization, and provides input into the septohippocampal system that may generate the 4-7 Hz theta rhythm.

enzymatic deactivation: the process in which an enzyme breaks a neurotransmitter apart into inactive fragments. For example, acetylcholine transmission is ended by the enzyme acetylcholine esterase (AChE). Deactivating enzymes located in the synaptic cleft degrade a neurotransmitter molecule when it detaches from its binding site.

evoked potential: an event-related potential (ERP) elicited by external sensory stimuli (auditory, olfactory, somatosensory, and visual). An evoked potential has a negative peak at 80-90 ms and a positive peak around 170 ms following stimulus onset. The orienting response ("What is it?") is a sensory ERP. The N1-P2 complex in the auditory cortex of the temporal cortex reveals whether an uncommunicative person can hear a stimulus.

excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP): a brief positive shift in a postsynaptic neuron's potential produced when neurotransmitters bind to receptors and cause positive sodium ions to enter the cell. An EPSP pushes the neuron towards the threshold of excitation when it can initiate an action potential.

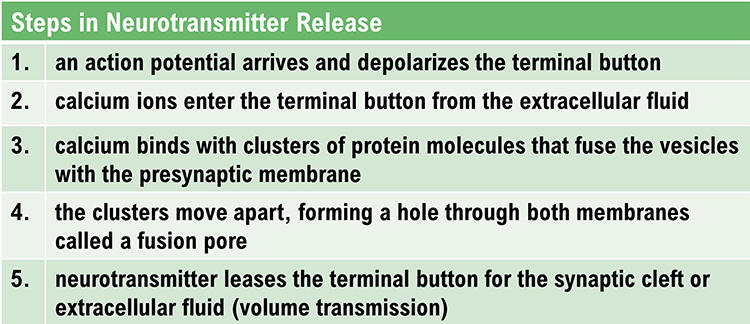

exocytosis: the process of neurotransmitter release. When an action potential arrives and depolarizes the terminal button, calcium ions enter the terminal button from the extracellular fluid. Calcium binds with clusters of protein molecules that connect the vesicles to the presynaptic membrane. The clusters move apart, forming a hole through both membranes called a fusion pore, and the neurotransmitter leaves the terminal button for the synaptic cleft or extracellular fluid.

exogenous ERP: an event-related potential (ERP) elicited by external sensory stimuli (auditory, olfactory, somatosensory, and visual).

explicit learning: behavioral changes that occur with our conscious awareness that require processing by the hippocampus.

extracellular dipole layers: macrocolumns of pyramidal cells, which lie parallel to the surface of the cortex, send opposite charges towards the surface and the deepest of the 5-7 layers of cortical neurons.

extracellular fluid: the fluid surrounding a neuron.

fast cortical potentials: EEG rhythms that range from 0.5 Hz-100 Hz. The main frequency ranges include delta, theta, alpha, sensorimotor rhythm, and beta.

feature binding: the process of linking information to perceptual objects (linking an apple's color to its shape) that may involve the 40-Hz rhythm.

fissures: deep grooves, for example, the lateral fissure.

focal waves: EEG waves that are detected within a limited area of the scalp, cerebral cortex, or brain.

frequency: the number of cycles completed each second expressed in hertz (Hz).

frequency synchrony: when identical EEG frequencies are detected at two or more electrode sites. For example, 12 Hz may be simultaneously detected at O1-A1 and O2-A2.

frontal lobes: the most anterior cortical lobes of the brain that are divided into the motor cortex, premotor cortex, and prefrontal cortex.

fusion pore: a hole through a vesicle and presynaptic membrane that allows neurotransmitter to leave the terminal button for the synaptic cleft or extracellular fluid.

G protein: a protein located inside a neuron’s membrane next to a metabotropic receptor that is activated when the receptor binds a ligand. An alpha-subunit of the G protein then breaks away to perform actions within the cell.

GABA: an amino acid that is often inhibitory and that may be the most important inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain. There are several types of GABA receptors, each of which produces inhibition differently.

gamma rhythm: EEG activity frequencies above 30 or 35 Hz. Frequencies from 25-70 Hz are called low gamma, while those above 70 Hz represent high gamma.

gap junction: narrow space between two cells bridged by connexons (protein channels) that allow ions to travel between them rapidly.

generalized asynchronous slow waves: waves that are seen in sleepy children and those with elevated temperatures. These waves may indicate degenerative disease, dementia, encephalopathy, head injury, high fever, migraine, and Parkinson's disease in adults.

glial cells: nonneural cells that guide, insulate, and repair neurons and provide structural, nutritional, and information-processing support. Glial cells generate slow cortical potentials (SCPs). Glial cells include astrocytes, microglia, oligodendrocytes, radial glial cells, and Schwann cells.

glutamate: an amino acid that is often excitatory and that may be the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain. Its receptors are found on the surface of almost all neurons. There are at least 13 different receptors for glutamate, 5 ionotropic and 8 metabotropic. Most presynaptic neurons in the brain excite postsynaptic neurons via ionotropic glutamate receptors in the postsynaptic membrane. Metabotropic glutamate receptors may play a regulatory function, either augmenting or suppressing the activation of ionotropic glutamate receptors.

glycine: an amino acid that is often inhibitory and has a binding site on the NMDA receptor.

gray matter: brain tissue that looks grayish brown and comprises cell bodies, dendrites, unmyelinated axons, glial cells, and capillaries.

gyrus: ridge of cortex demarcated by sulci or fissures, for example, the precentral gyrus.

hertz (Hz): the unit of frequency, an abbreviation for cycles per second.

hippocampus: a limbic structure located in the medial temporal lobe involved in 4-7 Hz theta activity, control of the endocrine system’s response to stressors, formation of explicit memories, and navigation. Cortisol binding to this structure disrupts these functions, interferes with creating new neurons, and harms and kills hippocampal neurons.

hubs: highly centralized nodes through which other node pairs communicate; hubs allow efficient communication.

hyperpolarize: a negative shift in membrane potential (the inside becomes more negative with respect to the outside) due to the loss of positive ions or gain of negative ions.

inhibitory postsynaptic potential (IPSP): a brief negative shift in a postsynaptic neuron's potential produced when cations like potassium leave a neuron or anions (negative ions) like chloride enter a neuron, which hyperpolarize the cell. An IPSP pushes the neuron away from its excitation threshold.

integration: the addition of EPSPs and IPSPs at the axon hillock. Neurons sum EPSPs and IPSPs over their surface in spatial integration and over milliseconds in temporal integration to raise the membrane from its resting potential to the excitation threshold. EPSPs and IPSPs last from 15-200 ms, while action potentials occur in 1-2 ms.

interneurons: neurons that receive input from and distribute output to other neurons. They have short processes and are confined to the central nervous system. They provide the integration required for decisions, learning and memory, perception, planning, and movement.

intracellular fluid: the watery cytoplasm contained within a neuron.

ion: a charged atom or molecule with a positive or negative charge. Positive ions are called cations, and negative ions are called anions.

ionotropic receptor: receptor protein that contains a binding site for a ligand and an ion channel that opens when the neurotransmitter attaches to this site.

ipsilateral: structures that are located on the same side of the body. For example, the left olfactory bulb distributes axons to the left hemisphere.

irregular waves: successive waves that constantly alter their shape and duration.

kappa rhythm: bursts of alpha or theta and is detected over the temporal lobes of subjects during cognitive activity.

lambda waves: saw-toothed transient waves from 20-50 μV in amplitude and 100-250 ms in duration detected over the occipital cortex during wakefulness. These positive deflections are time-locked to saccadic movements and observed during visual scanning, as during reading.

lateral: to the side, away from the center, as in the lateral geniculate nucleus.

lateral nucleus of the amygdala: a nucleus that processes sensory information and distributes it throughout the amygdala.

lateralized waves: waves that are primarily detected on one side of the scalp and that may indicate pathology.

Layers I-III: cortical layers that receive corticocortical afferent fibers that connect the left and right hemispheres.

Layer III: the cortical layer that is the primary source of corticocortical efferent fibers.

Layer IV: the cortical layer that is the primary destination of thalamocortical afferents and intra-hemispheric corticocortical afferents.

Layer V: the cortical layer that is the primary origin of efferent fibers that target subcortical structures that have motor functions.

Layer VI: the cortical layer that projects corticothalamic efferent fibers to the thalamus, which, together with the thalamocortical afferents, creates a dynamic and reciprocal relationship between these two structures.

left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex: the division of the prefrontal cortex concerned with approach behavior and positive affect. It helps us select positive goals and organizes and implements behavior to achieve these goals.

local field potential: the aggregate effect of the firing of the interconnected pyramidal neurons within the cortical columns plus additional mechanisms like glial cell modulation of the cortical electrical gradient.

local synchrony: synchrony that occurs when high-amplitude EEG signals are produced by the coordinated firing of cortical neurons.

localized slow waves: waves that may indicate a transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke, migraine, mild head injury, or tumors above the tentorium. Deep lesions result in bilateral or unilateral delta.

locus coeruleus: the noradrenergic branch of the ascending reticular activating system, which is responsible for vigilance. Subnormal norepinephrine transmission may contribute to ADHD.

long-latency potentials: potentials that have extended latencies following stimulus onset, for example, P300 and N400 ERPs.

long-term depression (LTD): a persistent decrease in synaptic strength following low-frequency stimulation.

long-term potentiation (LTP): a persistent increase in synaptic strength following high-frequency stimulation.

macrocolumns: circuits of cortical pyramidal neurons several millimeters in diameter that create extracellular dipole layers parallel to the surface of the cortex that send opposite charges towards the surface and the deepest of the 5-7 layers of cortical neurons. Since the pyramidal neurons are all aligned with the cortical surface, the postsynaptic potentials at cells within the same macrocolumn add together. This summation occurs because they share the same charge and the macrocolumns fire synchronously.

medial: toward the center of the body, away from the side. For example, the medial geniculate nucleus.

medial prefrontal cortex: the division of the prefrontal cortex that integrates cognitive-affective information and helps control the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis during emotional stress.

membrane potential: a neuron’s electrical charge created by a difference in ion distribution within and outside the neuron. A typical resting potential is about -70 mV (thousandths of a volt), since the inside of a resting axon is more negatively charged than the outside.

mesocortical neurons: dopaminergic neurons that project from the ventral tegmental area of the midbrain to the prefrontal cortex and excite prefrontal cortical neurons that control working memory, planning, and strategy preparation for problem-solving. Underactivity in this pathway is associated with the negative symptoms of schizophrenia-like attentional deficits.

metabotropic receptors: include all G protein-linked receptors located on neurons, including autoreceptors. Neurotransmitters that bind to G protein-linked receptors are often called neuromodulators. Metabotropic receptors, which indirectly control the cell's operations, expend energy, and produce slower, longer lasting, and more diverse changes than ionotropic receptors. Their effects can last several seconds, instead of milliseconds, because of the long-lived activity of G proteins and cyclic AMP.